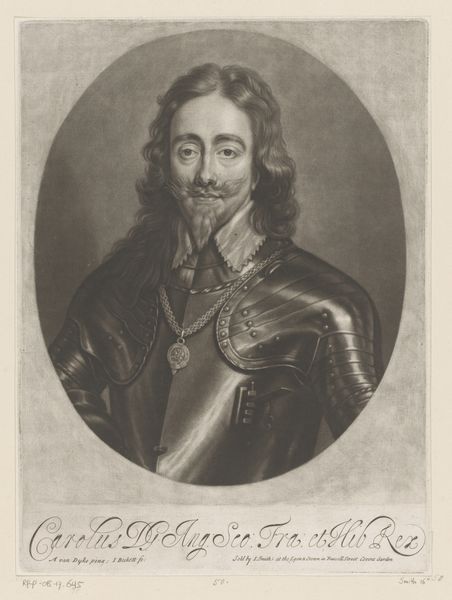

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 10 1/8 × 6 15/16 in. (25.7 × 17.7 cm) Sheet: 11 in. × 7 13/16 in. (27.9 × 19.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: William Faithorne the Elder created this engraving, "King Charles I," sometime between 1653 and 1663. It's currently housed here at the Met. Editor: There’s a melancholy gravity to it, isn't there? The dark hatching creates this somber mood. He appears both regal and trapped. Curator: I agree, and think that gravity stems in part from the very nature of printmaking in the Baroque era. The process—the cutting, the inking, the pressing—it all requires immense labor to produce multiples. Each impression becomes an artifact of that toil and is a method for dissemination, reflecting both artistic skill and workshop practices. Editor: Absolutely. This was produced following the English Civil War and Charles I's execution, right? I think the image takes on a poignant significance as a carefully crafted, mediated representation of a deposed and executed king attempting to grapple with themes of power, legacy, and martyrdom. It speaks to the complexities of memory. Curator: Consider also the materials. Copperplate engraving allowed for incredibly fine lines, a smoothness not found in woodcuts of the time. That precision speaks volumes, lending an air of legitimacy but also almost a mass-produced aura of the fallen king, if that makes sense. This also makes this image fit within portrait conventions while simultaneously making an argument through skillful deployment of available techniques and new developments. Editor: And let's consider what "portrait conventions" were upholding. In his royal garb and oval frame, Charles projects a particular construction of masculinity and power—divine right is visually signaled in a way that cannot be separated from contemporary discussions of identity and rulership in a tumultuous socio-political context. His armour, necklace and draped cloth adds more context to understanding social relations and ideology during a time of revolution. Curator: Looking at it from this lens we can also analyze Faithorne's strategic role: He wasn't merely copying Van Dyck; he was translating an image through a very particular mode of reproduction—and that reproduction carries its own social and political weight. What sort of workshops allowed such precision and distribution? The history is inscribed within. Editor: It makes us consider the consumption and circulation of the image itself, who it was intended for, and how it might have functioned to negotiate memory, trauma, and ideological contestations in the wake of a seismic political event. Curator: Exactly! A tangible object imbued with potent, albeit mediated, historical force. Editor: And those etched lines remind us that no image, regardless of intention, exists outside of the complex web of social power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.