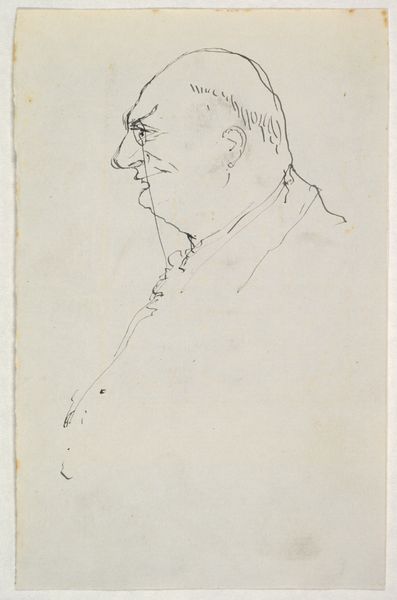

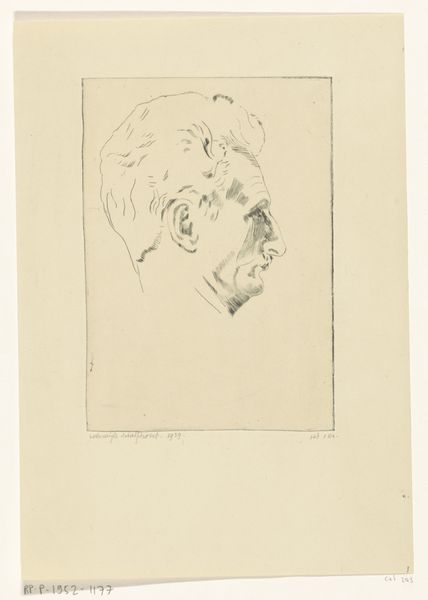

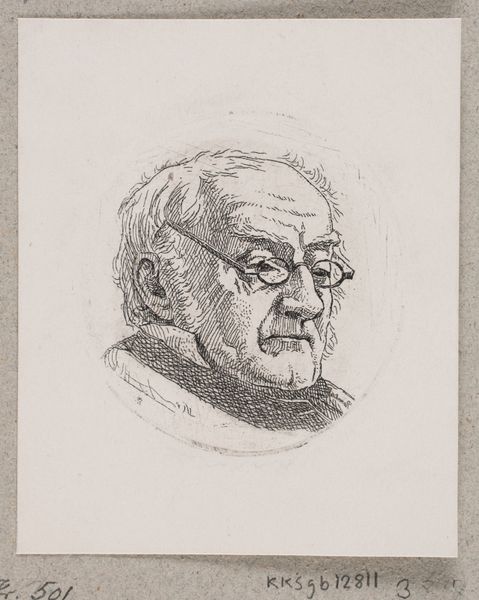

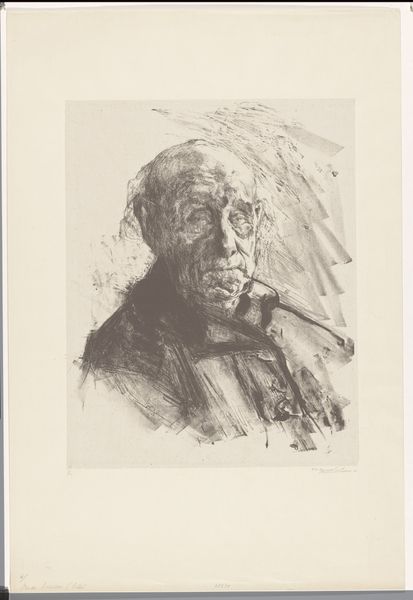

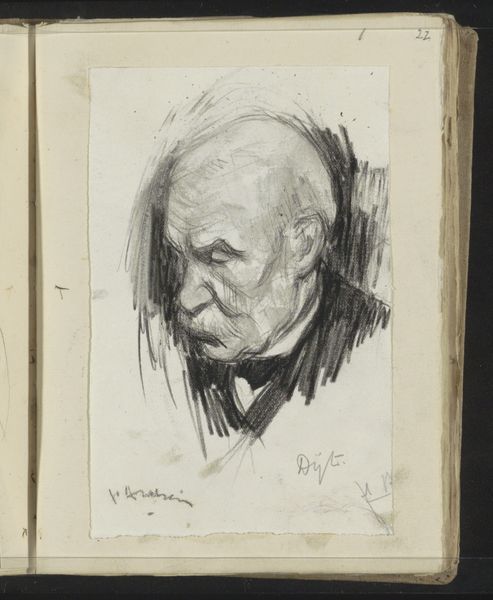

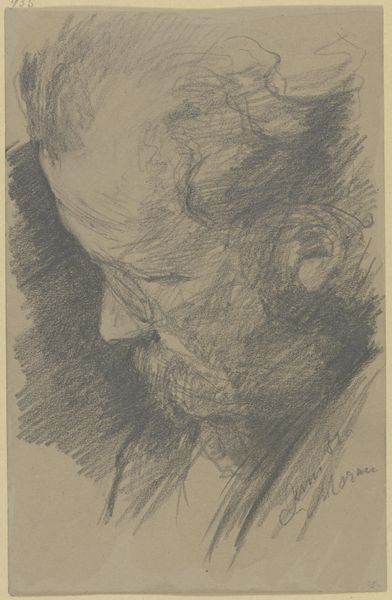

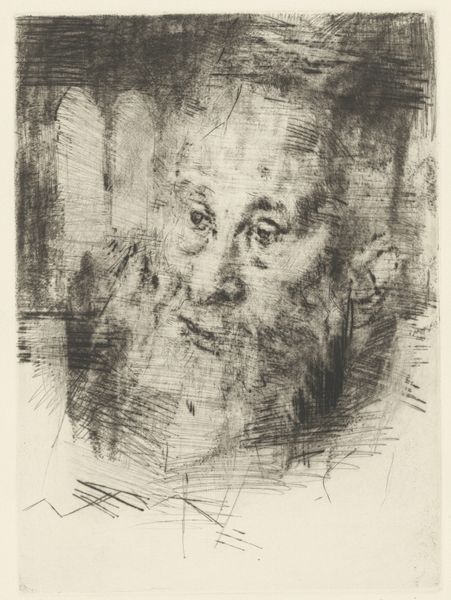

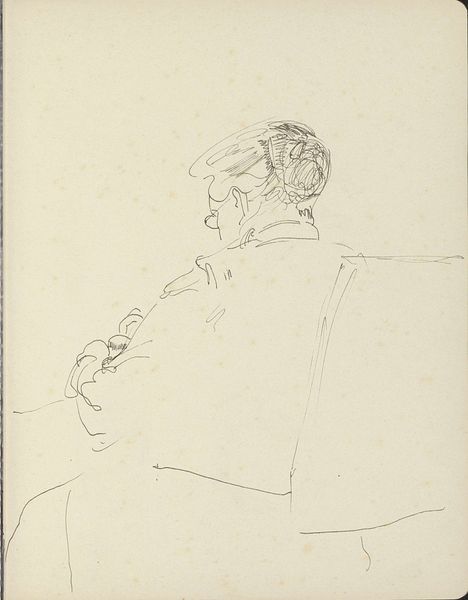

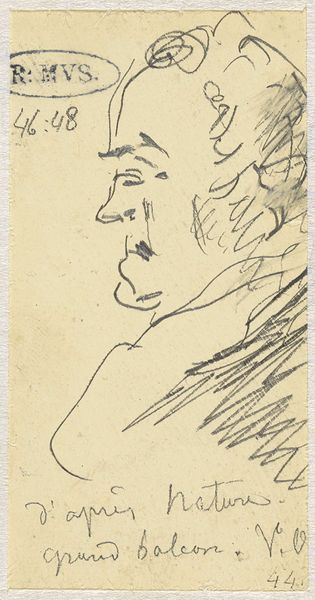

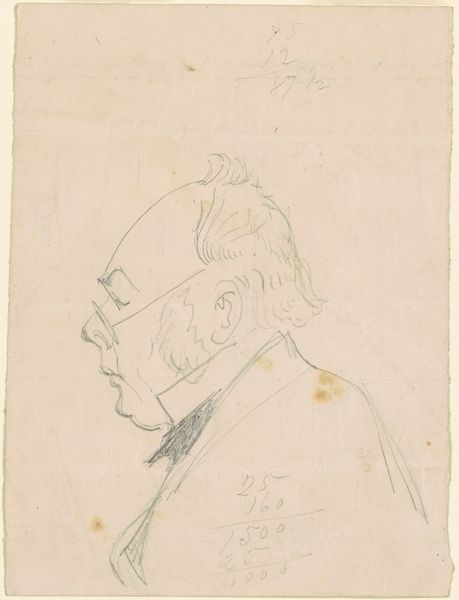

drawing, paper, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

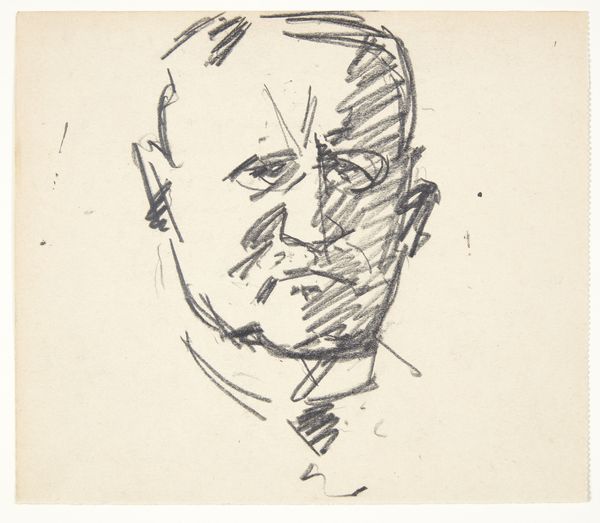

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

facial expression drawing

#

light pencil work

#

16_19th-century

#

pencil sketch

#

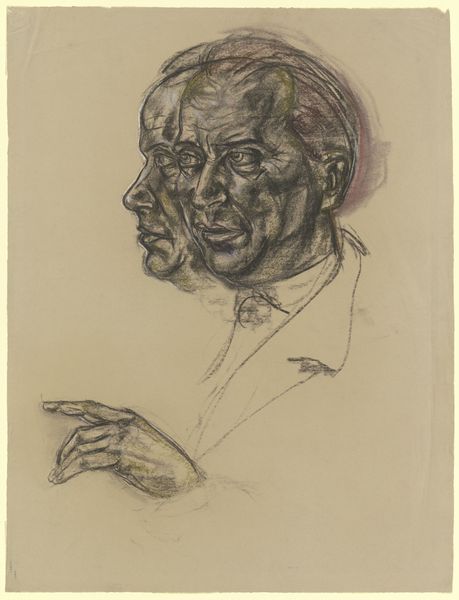

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

portrait reference

#

german

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

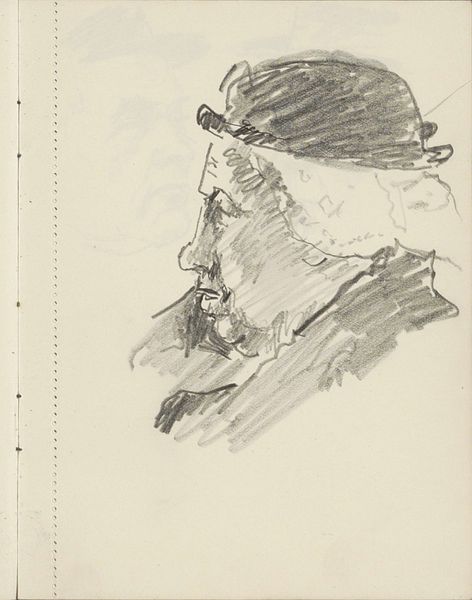

Curator: We are standing before Wilhelm Altheim's 1892 pencil and graphite drawing, “The Artist’s Father,” housed here at the Städel Museum. Editor: It’s a tender drawing, isn’t it? There's a profound