oil-paint

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

early-renaissance

#

portrait art

Copyright: Public domain

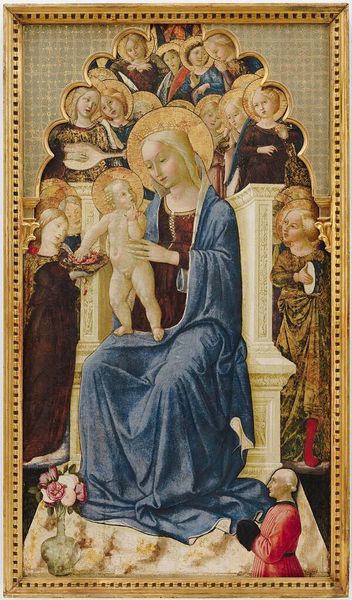

Curator: Look at this serene vision—"Maria mit dem Jesuskind vor der Rasenbank," or "Maria with the Infant Jesus on a Grassy Bench," painted around 1440 by Stefan Lochner. The medium is oil on wood. Editor: My first thought is the almost unsettling stillness. The Virgin’s gaze is averted, the child is static, and even the angels seem to hold their breath. What does this tell us about representations of motherhood during this time? Curator: The symbols speak volumes. The enclosed garden, the *hortus conclusus*, represents Mary's purity and virginity, untouched by the world. It’s a potent visual metaphor linking her to a divine, untouchable state. Editor: But let's consider the context of female agency then. Mary, as the mother of Jesus, occupies a uniquely powerful position, but this painting also confines her to idealized virtue and submissive spirituality, devoid of other societal agency, really. Isn't this idealized figure also a tool of power, reinforcing specific roles and expectations of women? Curator: I see your point. Yet, the faces and figures also feel intensely human. The softness in Mary’s face, and the chubby limbs of Jesus. Lochner brilliantly merges the celestial with the relatable, perhaps reflecting the hope that viewers could access divine grace. Editor: Indeed. The clustering faces of what appears to be the divine gaze—that chorus of male witnesses behind Mary—reinforces whose participation in grace really counts in this construction of social and religious relations. They're up there literally legitimizing the moment, overlooking the Virgin. Curator: Still, her stillness also presents her as powerful; the halos reinforce this with bright shining symbolic purity. She presides over this space. It speaks to the enduring symbolism embedded in artistic representation. The use of specific imagery—angels, halos, enclosed gardens—resonates through history. Editor: It certainly gives pause about how religious iconography intersects with politics. This painting isn't just beautiful; it's a cultural document rife with the assumptions and power dynamics of its era, demanding that we examine it with critical eyes. Curator: Exactly, art can act as an active archive of power, culture, and religion—making it both intensely human and also, something beyond ourselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.