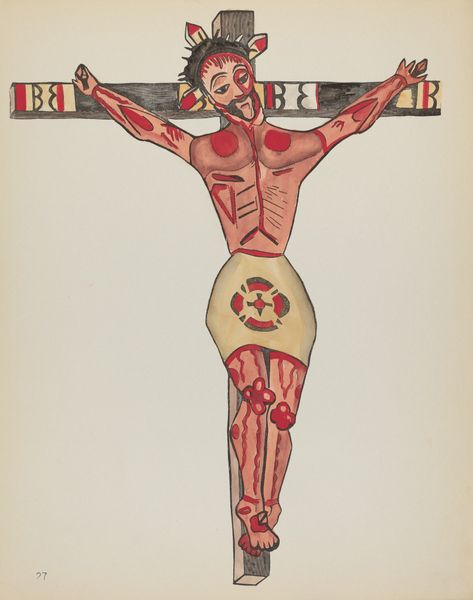

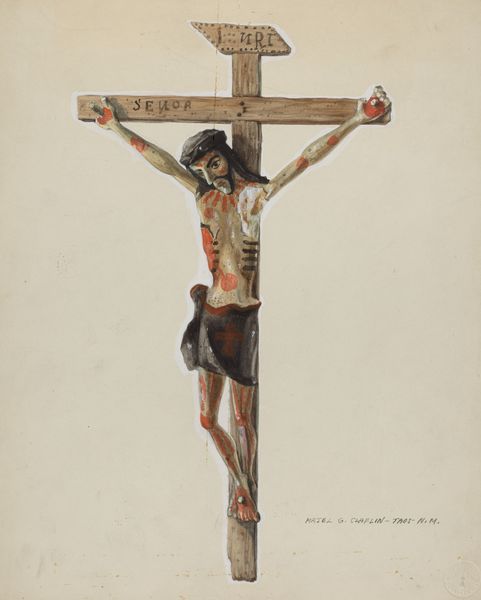

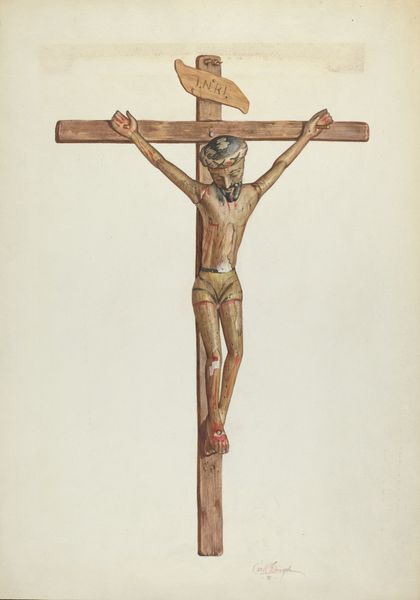

Plate 26: Christ Crucified, Taos: From Portfolio "Spanish Colonial Designs of New Mexico" 1935 - 1942

0:00

0:00

drawing, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

history-painting

#

portrait art

Dimensions: overall: 35.6 x 28 cm (14 x 11 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

