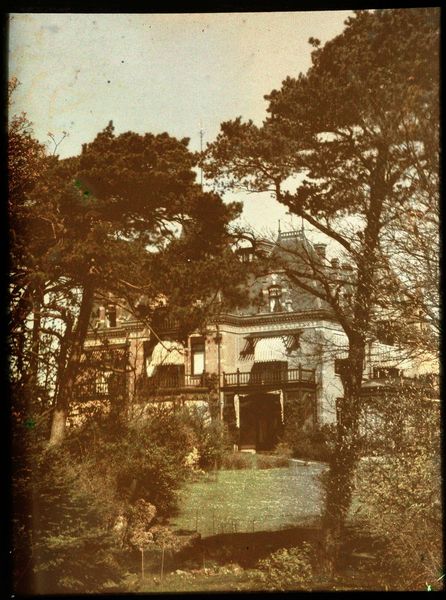

Gezicht op een boerderij, met links een schuur of bijgebouw 1907 - 1930

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I’m struck by the light. It feels like a fleeting moment, almost dreamlike. Editor: Indeed. We’re looking at “Gezicht op een boerderij, met links een schuur of bijgebouw,” which translates to "View of a Farmhouse, with a Barn or Outbuilding on the Left", a piece attributed to Adolphe Burdet and created sometime between 1907 and 1930. What captivates me is the rendering. We can almost see how it was made through photography. Curator: Absolutely. And what does this rendering tell us? For me, this embodies a feeling of isolation and rurality in early 20th-century. Editor: I see it too, and it speaks to something deeper – the relationship between humans and their environment. The way that it depicts the home alongside agriculture is interesting, and the architecture plays a role. Consider that while the building might look aged, with its vine covering, the shuttered windows are a much more calculated touch, as are the perfectly laid brick roof tiles. Curator: Right. Those details do give a new meaning to how people choose to live amongst one another in the modern age. Did they decide to cultivate and expand nature’s role within domestic life? Or attempt to tame the land through material means? Editor: Perhaps a blend of both. Labor is certainly central to any reading here. Note the lack of any individuals inhabiting this world: there is work being done, yet only a record of the people performing it remains, with its photographic capture serving to emphasize the effort taken. This also invites a bit of analysis concerning what Burdet wanted the focus to be. Curator: I agree, the focus here raises complex questions of class and power relations within that specific socio-political context. Perhaps the absent figure gestures toward class, towards issues facing women and laborers in this specific geography. Editor: And these class dynamics often have an undeniable material manifestation – what is worth keeping and investing in can signal social relations in that era. I wonder then if our task remains in attempting to connect an individual artist’s vision of production within early-century society and social concerns. Curator: Ultimately, this image prompts a necessary dialogue about these systems that affect not just the landscapes, but those who cultivate it, then and now. Editor: I leave contemplating this idea, this question of balance that has long fueled cultural imaginings about life.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.