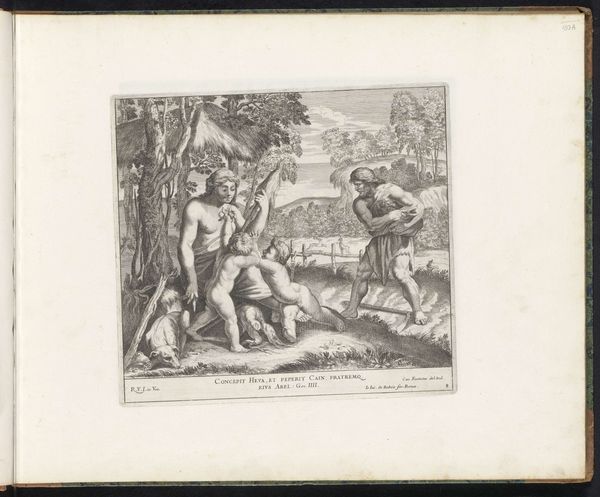

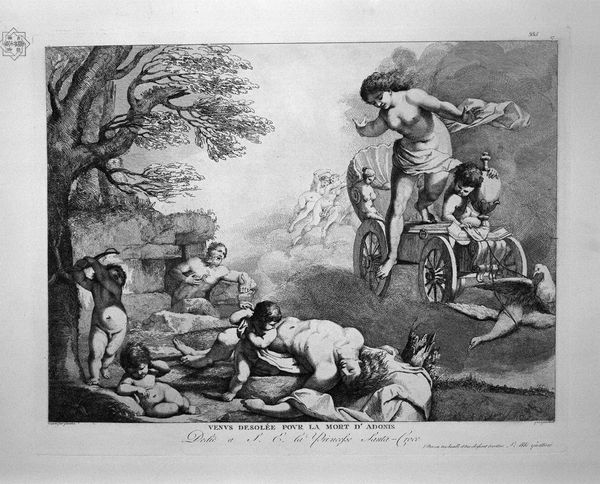

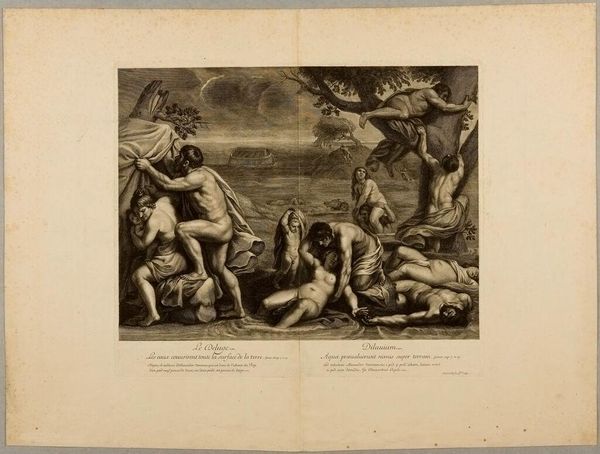

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

book

#

landscape

#

bird

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, created by Jacques Stella in 1657, is entitled "Les ieux plaisris de l'enfance" or "The pleasant games of childhood". It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you first? Editor: The scene feels…oppressive. These cupids are aiming arrows at a bird attached to a post; their innocent faces contrast so strongly with the implied violence of their game. Curator: Stella worked in Rome and Lyon and was known for his prints depicting allegorical and historical scenes. Childhood itself, emerging from Medieval approaches to children, began to take on new significance in the 17th Century. Do you find that shift reflected here? Editor: Well, Stella is showcasing what are seemingly harmless pleasures of children playing and the allegory between those playing and cupid seems a clear parallel, I cannot look past how casually cruelty gets coded as 'play'. We still see this in our culture when examining the intersections of class, race and what constitutes youth and innocence. The history of representation here carries a lot of complicated historical weight. Curator: It’s true that the pursuit is troubling. It might be important to keep in mind the traditions of genre painting. We can consider that genre pieces of childhood scenes tend to use archetypes, but even Cupid may have his dark side… Editor: Cupid’s supposed darkness feels like justification. In many ways the piece makes the idea of harming defenseless creatures, such as this turtledove, less accountable when placed into the hand of youth; a sentiment echoed in real life throughout modern colonial endeavors where those on the bottom are robbed of power by virtue of circumstance. Curator: I can see why the combination of innocent-looking figures engaged in a cruel sport gives you pause. It can certainly lead us to examine our assumptions. But to me, these cupids and the game also evokes innocence, joy, and carefree play. Childhood and children are always at once powerful symbols. Editor: Power is, again, not devoid of privilege here. Seeing art that's detached from its historic reality always leads to a detached response that never asks “to whom is it pleasurable?". That it feels ‘innocent' and ‘joyful’ requires that one accepts its paradigm as inherently joyful when many are left without options within such limited world-views. Curator: It really does provoke consideration. Thanks for that insight. Editor: Absolutely, an engraving always asks “who does it serve?”

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.