quietude emanating from the man's bowed head and soft lines, and he appears almost burdened by contemplation. Curator: It's fascinating to view it through the lens of social history. Consider the role of the patriarch in the late 19th century. Drawing his father becomes an act of documenting authority and, perhaps, negotiating a changing paternal identity within a shifting social landscape. Editor: And the way the glasses are rendered--almost a barrier but also a means of seeing— adds another layer. Is he really seeing, or simply perceiving through established structures and limitations? Could it be seen as a critical observation of inherited ideology, the "spectacles" of societal expectation placed upon the son? Curator: Certainly. Furthermore, the very act of Altheim, a German artist, creating such an intimate portrait within the conventions of academic realism suggests both reverence and a desire to accurately capture a particular type, maybe even to freeze a fading archetype, of the patriarchal figure in German society. Editor: I find myself considering the father's gaze--directed inward, or downward towards a book or newspaper, lost in the written world. In this rendering, does the "word," both in literary and social construction senses, hold sway over his very being and position within family and society? Curator: An insightful question. And this drawing is particularly interesting when we think of Altheim as part of a generation experiencing rapid industrialization and changing class structures. He captures this tension through the soft, intimate quality of his medium while the very *act* of documentation also lends a sense of archival importance. Editor: So it’s about personal observation within sociopolitical shifts? It invites a lot of questions. Curator: Exactly, and art should do precisely that! It prompts introspection, it illuminates connections, it pushes us to engage critically with the past as it informs our present. Editor: I agree completely. Viewing this father-son exchange—recorded in such a humble medium—has been surprisingly evocative, actually, triggering reflections about my own family’s history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.