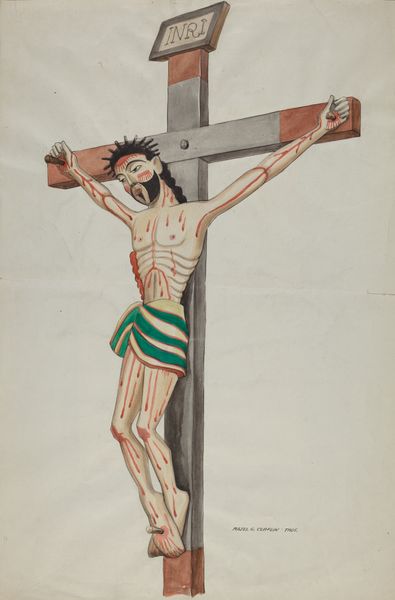

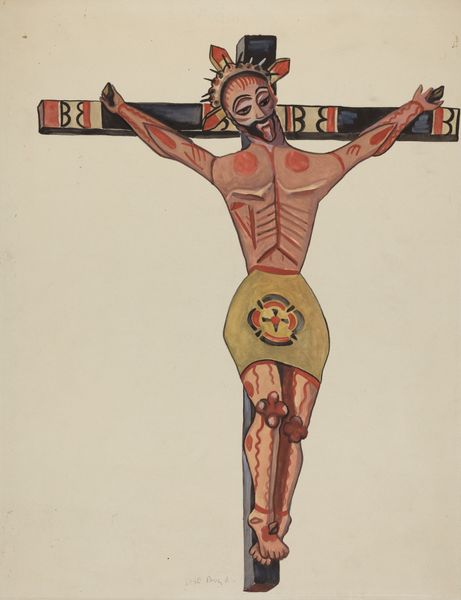

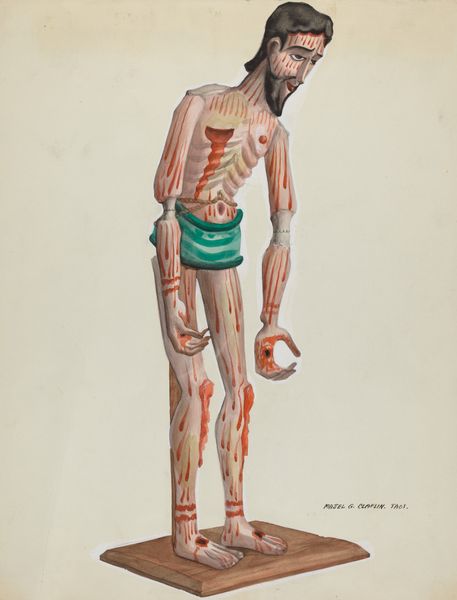

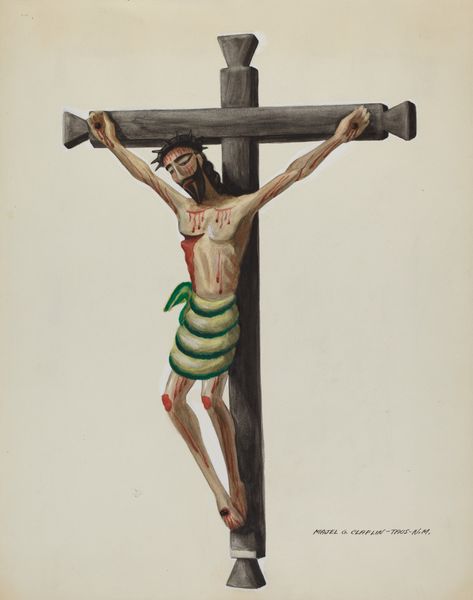

Curator: What strikes you first about this image? It’s titled "Plate 26: Christ Crucified, Taos" and it’s part of the portfolio "Spanish Colonial Designs of New Mexico," dating from between 1935 and 1942. Editor: The immediate impact is one of stylized suffering, isn’t it? The figure is gaunt and elongated; those red stripes give it a really stark visual. It's emotionally jarring. Curator: The use of those almost brutal red lines immediately pulls the eye. Notice how the anonymous artist renders Christ: elongated features, a sort of ethereal detachment. It echoes pre-Renaissance iconography. Editor: Yes, and situated in "Spanish Colonial Designs" that stylized, almost primitivist representation feels inherently political. It begs questions about power, about indigenous reinterpretations of colonial narratives. What are we meant to take away from this flattened almost graphic depiction of crucifixion? Curator: The power, I think, comes from that deliberate primitivism. It harkens back to early Christian art before it became naturalistic, drawing on older traditions. The artist uses the power of an established religious image to remind viewers of that original intensity. Think Byzantine iconography. Editor: But even in those iconographic traditions, there is typically an element of divinity. This Christ feels so deliberately human, marked, almost flayed. I find that compelling in its challenging presentation, its challenge of Eurocentric ideals and perspectives. Curator: And remember the New Mexico context! The work serves as a connection to New Mexican cultural memory, preserving devotional practice that has taken on a distinctive life separate from European traditions. This interpretation reminds people where they came from. Editor: Precisely. It also functions as resistance against dominant narratives. How does this representation of faith, altered by colonial experience, assert its identity? What about viewers then and now seeing the blood or violence; whose sensibilities does it really shock, or affirm? Curator: In confronting established symbols this artwork reveals a historical connection but also opens the way for individual reevaluation, even reclamation, doesn’t it? Editor: It’s this space, at the nexus of representation, power, and cultural inheritance, where true and ongoing change can hopefully begin.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.