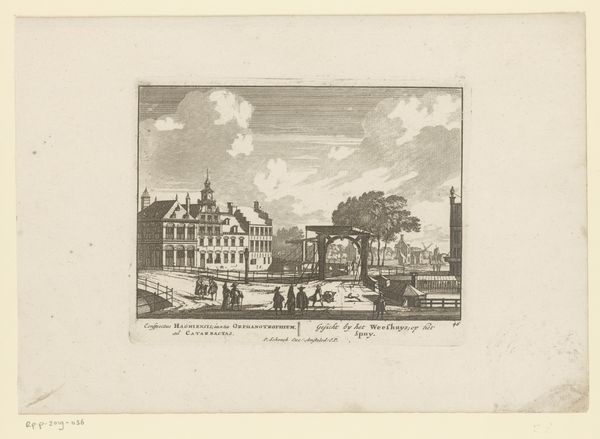

print, etching, engraving

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 273 mm, width 365 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Gezicht op het Gildehuis der Vrije Schippers en De Graslei," an etching by Henri Borremans, created sometime between 1822 and 1844. It has this lovely old engraving style, and I’m immediately drawn to the detailed depiction of daily life against the backdrop of these striking buildings. What catches your eye about it? Curator: I’m fascinated by how Borremans' print serves as both a picturesque scene and a social document. The “Gildehuis,” or Guildhall, wasn’t merely a building; it was a nexus of economic and social power. Notice how the architecture broadcasts that power, meant to inspire and maybe even intimidate. Editor: Intimidate? In what way? Curator: Well, think about who controlled the production and dissemination of images like this. These prints circulated amongst a specific, likely affluent, audience. They reaffirmed a certain social order, visually legitimizing the authority of the guilds and the established elites within Ghent. Look at how much space is devoted to the architecture versus the working figures in the foreground. Who is the focus here? Editor: You're right, the building dominates! But what about its artistic intention? Curator: Borremans likely intended to cater to the Romanticism of the era. Cityscapes became vehicles for evoking nostalgia and civic pride, subtly promoting bourgeois values. It presents an idealized version of Ghent’s past, conveniently glossing over any social tensions of the time. Editor: So it’s less about capturing reality and more about shaping a particular narrative about the city. Curator: Precisely! Understanding this context allows us to see beyond the beautiful etching and to unpack the power dynamics it subtly encodes. Editor: That’s given me a completely different lens through which to appreciate this work – considering not just *what* it shows, but *who* it’s really for and *why*. Curator: And the narratives it perpetuates, often without explicitly stating them. That's the real work of art history, isn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.