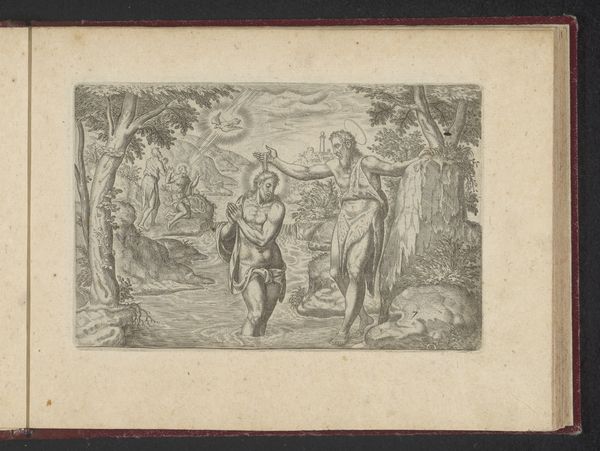

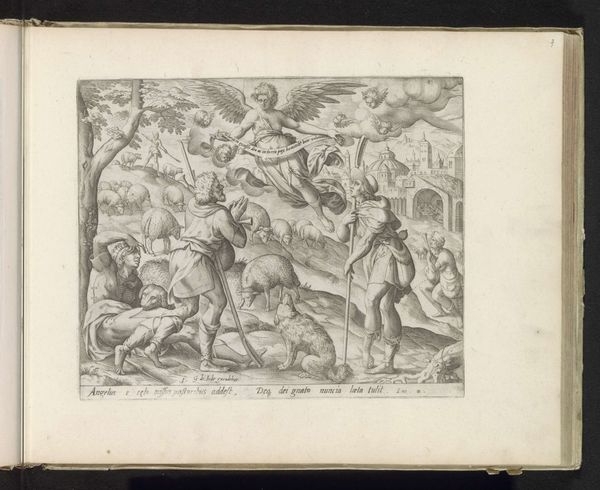

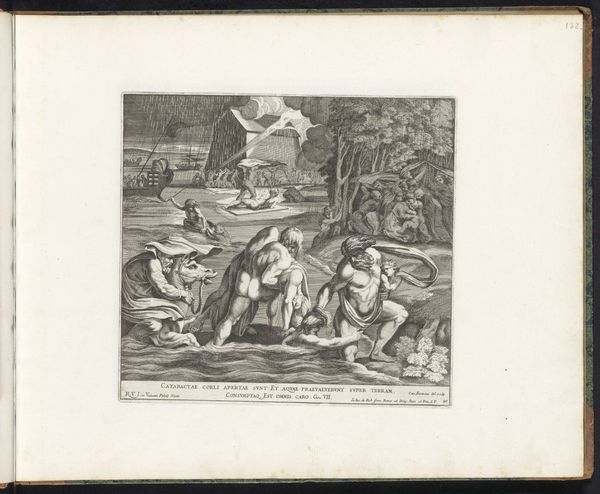

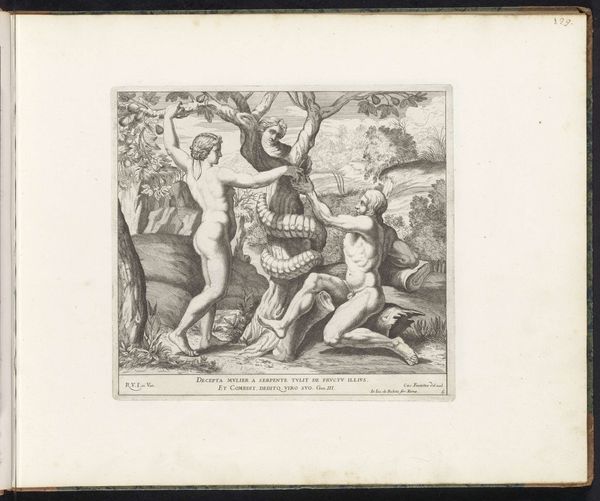

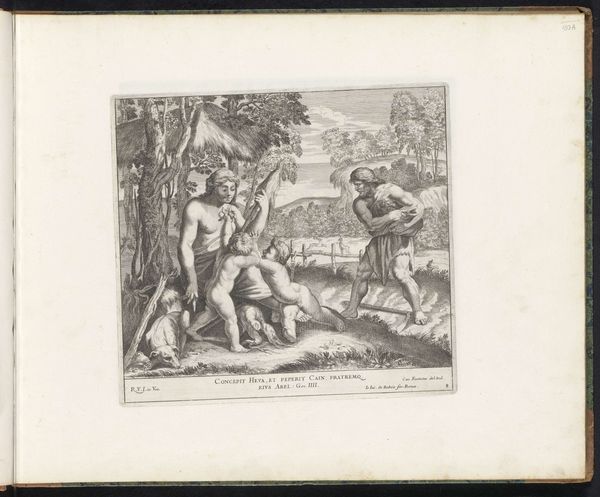

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 139 mm, height 137 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

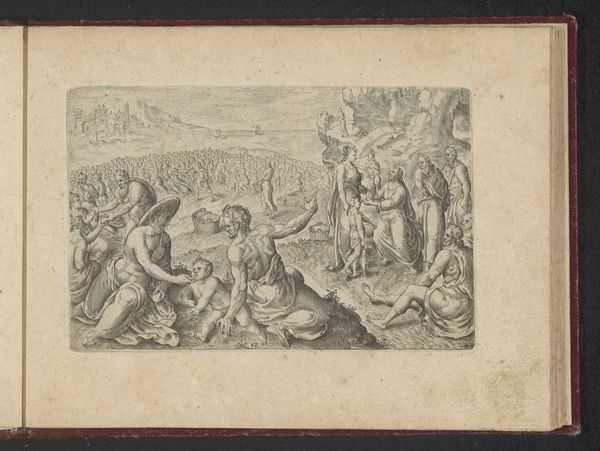

Curator: Looking at this piece, the eye is immediately drawn to the swirling chaos. It’s a print, an engraving, titled "Laatste Oordeel," or "The Last Judgement" by Philips Galle, dating back to 1573. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial impressions? Editor: My first impression is of profound unease. The composition, although intricate, evokes a sense of disturbance. There's a stark contrast between the figures emerging from their graves and the serene figure presiding above. The lines create tension and dynamism; I am interested in Galle's technical precision. Curator: Indeed. Considering the historical context, Galle was working during a time of religious upheaval and reformation. This piece visually represents a theological doctrine central to Christianity: the belief in a final judgment. Look at how Galle renders bodies emerging from their graves. This signifies the promise of resurrection for some, damnation for others. It echoes contemporary debates around salvation and morality that raged during that period. Editor: That's insightful. When I study the interplay of light and shadow, particularly how the bodies are modeled, I note how that reinforces the dramatic effect. The texture achieved through engraving creates a tactile quality, almost as if the figures are reaching out. The density of the lines near the bottom compared to the ethereal quality of the heavens really works to define the two spaces. Curator: Right, and considering that religious art served as a powerful tool for shaping societal values, Galle's piece acts as both a moral warning and an assertion of the Church's authority amidst a changing world. Think of the power structures implicit in depicting the ultimate power. Editor: Your analysis really gives perspective to that structure. Still, I'm intrigued by Galle's aesthetic choices. The elongated figures, the somewhat theatrical poses; these are very distinctive mannerist characteristics, drawing from the work of Italian artists like Michelangelo, but adapting it into Galle’s northern European context. Curator: Absolutely. By merging Italian mannerist style with prevailing religious and cultural anxieties, Galle created a work that's both visually compelling and laden with complex socio-political meaning. This work reflects its own time, and the timeless desire for justice and redemption. Editor: And it continues to speak volumes today, now informed by our awareness of its historical context. Curator: Yes, by combining our understanding of both context and form, we arrive at an even richer comprehension.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.