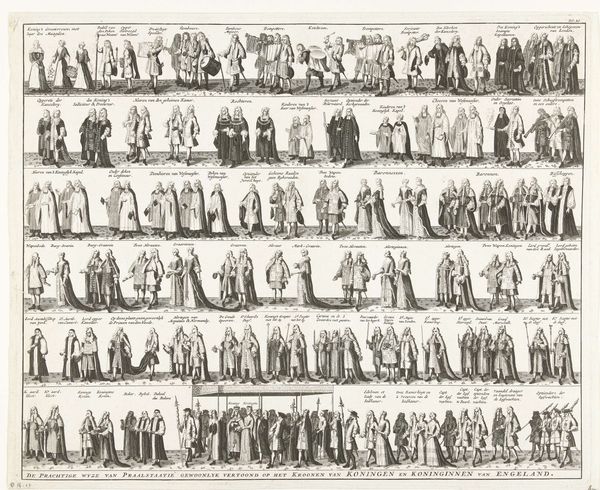

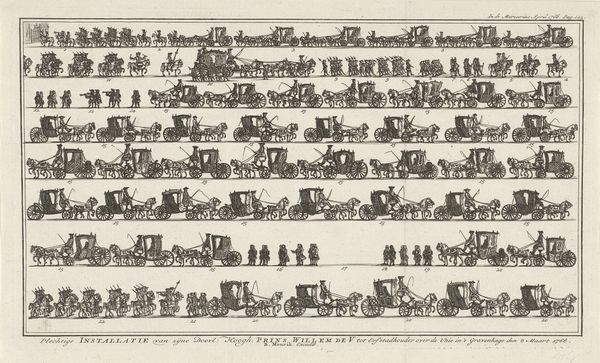

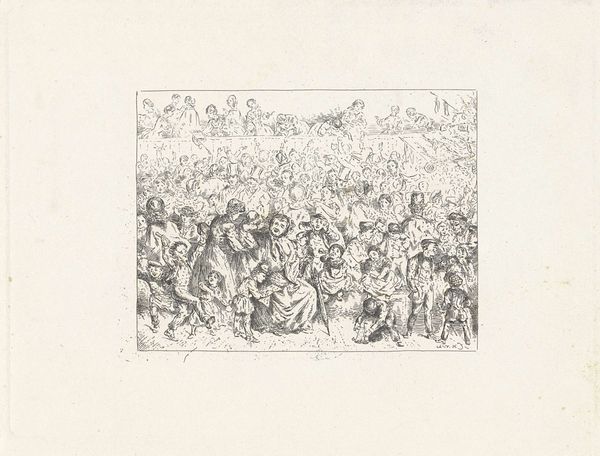

print, engraving

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 229 mm, width 285 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Charles Onghena created this engraving, titled “Heilig-Bloedprocessie van de paters Augustijnen, 1698”, sometime between 1816 and 1886. It presents a historical, almost encyclopedic, view of a religious procession. Editor: The immediate impression is one of meticulously ordered chaos. The eye jumps from row to row, trying to make sense of the tiny figures and elaborate vehicles, all rendered with remarkable precision. Curator: Let's consider that "precision". The print medium, particularly engraving, lends itself to this linear style. The material realities of producing such an image—the labor, the printing presses, the dissemination of prints as a form of visual record—are crucial to understanding its purpose and appeal. Think of it as a visual accounting, recording power dynamics through display. Editor: Absolutely, and I’d add that beyond record keeping, this procession and its depiction are loaded with symbolic meaning. Each float, each costume, would have represented a specific religious idea or figure, participating in a larger narrative of faith and communal identity. For instance, observe how the repetition of horses suggests power and dominion. Curator: Good point. The repetition extends to the production process, doesn't it? The labor is embedded in the layers, the time, and the industrialization of printmaking to share a certain version of authority or narrative, which, in turn, suggests mass appeal. Were such images consumed as simple documentation or aspiration for participating in religious community power structures? Editor: I'm swayed by that. It hints at layers beyond simple religious participation—that there are social and, perhaps, class connotations within such religious spectacle. Note the clothing differences—details in the depiction seem designed to differentiate participants. I see a deliberate hierarchy at play, with particular religious symbology designating class. Curator: Right. And through Onghena's engraving, these subtle variations were, quite literally, cast in hard lines to produce permanent, repeated images. What impact does industrial art have on personal identity within these movements? What I’m drawn to here is Onghena’s hand shaping a new cultural context around religious observance. Editor: A valuable, indeed powerful question that reveals, at least for me, a confluence of cultural, psychological and spiritual aspirations within these carefully crafted procession scenes. Curator: It prompts me to wonder: how many hands and how much deliberate ordering went into manufacturing both the real-world event *and* Onghena's print. Editor: Exactly. Thank you for drawing my attention back to labor because I realize these aren’t spontaneous images—both the making of the event and of the art requires extreme focus.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.