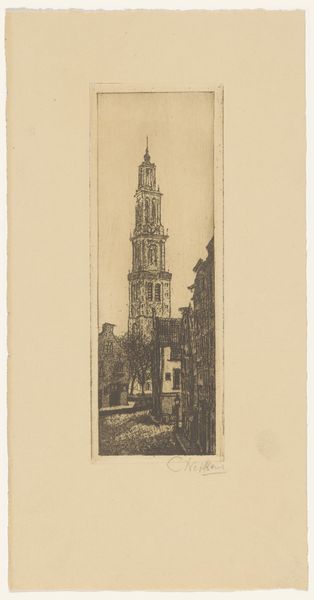

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

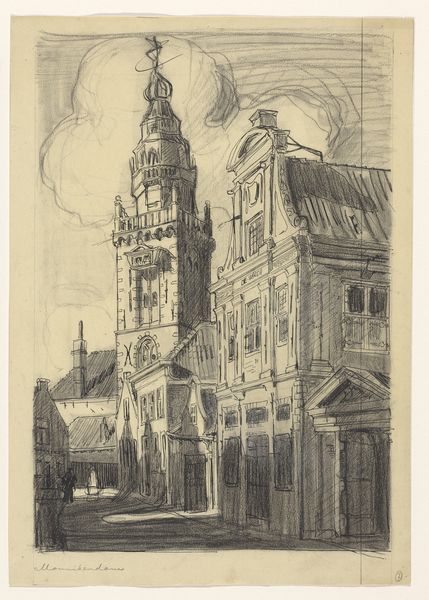

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

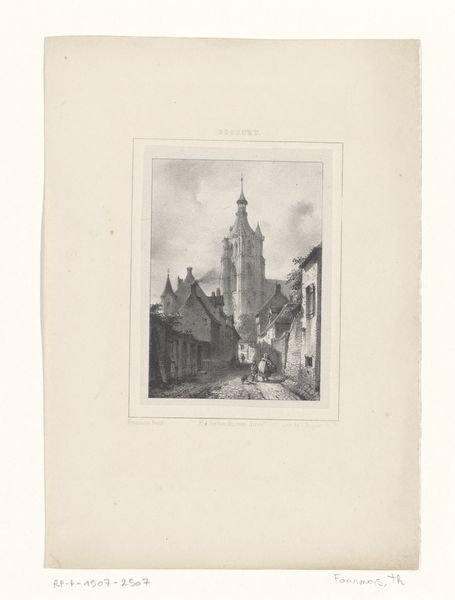

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

cityscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

street

#

realism

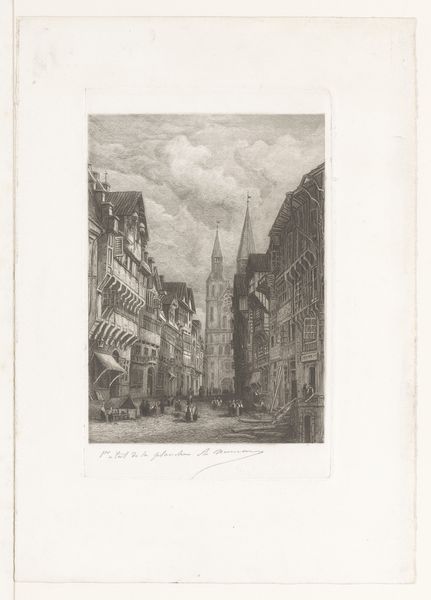

Dimensions: height 476 mm, width 271 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

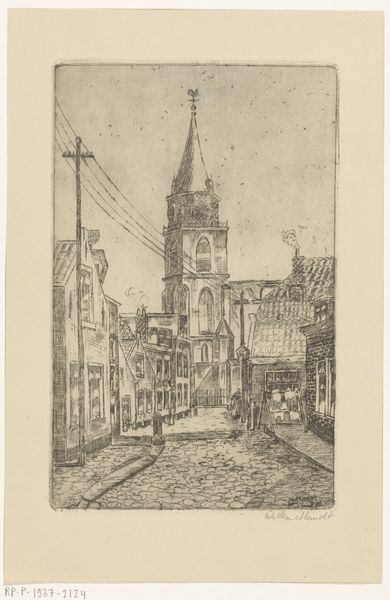

Editor: We’re looking at "Edam," an etching on paper by Willem Adrianus Grondhout, dating from 1888 to 1934. The overwhelming sense is one of quiet, quaint village life, almost frozen in time. What stands out to you about this print? Curator: I’m drawn to how the spire dominates the scene, really placing the church, and therefore religion, as central to community life. Think about the late 19th and early 20th centuries – a period of immense social and political upheaval. How might Grondhout be subtly commenting on the Church's role, either as a bastion of stability or a symbol of entrenched power? Editor: That’s interesting. I was just seeing the composition and how it guides your eye, but I didn’t consider the church’s symbolic importance in that era. Curator: And what about the figures depicted in the street? Are they merely picturesque details, or might they tell us something about the lived experiences of everyday people during that period? Notice the depiction of women, in particular. Editor: I see a few women, some with children. They seem… anonymous, perhaps representative of domesticity and daily life in this small town? Curator: Exactly. Consider how societal expectations confined women's roles largely to the domestic sphere. Does the artwork challenge or reinforce those norms? What does the artist's choice to portray them this way tell us about his perspective, and perhaps the prevailing societal views? Editor: I suppose it’s easy to overlook the potential commentary on gender roles. I initially just appreciated the “snapshot” quality of the scene, without considering the underlying social dynamics at play. Curator: Precisely! Art isn't just about aesthetics; it's a reflection of the power structures, ideologies, and lived realities of its time. Considering these interwoven narratives opens up a much deeper understanding. Editor: I’ll definitely look at these scenes in a new way from now on, paying closer attention to what they reveal about social context. Curator: And that, ultimately, is how we make art history relevant, by constantly questioning and situating these works within larger dialogues.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.