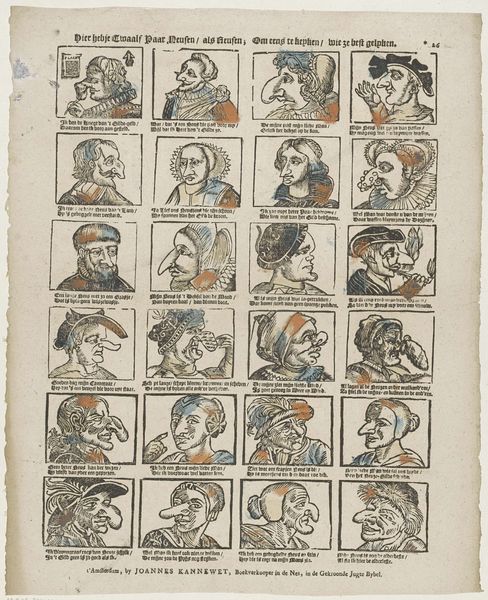

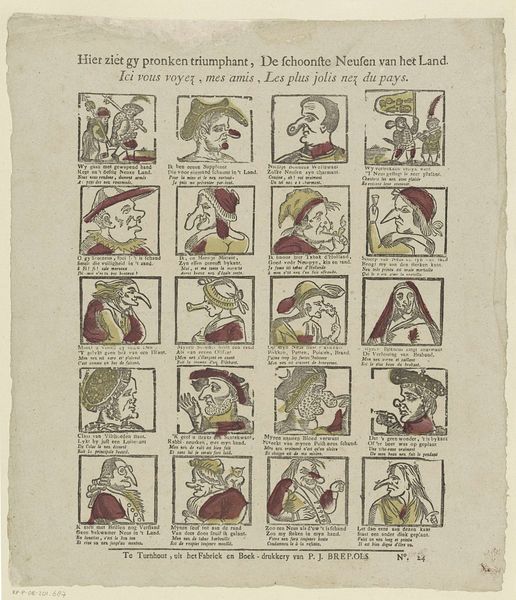

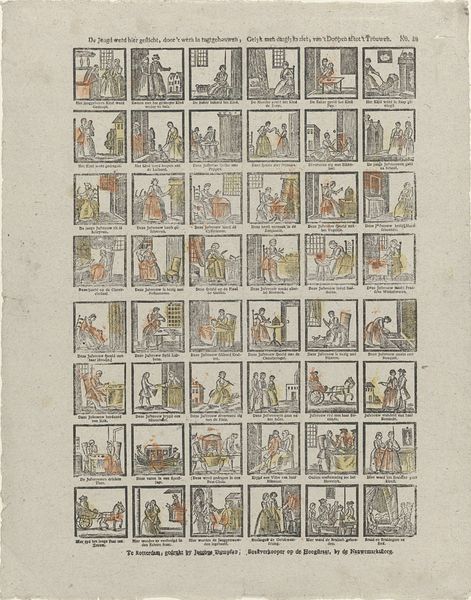

Dit 's Don Antonie Magino, / Die de planeeten uit kan leggen, / Die yder zyn gebreken zo / Maar vierkant voor de kop durft zeggen 1814 - 1830

