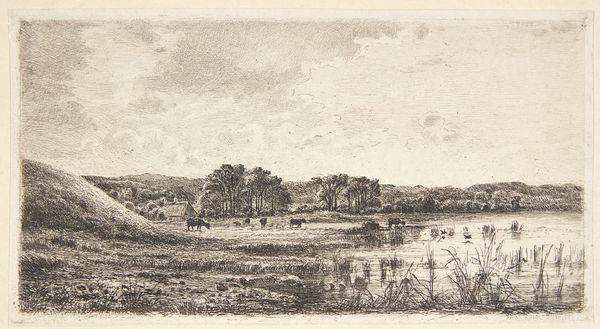

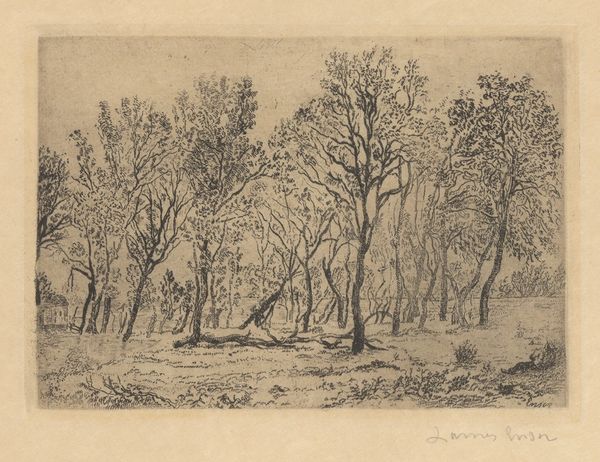

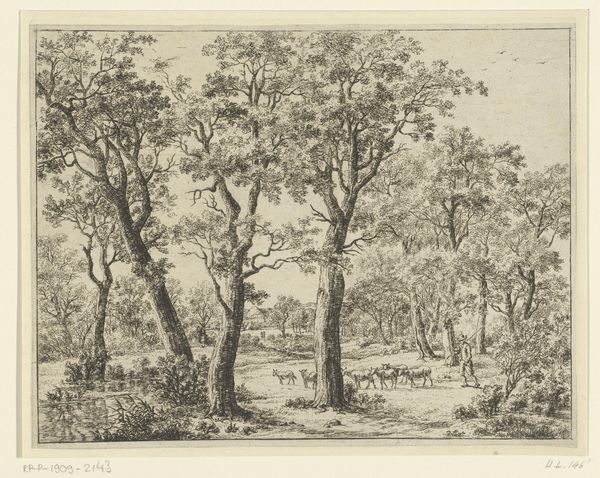

Landschap met herder en kudde schapen 1845 - 1925

0:00

0:00

juliusjacobusvandesandebakhuyzen

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, here we have "Landschap met herder en kudde schapen"—"Landscape with Shepherd and Flock of Sheep"—a drawing made with pen, dating somewhere between 1845 and 1925. It's housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, attributed to Julius Jacobus van de Sande Bakhuyzen. Editor: Sheep, you say? Hmm, it’s funny how sheep always manage to look like worried cotton balls, aren't they? There's something rather bleak and exposed about this little scene; the scraggly trees look a bit desperate for a friend. Curator: Well, Bakhuyzen, drawing upon both Realism and Romanticism, taps into agrarian life but doesn't necessarily sugarcoat it. This wasn't about pastoral fantasy. Consider the context: shifting land ownership, rural poverty... Bakhuyzen witnessed it firsthand. We can frame this work through a lens of socio-economic commentary, noting how land use impacted those who lived off it. Editor: Yes, but it still comes back to that overall feeling of melancholic open space, right? The horizon line is low; that just increases the sense of isolation and expanse. Technically, those quick pen strokes communicate the coarse texture of the landscape. You can practically feel the wind. It makes me think about personal displacement more than broad socioeconomics. The shepherd feels a long way from home. Curator: Personal displacement certainly plays a role, intersecting with the widespread shifts within agricultural communities. What does it mean to capture such common subjects, during that epoch, when those familiar rural environments are changing, eroding the traditional pastoral lifestyle? Editor: It means he bottled some pure Dutch countryside angst! And then scribbled all over the label. It looks deceptively casual but its heavy atmosphere communicates its intent in volumes. You sense it and recognize the universal pangs, rather than consciously considering agrarian shifts and historical contexts. It cuts through like loneliness. Curator: The point isn't to divorce the emotional response, but to realize its context— to appreciate how intertwined our feelings are with the systemic pressures that inform our experience, in turn. A work like this allows for dialogue across time, theory, and even lived experiences regarding land and belonging. Editor: I guess that's it in the end—belonging. Feeling rooted and safe is everyone's basic want. Whatever way you interpret the artwork, whether politically or intuitively, its effect remains consistent. This reminds us about how tender that core need really is, and that even art as simple as a pencil sketch can hold such power!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.