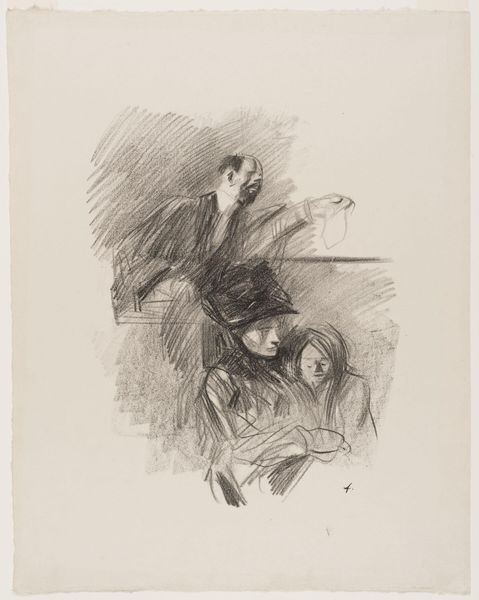

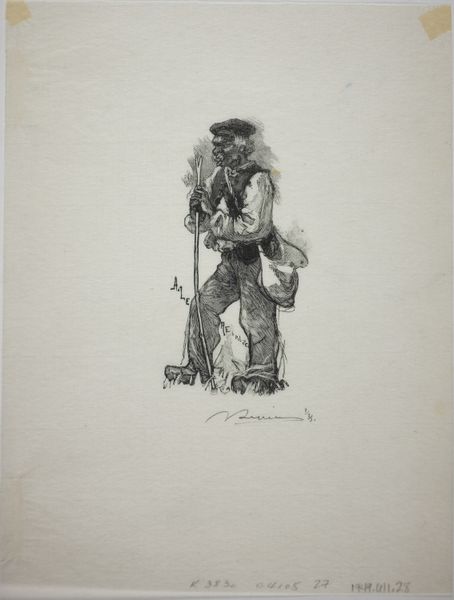

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

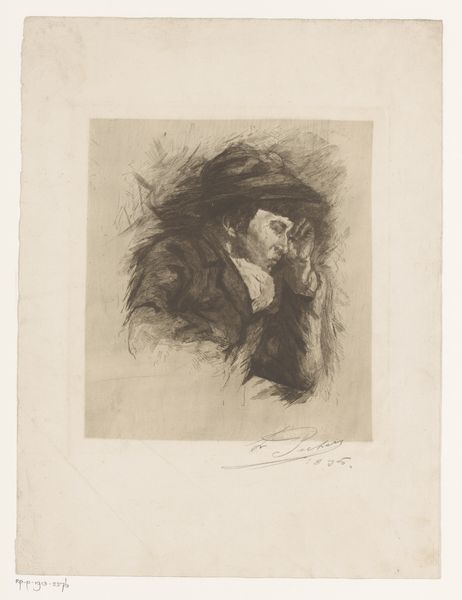

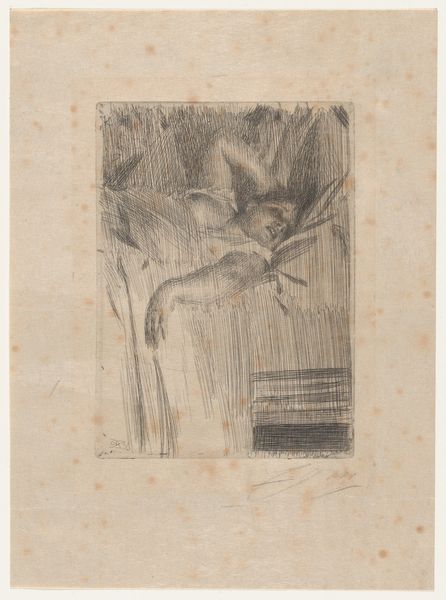

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

possibly oil pastel

#

paper

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

underpainting

#

france

#

watercolour illustration

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 88 × 42 mm (image); 204 × 155 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, we're looking at Auguste-Louis Lepère's "The Pass of the Seven Caverns," likely from 1908. It’s a print, an engraving on paper, currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It looks like a lone figure emerging from a shadowy opening, almost swallowed by the darkness. What strikes you about it? Curator: What interests me most are the *means* by which Lepère achieves this sense of confinement. Look at the layering of the engraving lines; it’s more than just depiction; it's the *labor* evident in the build-up of darkness, creating a palpable weight pressing down on the figure. How does this technique reflect the social context of printmaking at the time? Editor: Well, prints allowed for wider distribution, making art more accessible. Curator: Exactly! It wasn’t just about *what* was depicted, but *how* the art was produced and *who* had access to it. The figure almost disappears into the printing process. Does this challenge notions of fine art versus craft for you? Consider the role of the engraver—a skilled artisan reproducing an image. Where do we draw the line? Editor: I see what you mean. It questions the uniqueness we often associate with art. Instead, it’s about the skilled labor and reproduction… almost mass production. So, Lepère is not only presenting us with a scene, but also the idea of art *as* labor? Curator: Precisely. It’s about acknowledging the often-invisible processes behind the art object, reminding us of the hands involved in its making and its subsequent consumption. This is far more than just light and shadow. Editor: It gives me a different way of viewing not only this piece but any printed artwork. I’ll never look at an engraving quite the same way again! Curator: Indeed. And that's exactly the point. To think more deeply about materiality in production, reproduction, and dissemination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.