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

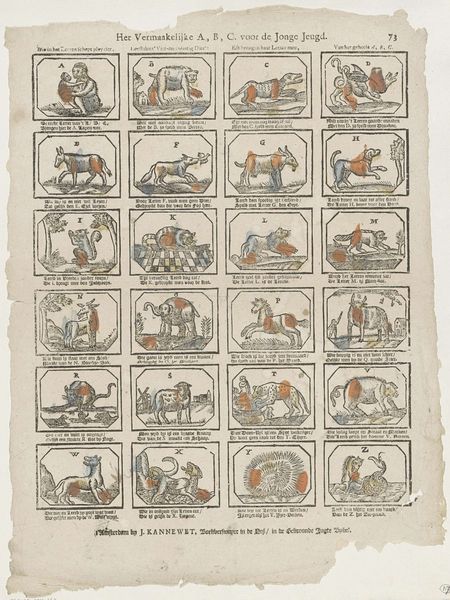

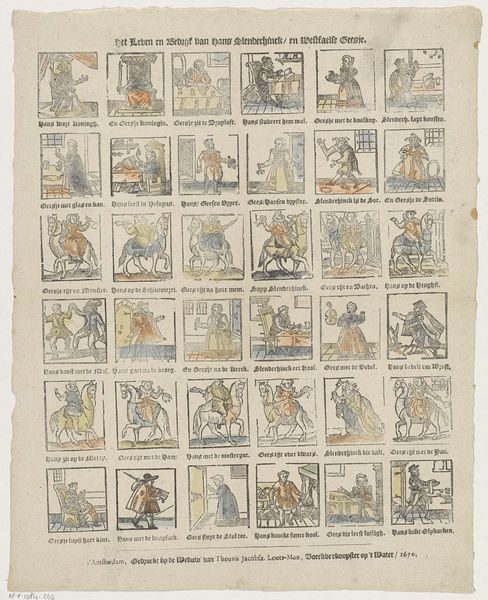

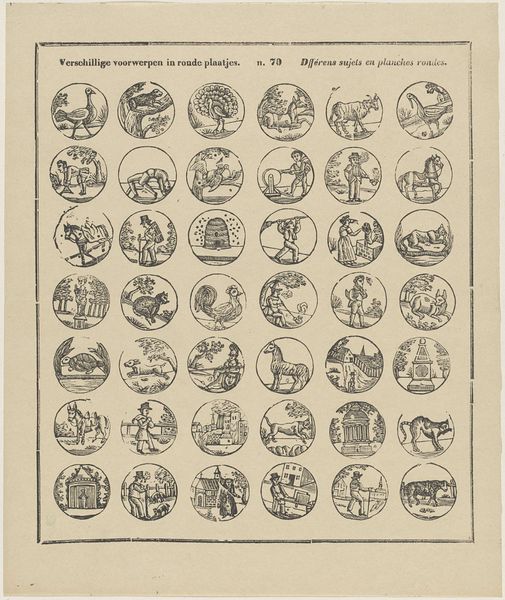

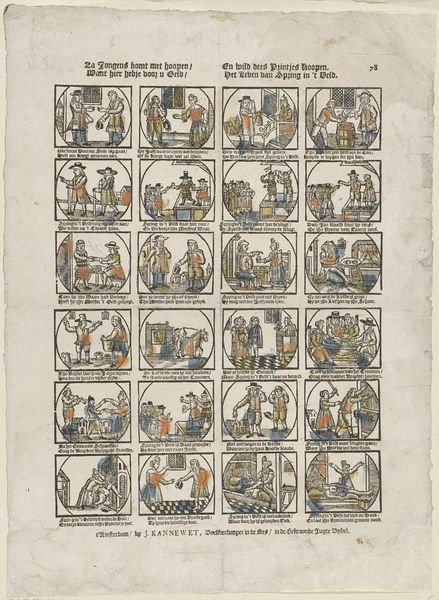

Dimensions: height 409 mm, width 335 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This piece immediately pulls you in with its almost comical, yet undeniably pointed presentation. It's got this quirky charm, but you sense there's a sharper observation about humanity nestled within. Editor: Absolutely, it has a definite satirical edge. What we’re looking at is an early 19th-century print titled "Dit 's Don Antonie Magino, / Die de planeeten uit kan leggen, / Die yder zyn gebreken zo / Maar vierkant voor de kop durft zeggen", dating from around 1814 to 1830, made by Barend Koene the Third. It presents a series of caricatured portraits with some striking, quasi-phrenological colour coding in red and blue. Curator: Color coding is fascinating. Like little explosions of emotion or character traits mapped onto the head. Is this about revealing the internal landscape through external depiction? Editor: Potentially. Romanticism was big at the time, but these faces lack its pensive moods. This almost clinical attempt at categorizing people feels more connected to emergent race science and theories of physiognomy and the project of figuring out what’s in people’s character according to external aspects, of, well, particularly their facial attributes. Curator: So the arrangement—all these heads lined up—speaks to a sort of… classification? Like putting personalities on display in a cabinet of curiosities? Editor: Precisely, each head could represent a specific personality or failing, dissected and labeled as objects. The little rhymes, by the way, refer directly to that. In some ways it speaks to an effort of popular science—in the publishing era, we start to see efforts in print making such things accessible to people that couldn't even read, and were certainly barred from a standard form of education. So this becomes both spectacle, knowledge production, and definitely commentary. It’s a critique through accessibility. Curator: I wonder, though, if there’s a wink and a nudge? Perhaps it acknowledges its own limitations or, dare I say, absurdities? This sort of raw, expressive quality feels deeply personal. Editor: Even the title, a bold statement about someone being blunt about flaws, can't quite obscure the social and scientific anxieties of the time that are baked into its production. This almost amateur aesthetic provides its political context as a type of rogue psychology. Curator: What I keep seeing is Koene asking us, with all its strangeness, to look past what's obvious—surface, immediate judgments. Maybe he challenges the very act of making up our minds too quickly? Editor: I agree completely. Looking closer allows us to tease apart the delicate strands of historical moment, humour, the personal imprint, and broader societal attitudes, and think critically not just about the art object, but how representation can uphold certain sociohistorical power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.