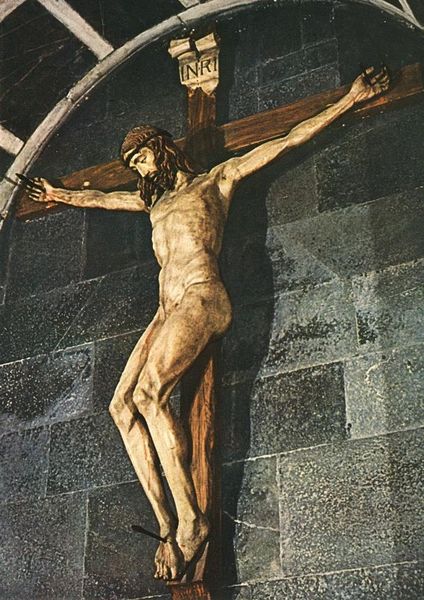

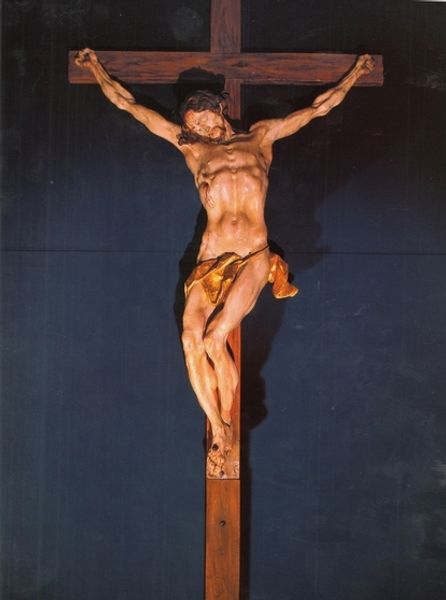

sculpture, wood

#

sculpture

#

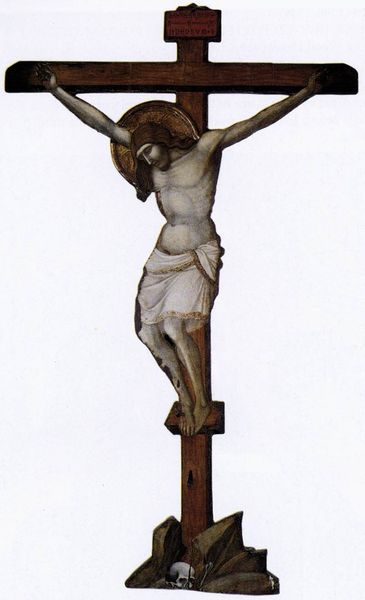

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

sculpture

#

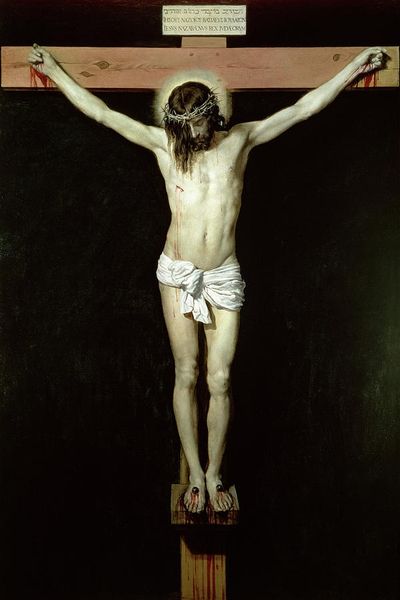

christianity

#

wood

#

crucifixion

#

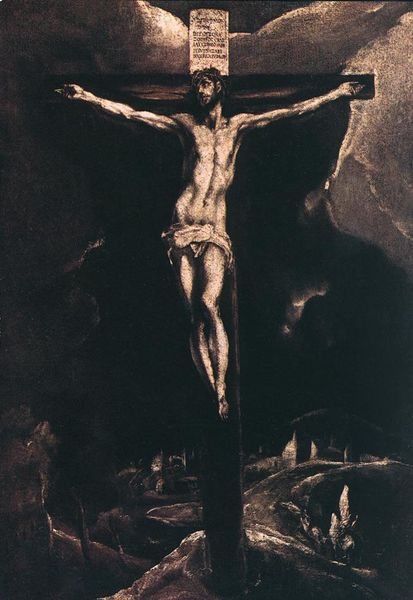

history-painting

#

charcoal

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

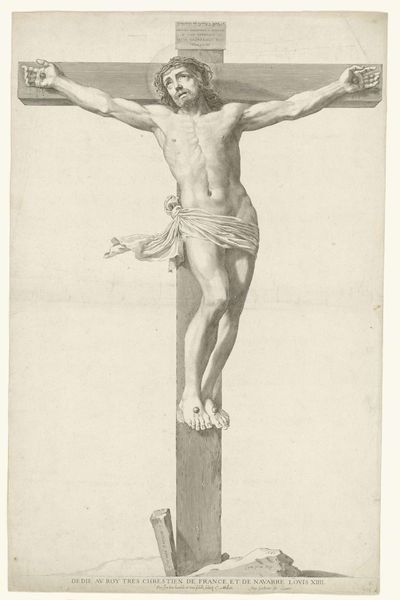

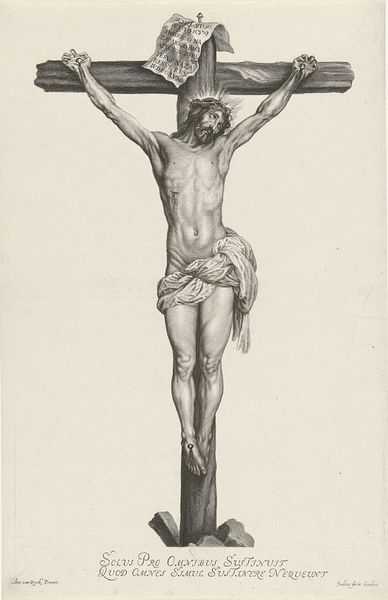

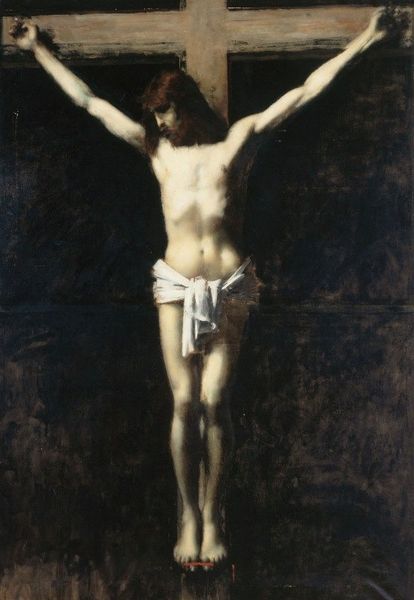

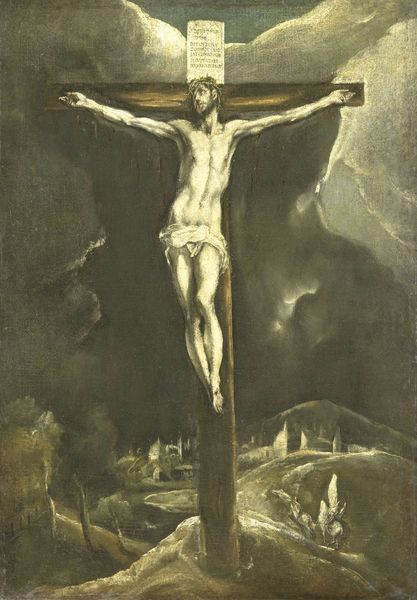

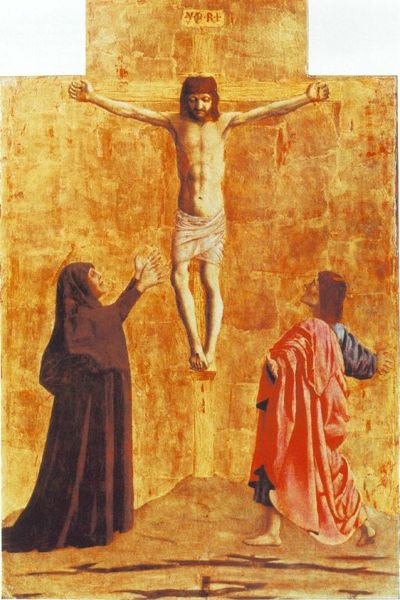

Dimensions: 142 x 135 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Well, immediately what strikes me is the raw vulnerability of it all. He's so exposed, isn't he? It’s less about glory, more about…suffering. Editor: Indeed. What we have here is Michelangelo's wooden sculpture, "Crucifixion", dating back to 1492 and currently housed in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. Let's delve into the artist's choices here. Curator: Wooden sculpture in Italy, 1492, the feeling, you can't avoid how unusual the nudity is. There’s this push and pull—spiritual significance with the shock. Editor: Precisely. Michelangelo uses the nude form not as a celebration of the classical ideal, but as a conduit for empathy, focusing on anatomical realism to convey human suffering. The twist in the torso, the subtly strained muscles, speak volumes about weight and strain. Curator: The texture too, you know? Rough, unfinished…like life itself. He embraces that imperfection, which for me, adds such emotional punch. There's nothing idealised here. He shows us that there’s beauty and terror at that place in life that feels both so perfect and terrible. Editor: From a formal perspective, the sculpture has a striking balance of vertical and horizontal lines, reinforcing the symbolic gravity of the crucifixion. The darkness of the cross, in contrast to Christ’s pallid figure, drives home the gravity. The grain of the wood adds a layer of meaning, underscoring the materiality of Christ's earthly sacrifice. It’s like every gouge and imperfection emphasizes that painful reality. Curator: The humanity of the moment really pierces through. How that rough wood becomes not a divine being removed from me but also completely approachable is where I fall apart at every great artwork. Editor: Ultimately, "Crucifixion" encapsulates the core Renaissance principles of humanism. It explores the depths of religious and artistic expression through careful design. It’s an eloquent example of semiotic intensity within form and space. Curator: It also reveals a truth about pain and empathy. Looking at Christ, a regular, pained human being, allows us to understand, relate and, perhaps, not feel so alone. And it shows us, even through suffering, that this feeling exists and is just a real.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.