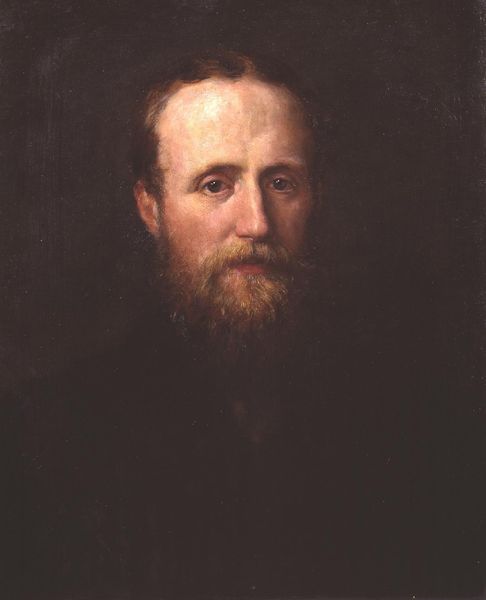

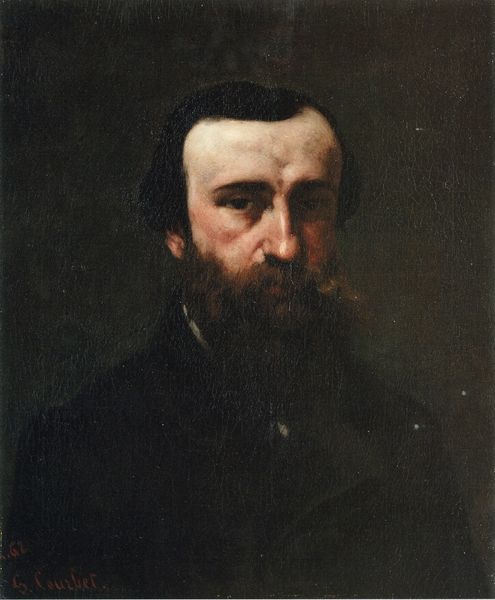

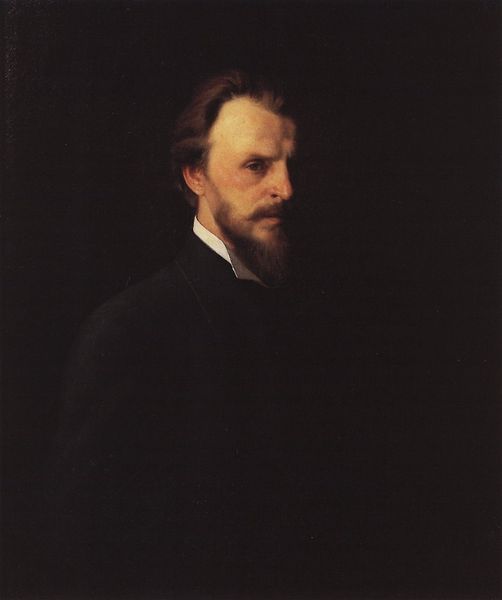

Dimensions: 17 x 14 in. (43.2 x 35.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an intriguing photographic self-portrait created sometime between 1856 and 1859. The museum attributes it to Joseph Kyle. Editor: The immediate impact is quite stark. It’s a somber image, cloaked in deep blacks and grays, evoking a sense of introspection. Curator: It’s striking how the absence of color allows us to focus on the materiality of the photograph itself, its texture, the evident process of its making. Photography in this era was hardly a point-and-shoot affair; it was an alchemical process. How did Kyle, as the photographer, grapple with controlling the means of production as also its subject? Editor: Absolutely, the portrait captures an emerging sense of selfhood. Look at his eyes, a central symbol; they're so penetrating, seeking perhaps to define the man behind the lens, an unveiling of identity through carefully controlled image-making. The long beard carries a heavy cultural weight, speaking to notions of masculinity. Curator: That’s right. Facial hair in that epoch was as much a societal symbol as it was a matter of individual style. But consider, too, the collodion process: the materials required, the expertise needed to achieve this likeness. Did this not confer a certain status onto both artist and sitter, intertwining social capital with the means of photographic production? Editor: It seems intentional. The heavy beard can also be a signifier of artistic or intellectual gravitas. Artists in the Romantic era often cultivated a particular visual image as a mark of genius. The deep shadow seems symbolic, as if concealing parts of himself while revealing enough to invite viewers to engage. Curator: Precisely. The image plays in a fascinating dialogue with class, labor and the relatively new possibilities of mass image creation. Early photography, although involving laborious practices, became progressively widespread and so it changed the role of visual depiction of individuals in the society, no longer limited to wealthy classes. Editor: I see this piece more as an exploration of individual character in an era where photography was emerging as a new medium to investigate the depths of identity. Its appeal lies in its haunting emotional resonance— a single individual confronting his existence through symbolic portraiture. Curator: Well, that's a rather succinct summary! It has certainly sparked reflections about its artistic implications in the rapidly shifting material landscape of 19th-century visual culture. Editor: Indeed, and perhaps even prompts us to ponder about how people perceive themselves and choose to present a face, sometimes somber or dramatic, to the rest of the world through crafted self-image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.