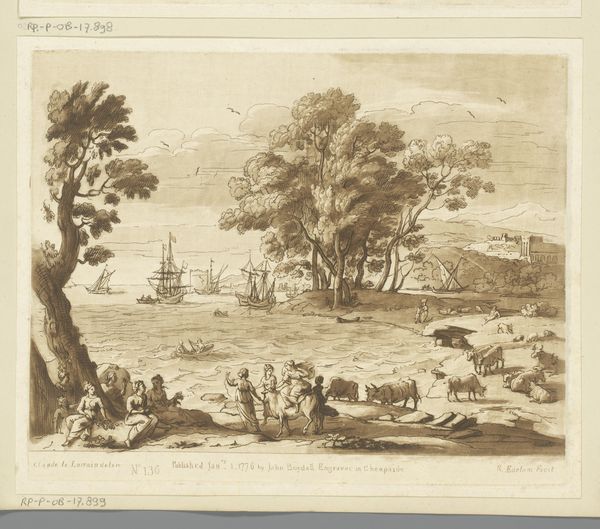

Dimensions: height 206 mm, width 256 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Richard Earlom's "Landscape with a Shepherd Couple and Cattle on a Riverbank," potentially from 1776, offers a compelling vision of pastoral life, rendered through etching and engraving. The artwork presents a classical scene brimming with idyllic charm, which evokes feelings of peace, but there’s a strange element too. What are your first impressions? Editor: It looks delicate, almost faded, but that gives it a sense of age and, somehow, permanence. The sepia tones soften the scene, while the cattle really seem to root it in material reality. There's labor embedded in every scratch and etched line that shows through the printmaking. Curator: The faded tone does contribute to the print's symbolic aura of history and bygone eras. The composition guides your eye towards distant, almost dreamlike ruins. What do you read into that scene? Editor: I think the artist uses printmaking to mass produce idyllic rural visions for commercial purposes and therefore makes the landscape consumable. Notice the way the print imitates a drawing? That is something unique to prints of this time period, especially landscape prints which came in series like this. Curator: Very astute observation. What resonates is how the etching recreates a harmonious space, yet it seems like one carefully designed for upper class consumption. The shepherd and shepherdess, their placid livestock, even the architectural ruins hint at the timeless appeal of a curated paradise. It's the type of visual narrative meant to reinforce idealized, cultivated memories, maybe even national identities, of an empire. Editor: It seems odd to use ruins like that, don't you think? Curator: Ruins in a picture offer reminders of civilizations and also represent a symbolic passing away and rebirth. They add grandeur, memory, a sense of profound, weighty understanding of cycles and civilization. Editor: True enough. Earlom seems invested in capturing the fleeting moments, though, in his time using modern methods for production and making images for a hungry market. In fact, prints and drawings such as these also formed a material record that was then available for collectors of these original artworks to remember a drawing that could have disappeared without a trace. A powerful medium, prints could transmit aesthetic taste, ideas and cultural values rapidly to a vast audience. Curator: Ultimately, it highlights the way even ostensibly simple landscapes carry complex cultural coding, even now as we consider how this print embodies idealized, perhaps unattainable worlds that connect to a culture's longing and anxieties about what has come before. Editor: Yes, there is labor everywhere, and the work and intention of it all matters now as much as when it was first published and printed. It really grounds my thinking.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.