print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

perspective

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 304 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

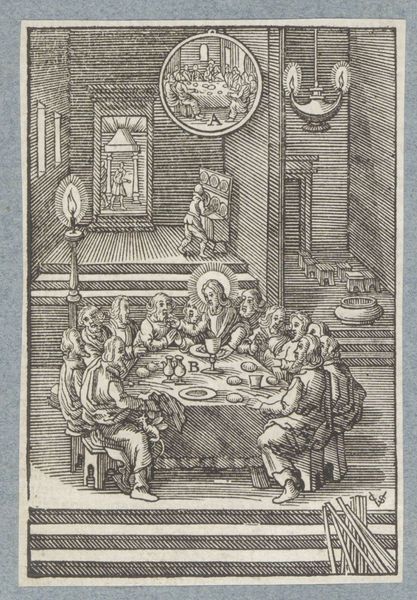

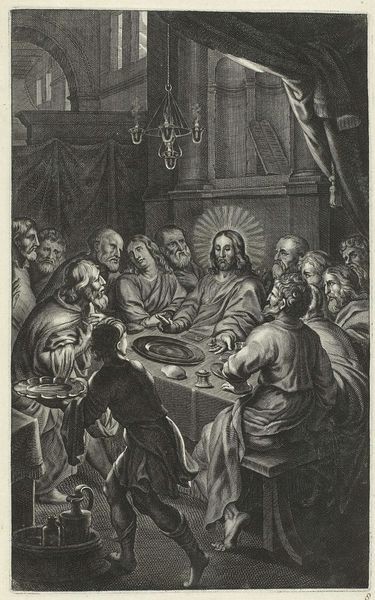

Curator: Looking at this engraving of "The Last Supper", made sometime between 1581 and 1633, after Theodoor Galle. You are immediately struck by the lighting aren't you? Editor: Absolutely, it's like a stage production, that stark illumination... almost unsettling given the context. The deep shadows and intense light pinpoint certain areas. A moment frozen just before... Curator: The medium of engraving really emphasizes that dramatic contrast too. The process involves meticulously carving lines into a metal plate, applying ink, and then pressing it onto paper. It’s a laborious and highly skilled craft, each line dictating how light and shadow will eventually appear. And the distribution of labor would’ve been very divided on a project like this. Editor: You can almost feel the weight of the labor. Speaking of feeling, there's also a raw emotional energy; betrayal hangs heavy. That gathering storm brewing indoors mirrors that ominous moon shining outside. There's something intensely private playing out. It almost feels claustrophobic. Curator: Well, remember that prints like these circulated widely. The democratization of images allowed for ideas, even revolutionary ones, to permeate society more rapidly than ever before. Religious scenes like this, produced in multiples, brought theological concepts to broader audiences. Also, that focus on linear perspective became a technique and trope onto itself to create depth for increasingly more secular patrons of art. Editor: A crucial detail. It's odd how accessible and relatable their emotions become via distribution to private ownership. I am quite drawn to those faces - I see such complex states there... fear, certainly denial and dread... you are able to read into it intimately even while feeling distanced as the viewer. It makes it strangely potent. Curator: And it underscores the inherent contradiction, doesn't it? Art, even when dealing with faith, became a commodity, circulating in increasingly capitalist markets. This particular print showcases how devotional images became part of a larger system of production and consumption. Editor: True, and yet, the vulnerability on those faces transcends commerce. They bring something human out of the divine narrative; almost too good to be sold so commonly, it’s moving and perhaps even a bit haunting, given that history and distribution of its images. Curator: The image’s narrative power then isn't simply due to its artistic merit, but rather how the mode of its production helped establish the themes so ingrained into western popular imagination to this day. Editor: A fitting observation to appreciate an era defined both by expansion and contraction—a tension echoing still within those expressive eyes today, through time and all those mechanically produced.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.