Dimensions: image/sheet: 23 × 28.3 cm (9 1/16 × 11 1/8 in.) mount: 44.6 × 56 cm (17 9/16 × 22 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

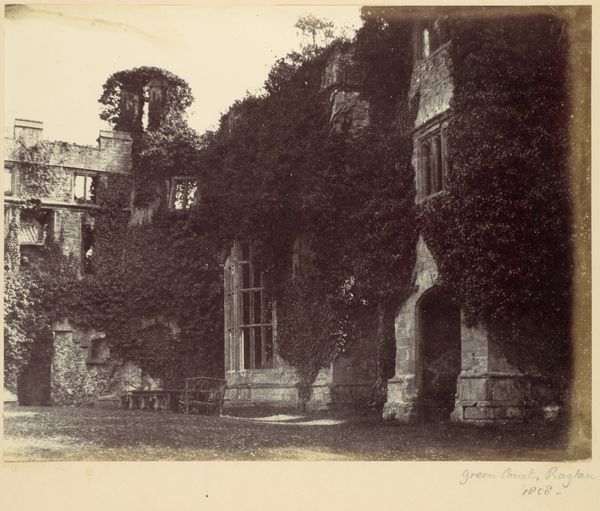

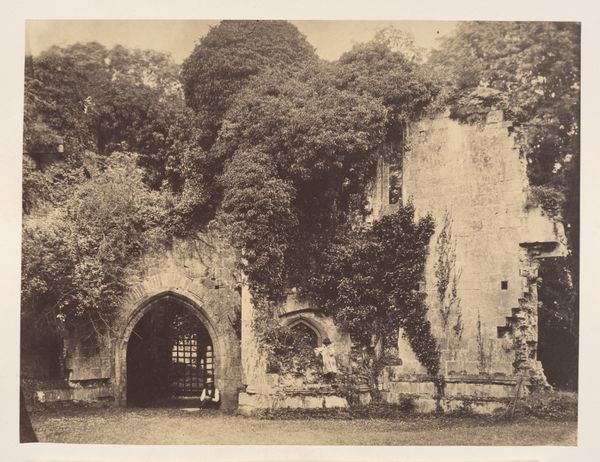

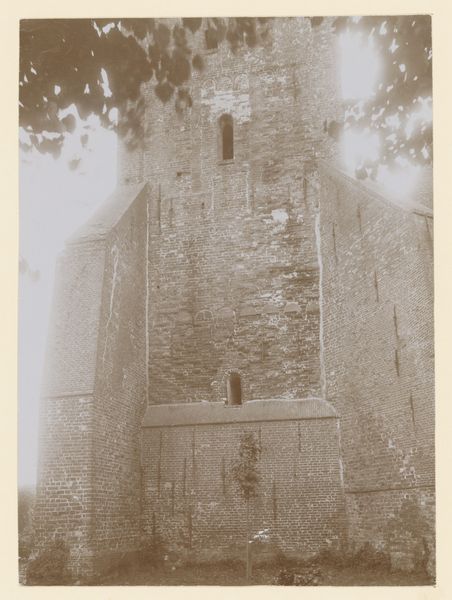

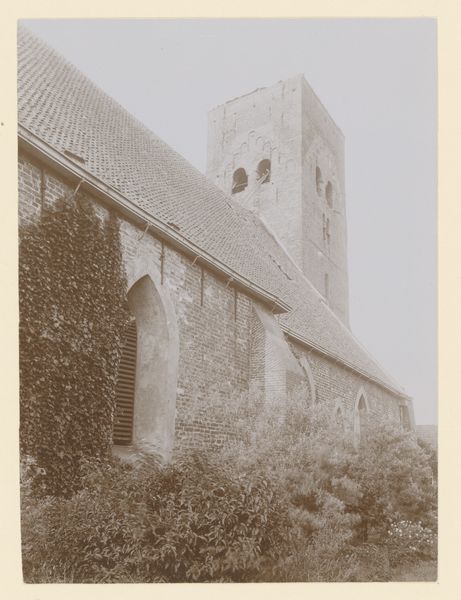

Curator: This is Thomas Marcus Brownrigg’s gelatin silver print, taken around 1865, of Muckross Abbey in Killarney. What are your first thoughts? Editor: Ruin and reclamation. The stone structure overtaken by organic matter... ivy snaking up the walls, almost obscuring the architectural details. There's a real tension between human construction and natural decay here, isn't there? Curator: Precisely! The image resonates deeply within a particular cultural narrative. The ruined abbey becomes a poignant symbol of the dissolution of Irish monasteries under British rule, resonating with themes of religious persecution and cultural loss. We can analyze this within a framework of post-colonial trauma. Editor: But isn’t it equally fascinating to consider the labor, the specific photographic chemistry involved? Look at the gelatin silver print; a delicate, carefully produced object. And the stonework itself. The repetitive acts of quarrying, shaping, and placing those stones—labor invested to build then undone by time. Curator: True, and Brownrigg's choice of photography, still relatively new, becomes crucial. The very act of capturing this decay serves as an act of preservation and a testament to the abbey’s enduring significance in the face of erasure. Think about how photography then becomes tied up with romantic ideals of memory and cultural identity. Editor: Consider the darkroom too, a site of labor that transforms the light captured in the lens. This process requires particular spaces, tools, and the physical labor of the photographer. It renders something supposedly "ephemeral," the decay, as lasting matter. Curator: Exactly, these competing ideas become entangled. And so the ruins themselves challenge concepts of national identity as an unwavering monolith. They expose layers of complexity within narratives, allowing for interpretations beyond singular power structures. Editor: A picture seemingly capturing a lost era. Still it requires so much artifice to produce and materialize in that very loss. Both beautiful and unsettling, isn't it? Curator: I agree. It urges us to see beyond the simple image and explore those historical and societal fault lines it brings into sharp relief. Editor: And equally to appreciate the means that brought these materials into contact. I can now look at any photograph with new awareness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.