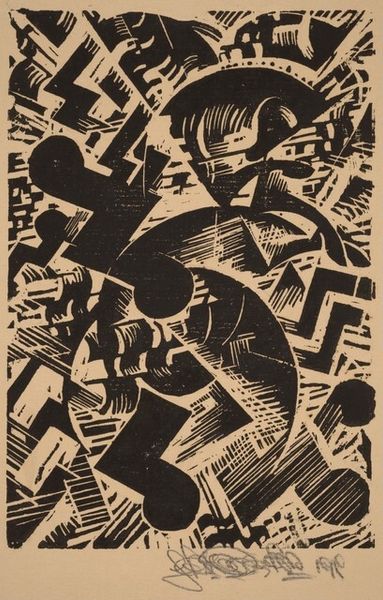

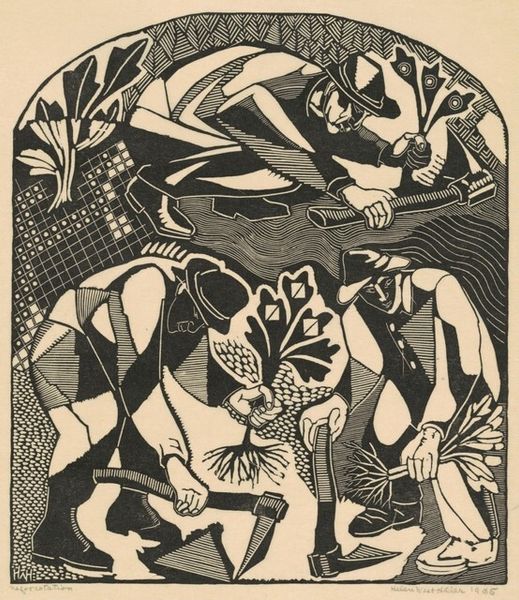

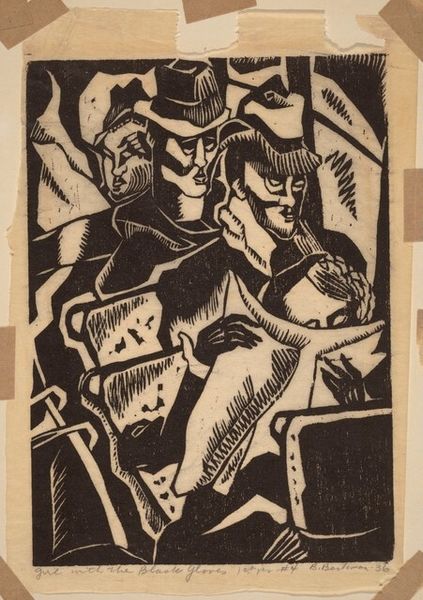

print, linocut

#

linocut

# print

#

linocut

#

figuration

#

abstract

#

geometric

#

modernism

Dimensions: plate: 20 x 15 cm (7 7/8 x 5 7/8 in.) sheet: 32.8 x 25.1 cm (12 15/16 x 9 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Sue Fuller's "Clown," a linocut print from 1945. Editor: It's quite striking. The harsh lines and clashing colours evoke a chaotic feeling—not exactly the jovial image the title brings to mind. Curator: Exactly, and that tension is central to understanding it. Think about the context, 1945, the end of World War II. What did the figure of a "clown" represent in those years? Could it symbolize the shattered illusions of victory? The anxiety bubbling beneath a surface of forced normalcy? Editor: Perhaps, but let’s focus on how this was constructed. Looking at the linocut, you see the deliberate carving marks, the way Fuller manipulated the material to achieve this expression. It’s labor-intensive, physical work, carving away at the block, creating areas of high contrast. Curator: Definitely. And consider Fuller’s broader body of work. She was part of a generation grappling with modernist aesthetics, abstracting the figure, pushing against traditional representation. This isn't a happy-go-lucky clown; it’s a deconstruction, a dismantling. Editor: It’s fascinating how the abstract, geometric background clashes with the figuration of the clown. There is definitely a tension here, maybe this expresses more the artist´s frustration or some social uneasiness of that moment, than an amusement act. Curator: And the colours! The jarring green, yellow and red...they scream, rather than sing. This evokes for me questions about societal performances, the roles we play. A clown, by profession, hides behind a mask, forcing joy even amid potential personal turmoil. Editor: Yes, these are harsh tones and shapes… this almost has the feeling of brutalist architecture translated to print. There’s a sense of industrial precision despite being a handmade print, something grounded and firm. Curator: "Clown" becomes a lens through which we can interrogate themes of identity, forced happiness, and the disillusionment that can follow moments of grand historical change. It refuses to be simply decorative. Editor: Well said. Analyzing the material execution of the work enhances our understanding of these complex concepts. Seeing the intentional marks left behind provides evidence of this era, creating something that holds power beyond its aesthetic design. Curator: Precisely. It invites a deeper conversation that connects artistic practice to broader social and political currents. Editor: I concur; there is a disquieting energy when process and concept combine to deliver a unique image from a troubled moment in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.