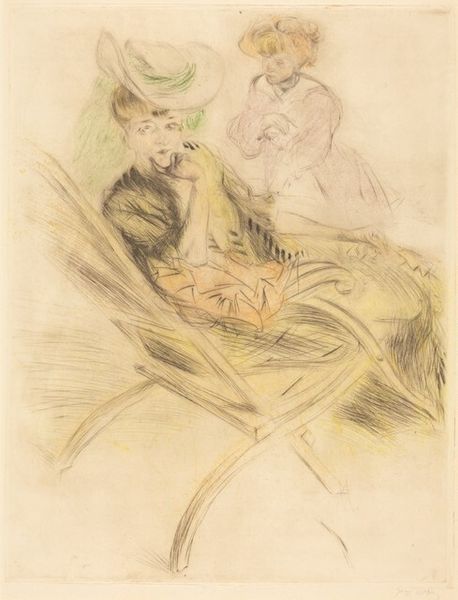

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

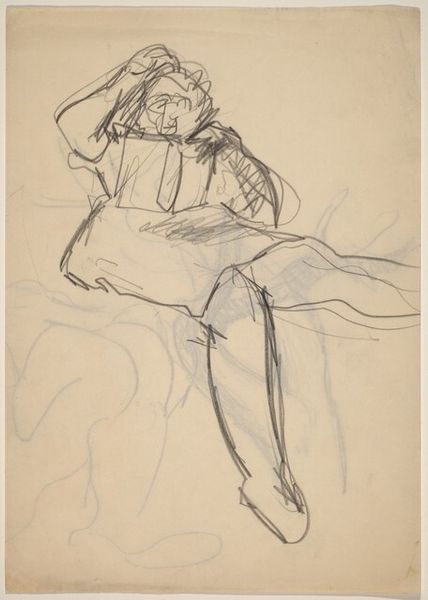

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

Dimensions: plate: 31 x 41 cm (12 3/16 x 16 1/8 in.) sheet (cut inside platemark): 32 x 48.8 cm (12 5/8 x 19 3/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: We're looking at "Gaby in a Chaise Longue," an etching by Jacques Villon. The print presents a woman reclining, with another, more ghostly figure looming behind her. Editor: My first thought is how raw it feels. The visible sketch lines, the unfinished quality… it's like glimpsing a moment still in progress, almost voyeuristic. Curator: Absolutely. Villon’s process as a printmaker emphasizes line and contour to build form. But, as you observe, it feels deliberately unresolved. You know Villon came from an artistic family, and would engage with the work of his brothers, including Marcel Duchamp. He really pushed boundaries. Editor: It makes me think about labor and the reproductive quality of prints, especially etchings. How many of these were produced? What does that do to our understanding of 'originality?' This isn't about singular genius, is it? It's about reproducible processes that bring art to a wider audience. And who exactly gets access to art? Curator: Very relevant points. Printmaking as a medium democratized art to a degree, allowing for broader distribution and thus access. But if we focus on Gaby as the ostensible subject – is the portrait intended to express something about the bourgeois society the sitter inhabits? And is there something revealing about Villon’s decision to make an etching rather than, say, an oil painting? Editor: Well, the deliberate ‘roughness’ counters a luxurious reading, which an oil painting might amplify. This seems to point towards showing how prints create the image itself, with all the manual processes on full display. Each line tells a bit about the making, rather than solely existing as a depiction of the sitter. And in regards to that society, notice how this Gaby is, after all, reclining... What labour does that suggest or conceal? Curator: An astute observation. We tend to focus on the artist’s hand and labour but fail to investigate those of the sitter. It's that inherent contradiction within art of this period that is so very rich. Editor: Looking at the details of labor that goes into printmaking – a mechanical, rather than emotional, lens, allows us a special insight here. Curator: Indeed. Thinking about the context of artmaking offers avenues for seeing beyond the surface. Thank you. Editor: A welcome opportunity to see process in production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.