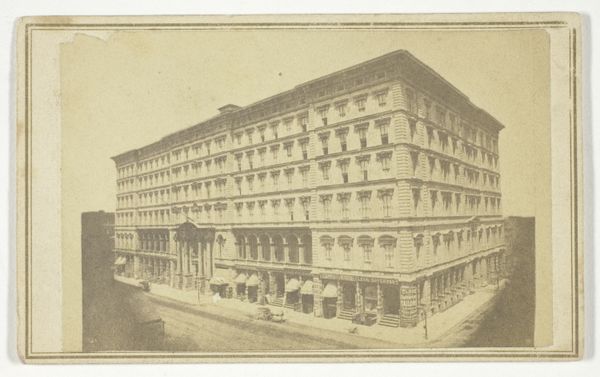

print, photography

# print

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

#

building

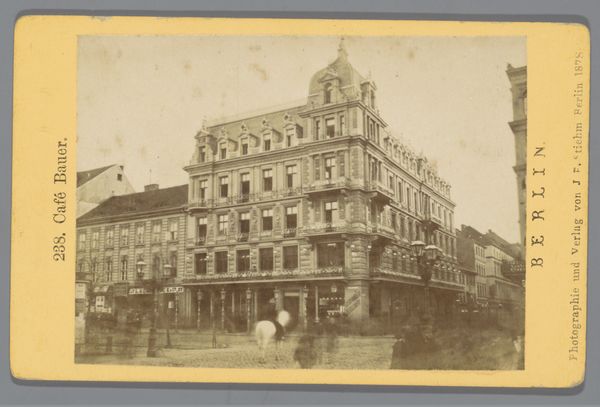

Dimensions: height 109 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

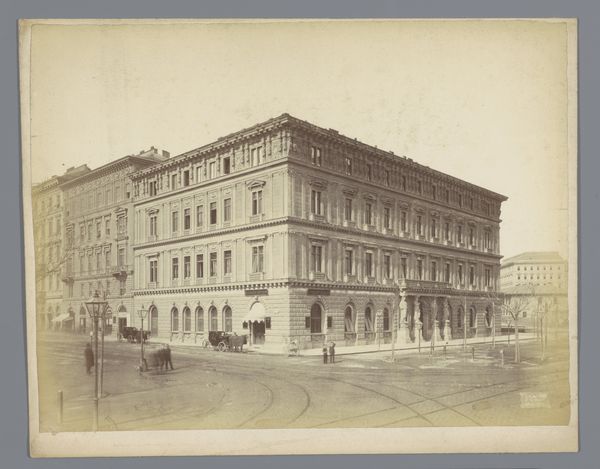

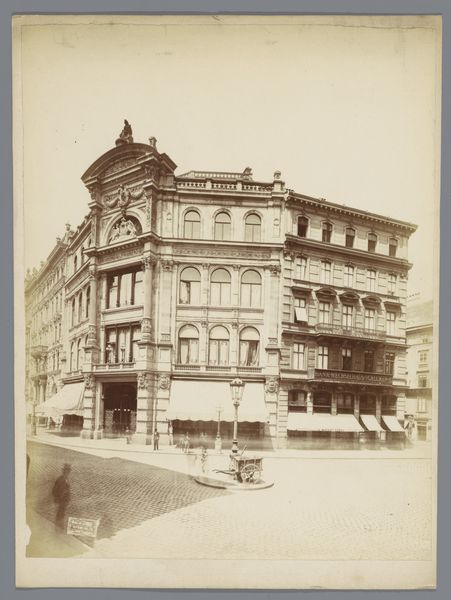

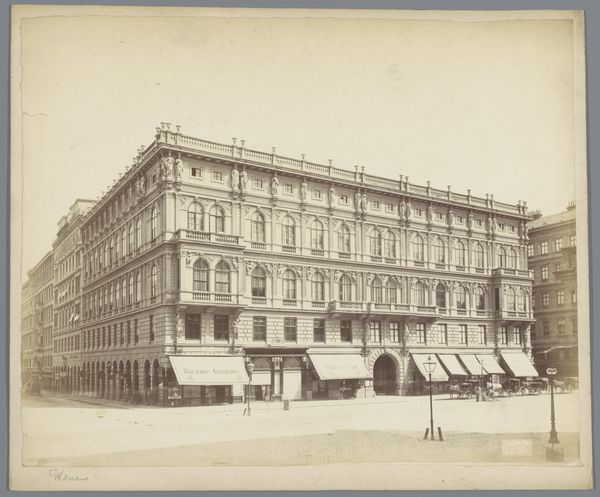

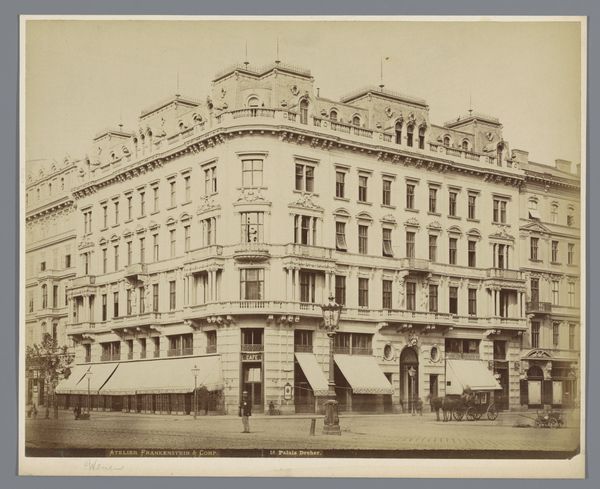

Curator: Looking at this early photographic print from around 1880, we see Johann Friedrich Stiehm’s "Gezicht op het Hotel Kaiserhof te Berlijn"—or "View of the Hotel Kaiserhof in Berlin." What strikes you about it at first glance? Editor: Bleak elegance, if that makes any sense? The architecture has this stately grandeur, but the sepia tone and the bare trees lend it a certain somber feel, like a stage set waiting for a play by Ibsen to begin. I immediately want to see what happens behind those windows. Curator: That somber elegance is a key element. Stiehm was working within a moment of rapid urban expansion and modernization in Berlin, and the Kaiserhof was emblematic of this. This hotel represented luxury and imperial power. Think about the societal implications of showcasing such grand architecture to the wider public through photography. Editor: True, there’s definitely a propagandistic quality here, right? Glorifying the Empire. But then there's also the subtle human element: the tiny figures strolling along the street, rendered anonymous by the camera. Are they awed by the architecture, or indifferent to it? I see it from both perspectives. Curator: The very act of making this photographic print had social implications. As photography became more accessible, it shaped how people saw themselves and their cities. How does it contribute to ideas about Berlin and German identity? Editor: For me, I think it’s the precision, the way every brick and windowpane is rendered with such detail. It screams order, power, aspiration—the kind of characteristics that probably played a part in defining Berlin’s image at that time. And then a new image was imposed after WWI and later after WWII with the bombings, reshaping both Berliners' understanding of Berlin’s self-image, the buildings’ symbolic weight changed—so charged. Curator: Exactly, and don’t forget that it was a key location of historical significance as a residence to prominent historical figures before the destruction of WWII and later complete demolition by East Germany. In essence, what remains now, ironically, is its photographic image and documentation as presented in Stiehm’s work. Editor: And now, we’re both picking apart the residue of what that photo now offers. This image—Stiehm inadvertently turned the Kaiserhof into an idea more powerful than any of its physical bricks and mortar. Art has strange paths like this in historical retellings. Curator: It becomes a symbol laden with shifting meanings, demonstrating photography's complicated role in shaping, representing, and even mythologizing places.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.