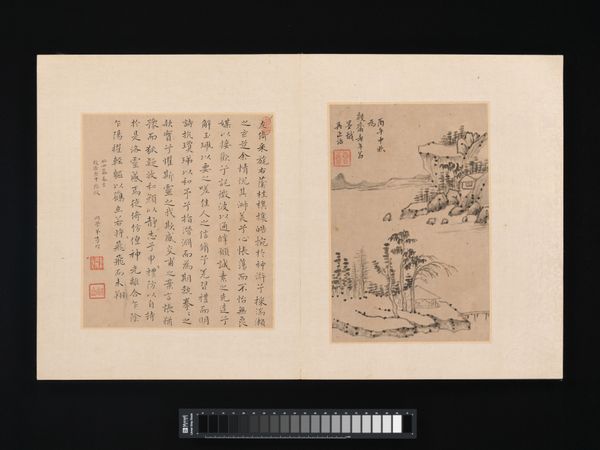

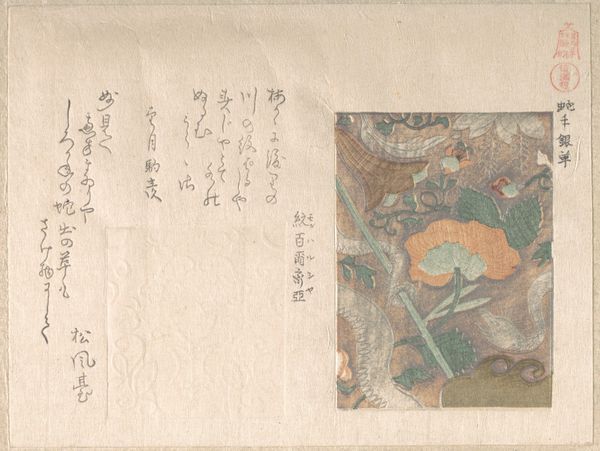

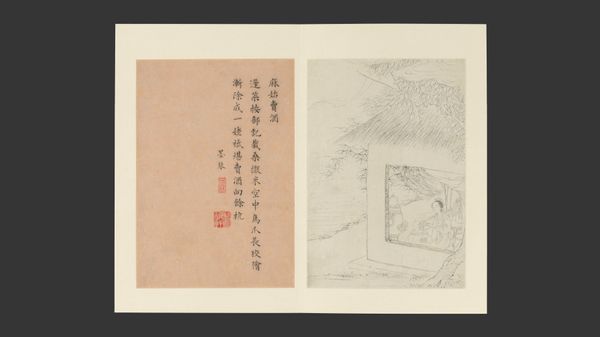

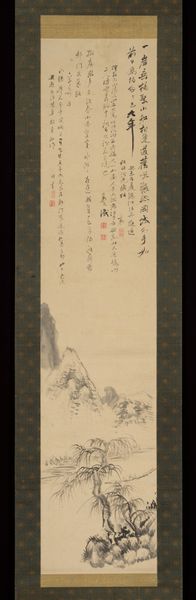

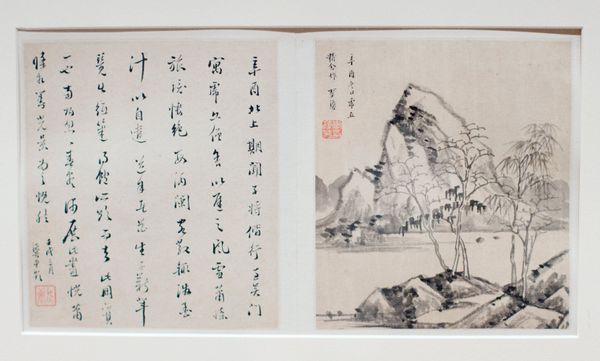

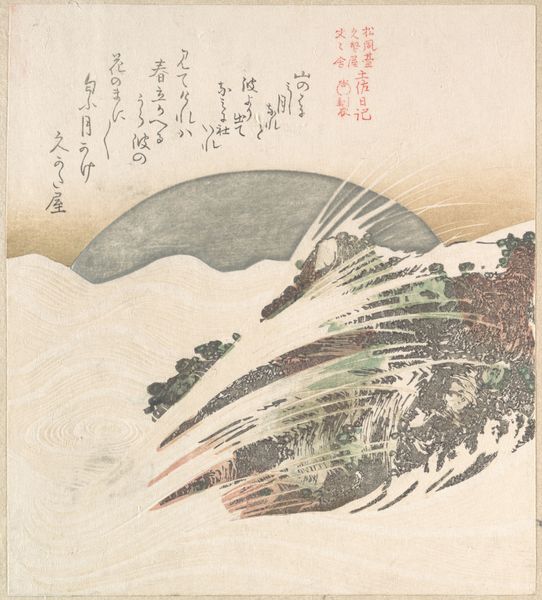

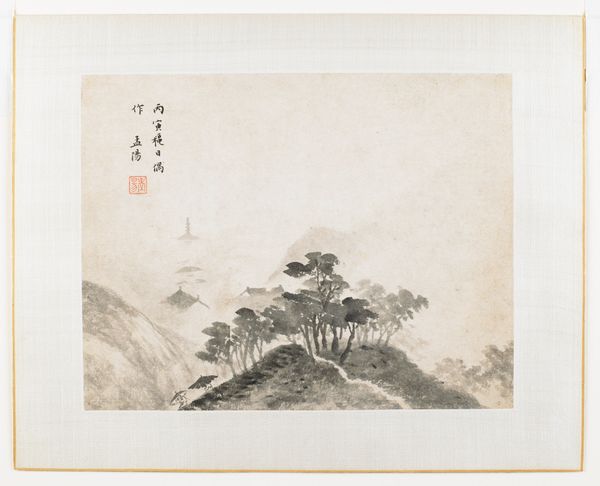

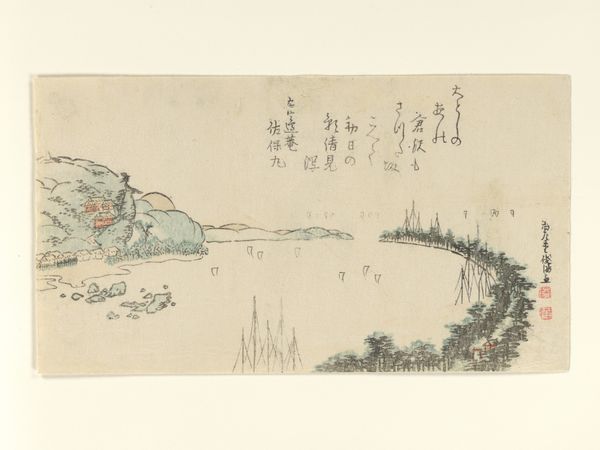

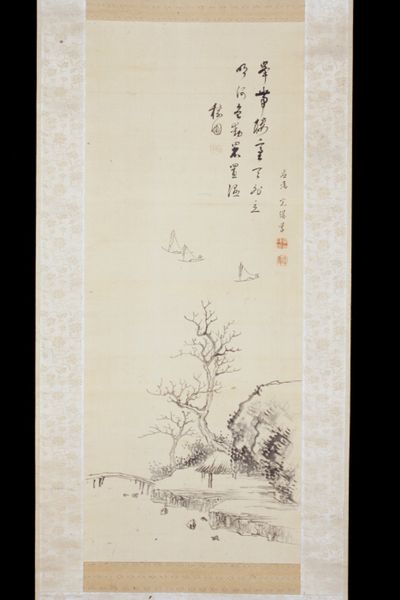

"Convenience in Drawing Water" from Jūben (Ten Conveniences); "Pleasure of Dawn" from Jūgi (Ten Pleasures) 1800

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: Image (each leaf): 7 3/8 × 7 5/8 in. (18.8 × 19.4 cm) Each album: 9 5/16 × 8 11/16 × 15/16 in. (23.6 × 22 × 2.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have “Convenience in Drawing Water” and “Pleasure of Dawn,” two drawings by Totoki Baigai from around 1800. They're done with ink, in a style reminiscent of ukiyo-e landscapes. I am intrigued by the interplay between the visual scene and the prominent calligraphy. What do you make of that juxtaposition? Curator: That's a crucial observation. Think about the relationship between image and text, and who had access to them. The calligraphy elevates the piece beyond a mere landscape; it suggests an engagement with a literati culture accessible only to a select, educated elite. Consider the social hierarchies embedded in who could 'read' this artwork on multiple levels. Editor: So, it’s a landscape, but also a status symbol, right? Curator: Exactly! But go deeper. How does the content of the calligraphy—perhaps a poem, or commentary—interact with the scene depicted? Is it reinforcing existing power structures, or subtly critiquing them? How does the visual representation of nature in Ukiyo-e mirror or question the philosophical concept of nature during the Edo period, and were those philosophies exclusive to certain genders, classes, or ethnic groups? Editor: That adds a whole new dimension. It’s not just about pretty landscapes, but about power, knowledge, and access. Thanks! Curator: Indeed. By unpacking these layers, we begin to see how seemingly simple artwork reflects complex social and political realities, offering us insight into the construction of identity and privilege.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.