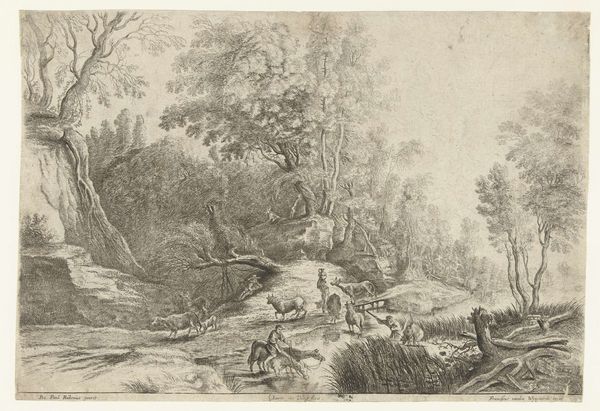

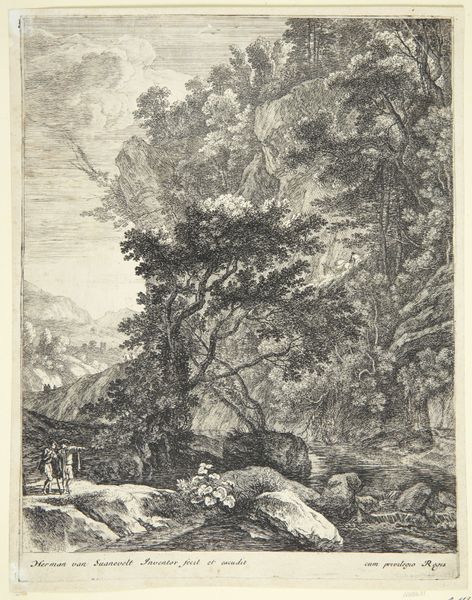

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

realism

Dimensions: 182 mm (height) x 275 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: I’m instantly drawn to the gentle quality of light in this scene—it's almost like a hazy summer afternoon filtering through the trees. There’s such a stillness to it. Editor: This is “Heste og køer ved et vandingssted,” which roughly translates to "Horses and Cattle by a Watering Place," an etching and print attributed to Lucas van Uden. His dates range from 1595 to 1673, so it gives us a wide window into when this work may have been produced, situating it squarely in the Dutch Golden Age. Curator: Yes, that era really knew how to capture the everyday! The animals and figures seem so at ease in their surroundings. The details, especially considering it’s a print, are captivating—the way the light dances on the water is superb. Editor: And there is nothing unintentional in that. Van Uden clearly reflects the social structures and class relations within this pastoral setting. Land ownership, labor, and the commodification of nature were very important. The livestock are signs of economic stability, representing agricultural wealth during that period. Curator: That’s a really interesting point—how these images reflected more than just pastoral charm. I always find myself pondering how many moments like this the artist witnessed, what caught his attention, and what did this Watering Place look like through his own subjective reality? Editor: The "subjective reality" you mention reminds us of how representations of labor in the Dutch Golden Age were not merely objective recordings. Often the narratives omit the experiences of the working class, glossing over the difficult realities of agrarian labor, even while valorizing the pastoral lifestyle. Curator: I suppose my emotional reaction to that idyllic serenity is challenged. Perhaps I’m too quick to idealize something I didn't actually live through! Editor: That impulse to romanticize such historical periods is something we must continue to examine critically. This tension—between idyllic representation and lived realities—makes these works, especially within landscape, continuously relevant for dialogue. Curator: Right—it makes me reconsider my initial impressions and look beyond the immediately pleasing aesthetic. I feel refocused! Editor: It is so vital for contemporary viewers to engage with artworks of the past by drawing connections between artistic conventions, historical context, and our present-day socio-political landscape. It makes this image, and many like it, resonate far beyond its initial impression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.