![Untitled [half-length view of a young man] by Jeremiah Gurney](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2VlOTQxMDA3LWQ5MGUtNDJiYi1hZWI1LTM2ODAwYTZmODJiMi9lZTk0MTAwNy1kOTBlLTQyYmItYWViNS0zNjgwMGE2ZjgyYjJfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

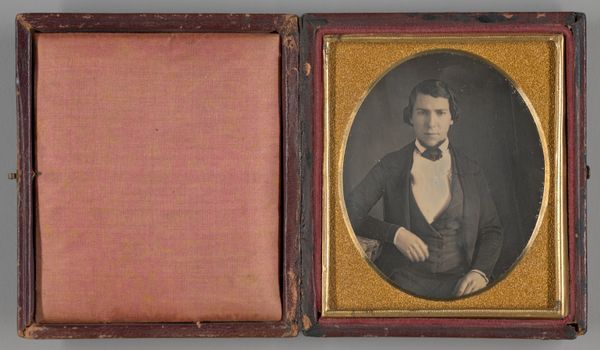

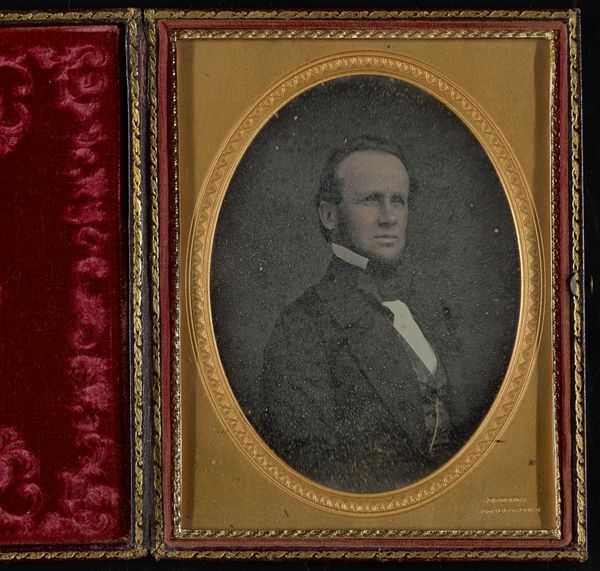

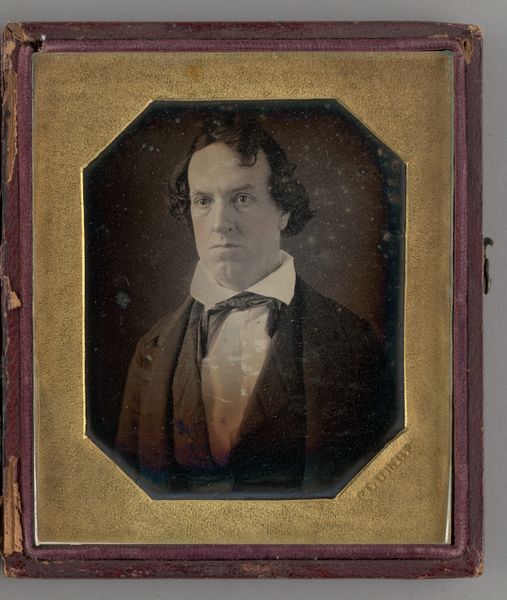

Untitled [half-length view of a young man] 1852 - 1858

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 4 1/4 x 3 1/4 in. (10.8 x 8.26 cm) (image)4 3/4 x 3 13/16 x 3/4 in. (12.07 x 9.68 x 1.91 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at this, an untitled daguerreotype portrait from the 1850s by Jeremiah Gurney, housed in its original case at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The richness of the case itself! What’s your first impression? Editor: It has such an air of solemnity, almost melancholic. The young man’s gaze is direct, but there's a softness too. And the presentation in this little case, like a jewel… it emphasizes intimacy. Curator: Exactly! Daguerreotypes were precious objects. Consider the process: a highly polished silver-plated copper sheet, meticulously sensitized to light with iodine fumes, exposed in the camera… each one is unique. No negative meant no reproduction. This man sat, still, for what must have felt like an age for a single image. Editor: And that underscores its significance, right? In a society beginning to grapple with industrialization, the rise of mass-produced goods, this becomes a way to assert individuality, even status. The man’s clothing - a patterned vest and a bow tie - and the decorative case signal middle-class aspirations. Photography, early on, mirroring painted portraits in function for certain classes. Curator: Precisely! The democratization of portraiture through technology but within established hierarchies. I wonder about the relationship Gurney, the photographer, would have had with the sitter. There's a business transaction involved, a negotiation of image and identity... The choice of frame, the lighting... Editor: And the accessibility that Gurney's studio offered – not just in terms of affordability compared to painted portraits, but also geographically. His presence in New York, a burgeoning urban center, speaks volumes about the cultural shifts of the time. The distribution networks developing rapidly at this moment really played a central role. Curator: Good point, his work documented that ascent in real time, one face at a time. The silver shimmering from the metallic plate lends the image almost ghostly quality – time itself captured and solidified in a delicate object. It really does capture an historical moment of transition. Editor: I'm left considering what this single image really communicates when removed from it's immediate audience of family and friends for display in an institution such as this. A solemn image turned historical object, still containing a sliver of that original solemnity after all.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.