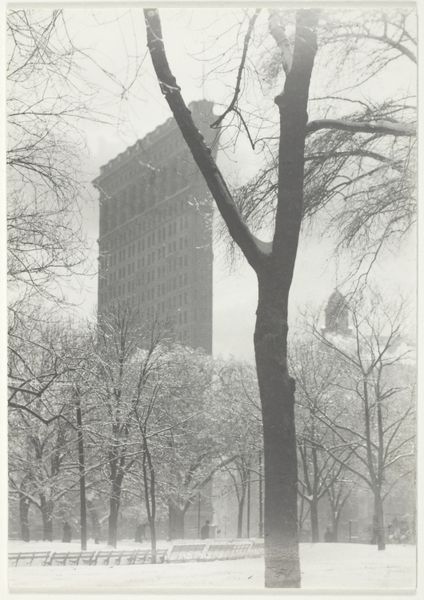

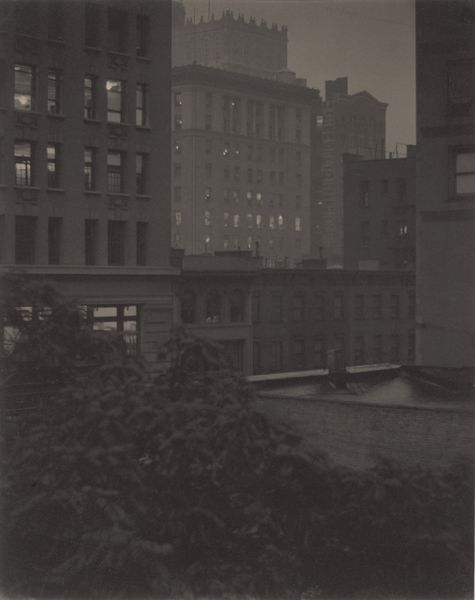

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 11.9 × 9.5 cm (4 11/16 × 3 3/4 in.) mat: 36.6 × 28.8 cm (14 7/16 × 11 5/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

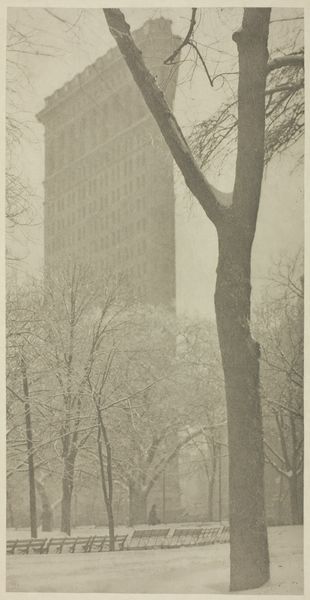

Curator: Here we have "The Flatiron," a gelatin-silver print possibly created between 1903 and 1932 by Alfred Stieglitz. Editor: The overall tone is muted and atmospheric. I immediately notice the texture of the snow against the rigid lines of the building and the organic shapes of the trees, emphasizing the materiality of the photographic print itself. Curator: It's interesting to see Stieglitz capturing this iconic skyscraper. Emerging in New York at the beginning of the 20th century, these new buildings signified modern progress, of course, but I feel like he's doing more here. His engagement with pictorialism sets the image apart. Editor: Yes, it moves beyond simple documentation. The way he’s framed the building through the trees transforms the urban landscape into something more…painterly. Did he manipulate the development process? The textures suggest a direct engagement with the materials, a labor intensive artistic decision. Curator: Precisely! This was a period when photography was fighting for its place as a fine art. The soft focus, the careful composition, and his printing techniques – all these elevated photography above mere mechanical reproduction and aligned it with painting. It's like he’s trying to tame the industrial revolution via soft-focus. Editor: Right, it challenges a strict divide between "high art" and crafted object. One wonders about the role of labor, access to darkroom technologies, the distribution of images as commodities in this era... Curator: The Flatiron Building, which became such a symbol, seems to float above the park in this version, divorced from the pressures of commerce, shaped by his artistic intervention rather than architectural innovation alone. Editor: So, we're seeing a deliberate layering, a translation through the photographic process that transforms industrial steel and glass into art. This shifts our attention not only to the skyscraper, but also to Stieglitz’s role as a transformative maker, an artisan if you will, using chemistry and light. Curator: It makes you reconsider not only photography's place, but also our very understanding of early 20th-century aesthetics. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing "The Flatiron" reminds us that photographs are never objective, they're carefully made material objects that contain implicit ideas about labor, social transformation, and artistry.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.