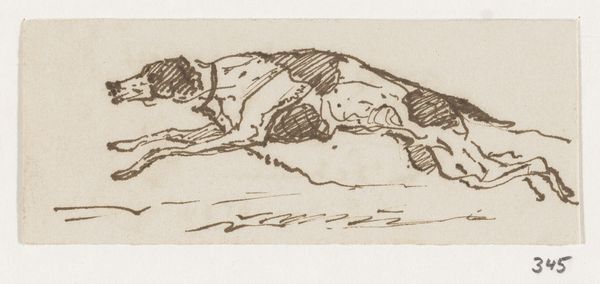

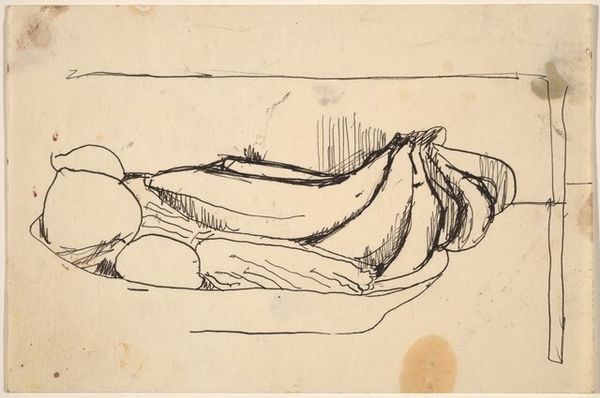

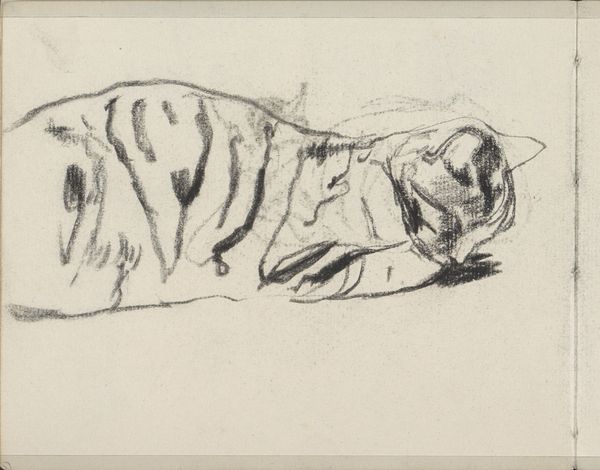

Dimensions: height 64 mm, width 112 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. Here we have Johannes Tavenraat’s "Jachthond," an ink drawing dating from around 1840 to 1880. Editor: My initial reaction is how evocative the economy of line is here; the dynamism is really palpable. The monochrome wash creates a somber mood, despite depicting an active subject. Curator: Absolutely. It's vital to see this image as situated within shifting human-animal relationships of that time. The artwork comes on the heels of increasing dog breeding and dog training that saw companion animals shift from utility, guarding and hunting, towards their role as empathic mirrors of our very selves. It prompts important questions about animal rights then and now. Editor: I appreciate the connection you're making. From a formal perspective, notice the lack of background detail? The minimal lines create this flat ground suggesting an emphasis not on its environment but on the shape of the hunting dog itself. It’s almost suspended in motion through its streamlined design. Curator: Consider though that such artistic choices further entrenched then-contemporary views of animals solely in relation to human use, negating their own realities of simply inhabiting space as autonomous actors in any landscape or milieu represented. This is an instance of anthropocentrism in Romantic artwork that demands closer critical investigation. Editor: I concur that such anthropocentric interpretations merit rigorous examination; I just am drawn to its sheer expressiveness and the mastery conveyed through skillful simplification of form and its composition and its tonality that all adds to a sense of drama in mid-movement—an impressive and affective aesthetic strategy deployed skillfully in Romantic tradition for which these artistic liberties create such visual depth with so few elements rendered explicitly for detail's sake! Curator: It’s crucial that we read Tavenraat's "Jachthond" not merely as an isolated instance of artistic expressiveness but in terms of broader conversations then about colonialism and resource extraction during this time of global expansion wherein working animals figured prominently in labor, land acquisition practices across subjugated territories, often functioning unwittingly instrumentally to extend systemic violence wrought on people and eco-systems as a result! Editor: I see that. I hadn't previously examined how form could reflect cultural ideology and oppression this way and am interested in delving further into sociohistorical meaning that shapes one’s appreciation when contextualized through such theoretical lenses! Curator: Exactly—art invites exploration; and inquiry across history through such interpretive paradigms empowers our sense of empathy toward building more awareness collectively that enables more engaged critical examination toward complex global inter-relations!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.