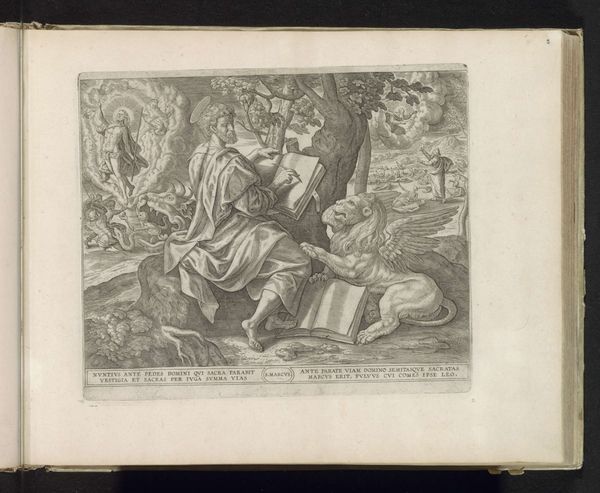

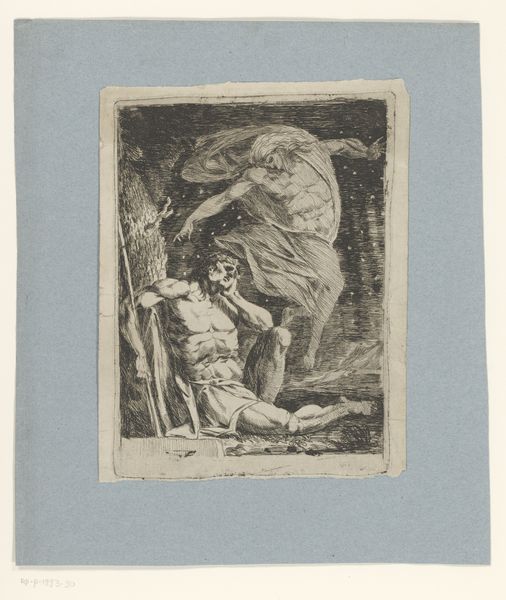

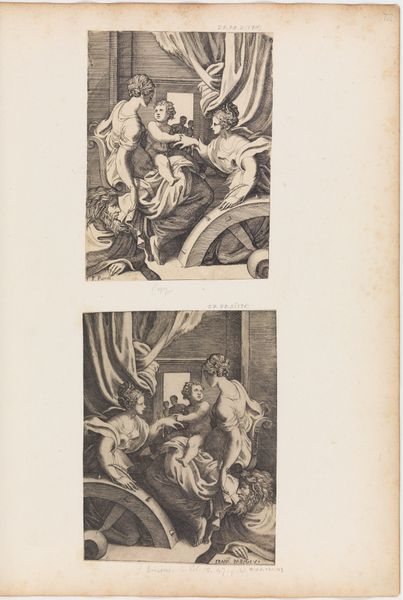

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio’s "Diogenes," a print made sometime between 1500 and 1565, now residing here at the Met. I’m struck by the figure's isolation, that bare setting; the details around him almost feel like clues. What's your reading of the symbolism in this piece? Curator: The starkness indeed underscores the figure's deliberate detachment. Notice the rooster – a symbol of vigilance but also pride, placed in the upper right – is there a subtle commentary on Diogenes's own perceived arrogance, perhaps? Editor: I hadn’t thought of the rooster that way, more of a barnyard detail! The open book in the lower left, though—it has a geometric figure in it. Curator: Yes, precisely. Geometry here resonates with the rational world, the very systems Diogenes rejects in favour of natural law and self-sufficiency. He points to it almost dismissively, contrasting human constructs with something simpler, perhaps more authentic represented by the sphere he is holding. Ask yourself: is that a miniature cosmos? Editor: So, is Caraglio positioning Diogenes as a rebel against intellectual tradition, or something more complex? Curator: He’s tapping into a long tradition of Diogenes as both admirable ascetic and social irritant. This is a figure who dared to challenge convention. The lamp he holds isn’t just for light but for revealing, for "finding an honest man," as the old stories tell. What does it tell us about Caraglio and his own time, that such a figure should be compelling? Editor: Interesting! The way symbols are used really complicates the message. I will certainly rethink my understanding of prints from that era. Curator: Visual symbols were rarely simple statements, instead opening avenues into a rich world of ideas and ideals we keep relearning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.