Copyright: Unichi Hiratsuka,Fair Use

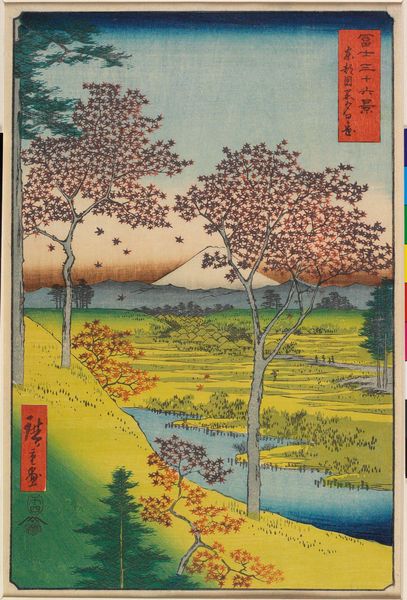

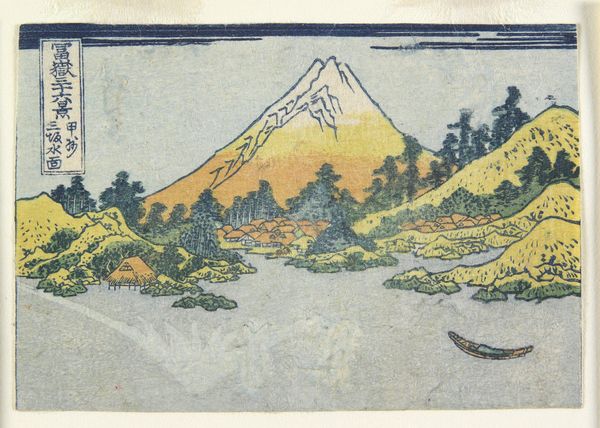

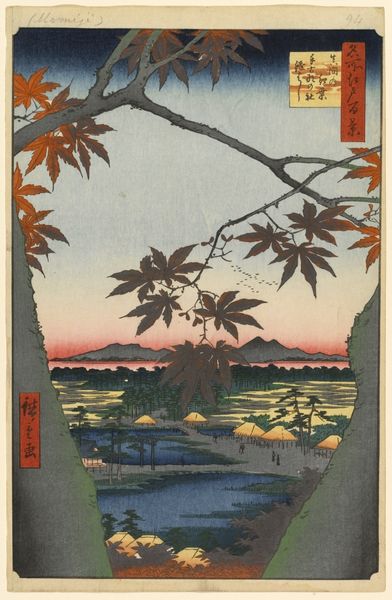

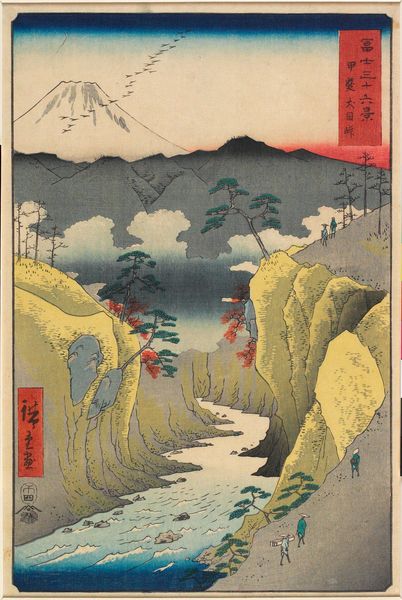

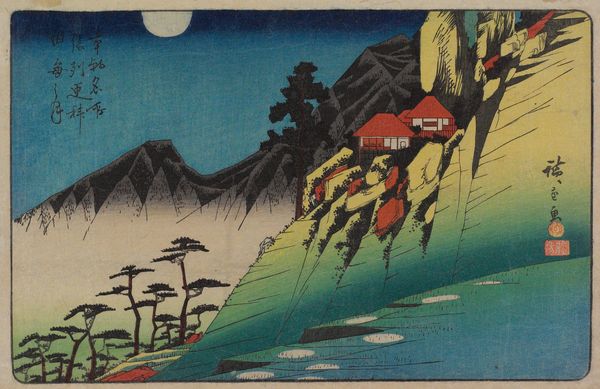

Curator: The first thing that strikes me is the bold, simplified rendering. The linocut technique really emphasizes the shapes and colors of this landscape. Editor: Yes, there’s a very graphic quality to it. This work is titled "Oku-Tama in Autumn," crafted in 1927 by Unichi Hiratsuka. The artist seems to have captured the essence of a specific location rather than aiming for strict realism. The peak in the background seems to evoke associations with Mt. Fuji and related prints in the Ukiyo-e tradition. Curator: It is interesting that Hiratsuka adopted linocut, a Western technique, for a subject deeply rooted in Japanese artistic tradition. He certainly gives the traditional landscape a jolt with this style. What’s most prominent to you in this image? Editor: The interplay between the sharp, angular rocks framing the river and the softer, rounded forms of the foliage draws my eye. The orange and green foliage—symbols of autumn's transient beauty, reminding us of time's ceaseless flow and the bittersweet nature of beauty. The river’s presence speaks of a cleansing renewal. I am really moved by that aspect in particular. Curator: Hiratsuka was associated with the Sosaku-Hanga movement, which advocated for the artist's complete control over the printmaking process, from design to carving and printing. This explains his distinctive style. It moved away from the collaborative approach common in earlier Ukiyo-e. Editor: This really has an element of spiritual contemplation for me, in how nature embodies powerful, ever-changing forces of renewal and temporality. Did the context in which Hiratsuka worked—the artistic or political scene—reflect on the symbolism behind nature? Curator: The Taisho and early Showa eras were a period of intense social and artistic change in Japan. Artists like Hiratsuka sought to express their individuality and reflect the changing relationship between Japan and the West through their art. It speaks of a longing for identity in a rapidly modernizing nation, something the landscapes in his art sought to encapsulate. Editor: Thinking about how landscapes reflect societal shifts certainly adds a whole new layer of meaning. Thank you. Curator: Indeed, looking at the Sosaku Hanga movement can help understand that the linocut landscape aesthetic should not necessarily be perceived as traditionally Ukiyo-e as the scene might imply.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.