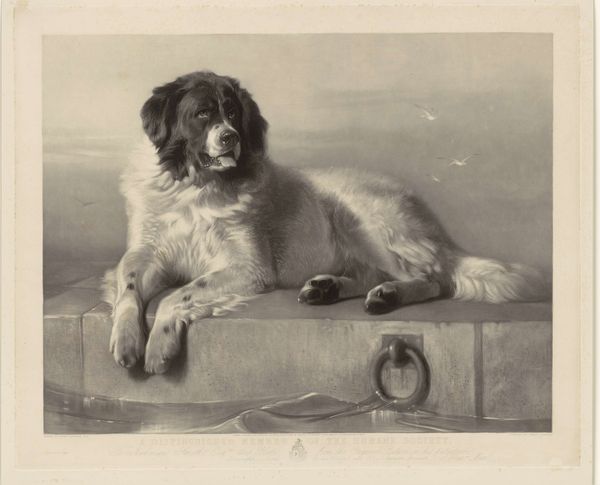

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van een hond, liggend op een stenen kade 1875

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

still-life-photography

#

dog

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 120 mm, height 320 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

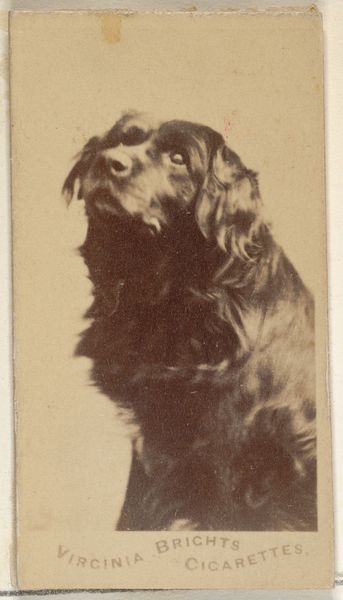

Curator: Let's take a closer look at this photograph from 1875 currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It's titled "Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van een hond, liggend op een stenen kade" which translates to "Photographic reproduction of a painting of a dog, lying on a stone quay". It's a gelatin silver print and the artist is anonymous. What strikes you initially? Editor: The texture. The fur, the stone, the way the light falls – it's incredibly tactile for a photograph. You can almost feel the coarse stone and the weight of that massive dog. There's a stillness that feels both serene and slightly melancholic. Curator: It's interesting you mention the stillness. Dog portraits were incredibly popular during the Victorian era and were often seen as stand-ins for their human counterparts. Representing loyalty, companionship, even status, they provided a mirror reflecting values that society cherished at the time. Consider the public role of animals during that time as it translated into art and its consumption. Editor: Yes, and I wonder about the photographic process. This gelatin silver print indicates a fairly involved industrial method – requiring specific chemicals, equipment and labor. Think about the consumption of materials versus the resulting fine art portrait of a pet. How much effort went into rendering this animal portrait through industrial means? Curator: Certainly, it’s worth remembering that advancements in photography democratized portraiture. But I am struck that what could be construed as art made via accessible means doesn't mean it loses inherent cultural cache. In this context, the photographic dog portraits mirrored the styles and poses prevalent in painted aristocratic portraits, albeit with a broader public appeal. Editor: It makes me also think about class and consumption here. The dog itself—likely a Newfoundland—was an upper-class pet, but here, photography made his likeness accessible and distributable on a mass scale. The accessibility also underscores questions about craft vs. fine art. It forces us to examine the relationship between mass-produced media and cultural symbolism. Curator: Ultimately, this photograph serves as a fascinating lens through which we can examine Victorian society, their relationship to animals, and the rise of photography as both an art form and a social phenomenon. Editor: I agree. Analyzing the layers, the materiality, and societal role helps us understand art beyond aesthetics; and its intricate connections to history and mass appeal.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.