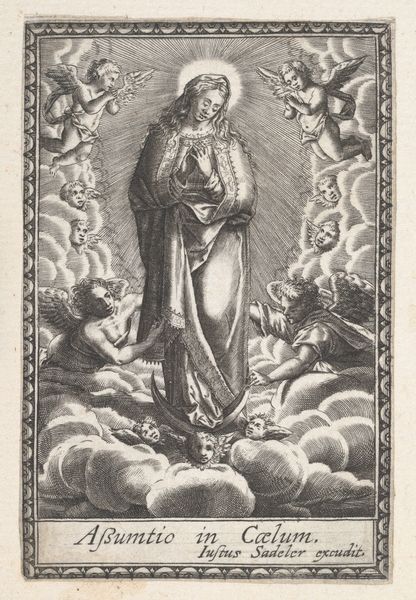

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

# print

#

figuration

#

madonna

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 109 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, made sometime between 1500 and 1525 by an anonymous artist, is titled "Madonna on the Crescent Moon". The Virgin Mary stands holding the Christ child, surrounded by angels. What strikes you first about this print? Editor: There’s a dreamlike quality to it. It's serene, yet the lines create such defined shapes. I'm drawn to the figure of the Madonna as it reflects societal constraints of the time and how femininity was seen through the religious narrative. Curator: Precisely. Notice how she's placed on the crescent moon, surrounded by a mandorla of light? It is evocative, tapping into an ancient visual language. The moon, long associated with the divine feminine, speaks to cycles, to change. We see echoes of goddesses in her portrayal. Editor: It is more than an echo, it’s appropriation and recontextualisation. Earlier, powerful symbols associated with female divinity were repackaged under a patriarchal system. Her demure gaze is no accident, nor is the infant she’s burdened to bear for mankind’s redemption, a visible claim on her agency. Curator: But what about the radiant light and the joyful cherubs? This isn't just about oppression; it also embodies triumph and divine grace. Light, symbolically, cuts through darkness, offering hope through the mother and child. Those musical angels are joyous, after all. Editor: Absolutely. And it is critical to consider who that image served and its effects within that time. Were they images of liberation for women, or images deployed as subtle weapons, framing female experience to the exclusion of full humanity? How were images weaponized? Curator: It’s a fascinating dance, this interplay between hope and control. To appreciate the artwork’s depth is to acknowledge both elements are entwined. Look closely at how those sharp lines work against the light creating depth—an incredible technique from that period. Editor: By putting these images into conversation with contemporary discourse, we encourage viewers to interrogate not only the art, but themselves. The questions are not about beauty alone, but also power, gender, and historical agency. Curator: So we witness beauty, but acknowledge the subtle social commentary it reflects. It shows the layered historical narratives beneath such images. Thank you for offering those perspectives. Editor: My pleasure. Art should spur this vital, ongoing conversation, regardless of period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.