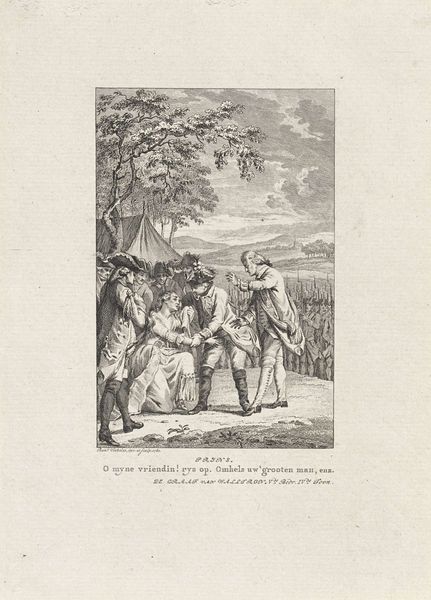

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

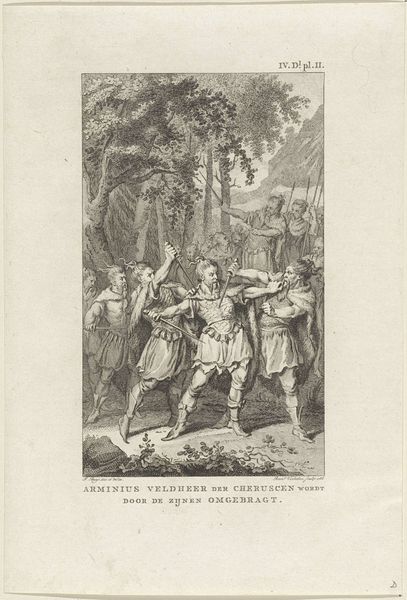

Editor: This is "Cadet en Charlotte knielen voor hun vader Charles," a 1774 engraving by Reinier Vinkeles, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. The scene feels incredibly staged, performative almost. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a snapshot of power dynamics and societal expectations meticulously crafted during the Baroque period. Vinkeles offers more than just a depiction of familial piety; he stages a scene ripe with commentary on gender, class, and the theater of leadership. Notice how the kneeling children—the girl in particular—embody submission, reinforcing patriarchal norms of the time. How does this subservience resonate with you, given the historical context? Editor: I guess it's hard to separate the art from the societal expectations of the time. But it does seem like their submission is being displayed for the benefit of the onlookers. Is that intentional, do you think? Curator: Absolutely. It's vital to remember the intended audience and the political climate. The 'history painting' aspect invites viewers to interpret this family portrait within a narrative of legitimacy and virtue. The meticulous detail—achieved through line engraving—renders textures and expressions with precision, directing our gaze and influencing our emotional response. This engraving promotes particular power relations as ideals to be adopted by wider society. How might this artwork function as a form of political propaganda? Editor: So it’s not just about family; it's about projecting an image of authority? It's interesting how those lines blur. Curator: Precisely! Art doesn't exist in a vacuum. Understanding the interplay of gender, class, and power unveils deeper layers of meaning and questions the narratives perpetuated by the artwork. This piece asks us to challenge the values embedded within these historical representations and to consider their lasting impact. Editor: I'm definitely going to look at these historical portraits differently now, keeping in mind what they were meant to say beyond the surface. Curator: It’s about finding the connections between the past and the present. Questioning the image is how we empower ourselves and our own readings of history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.