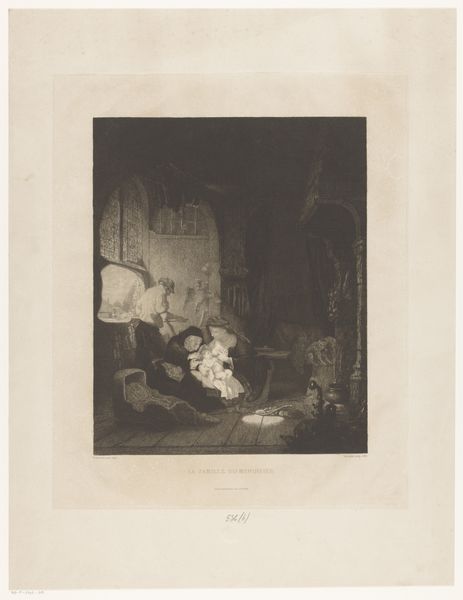

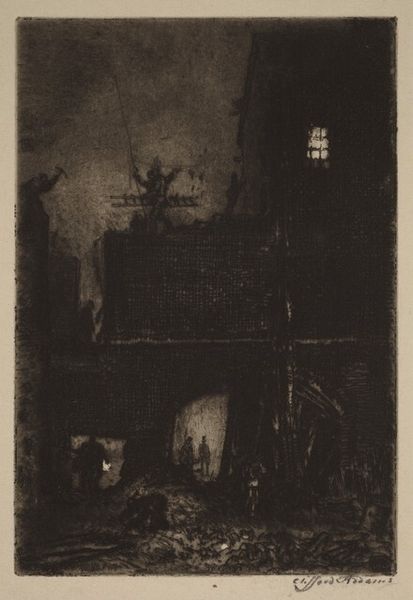

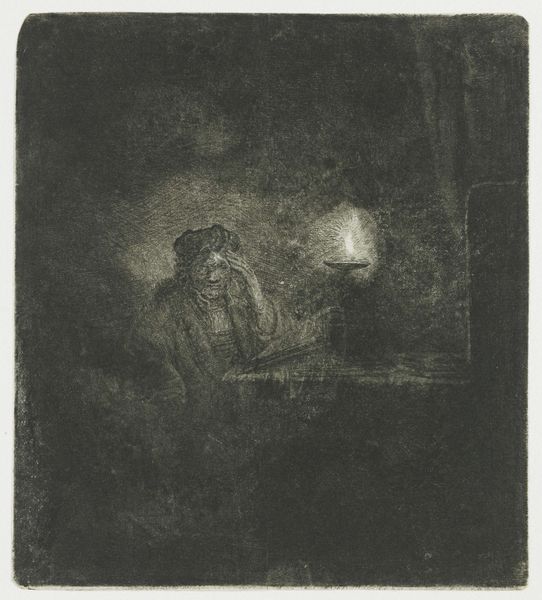

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

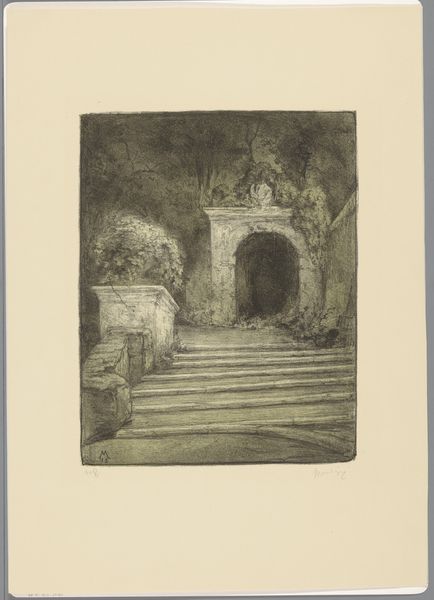

drawing

#

girl

# print

#

etching

#

boy

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

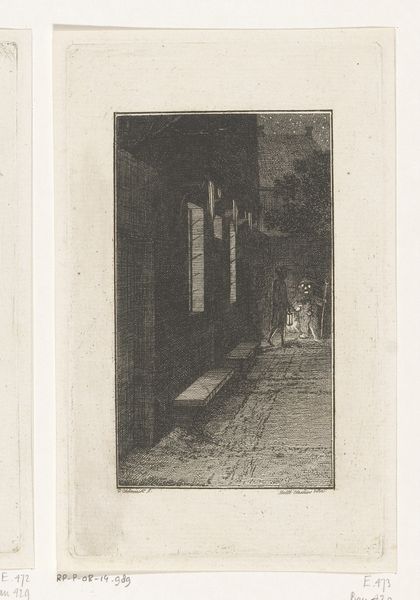

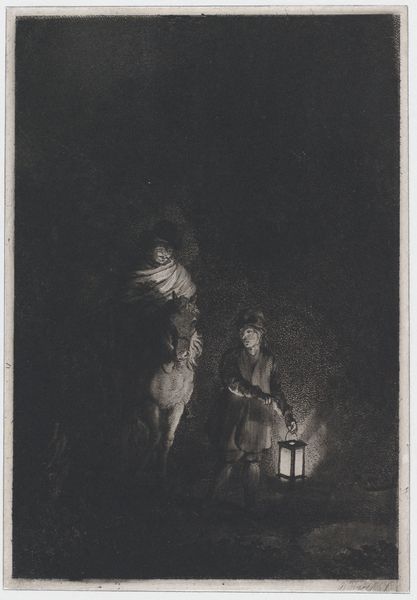

Dimensions: Sheet: 8 7/8 × 6 11/16 in. (22.5 × 17 cm) Image: 5 1/2 × 4 3/16 in. (14 × 10.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

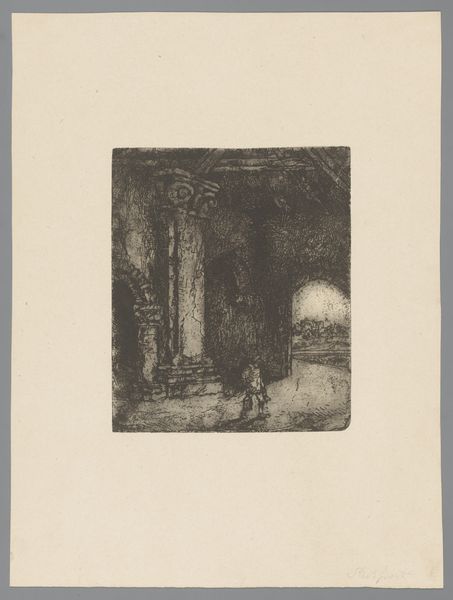

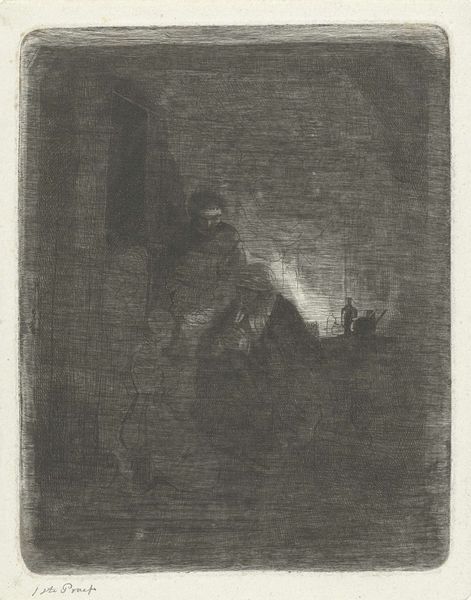

Curator: Here we have Jean-Baptiste Isabey's "Children Holding a Candle in a Church," created in 1818. This captivating scene resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It's quite evocative, almost like a dreamscape. The heavy use of shadow emphasizes the light from that single candle...makes you feel like you're eavesdropping on a secret. Curator: Indeed. Isabey's work often touches on the intimate and familial. In post-Revolutionary France, artists increasingly turned to domestic themes. The church setting provides a stark backdrop for the innocent intimacy of these children. Editor: An etching, isn't it? I wonder about the plate. It looks like the work focuses less on an "ideal" Romantic form, more on capturing a fleeting sense of light through texture on the surface, achieved, laboriously, of course, by many hands. Curator: The print medium allows wider dissemination, furthering the artwork's sociopolitical impact. History painting often dealt with grand state matters. A scene like this presents an intriguing, private perspective on the individual's relation to societal structures such as the Church. Editor: It makes me consider, though, where the labor actually resided. Someone had to prepare the copper, mix the acid...it's a commercial piece in the end. What did "originality" really mean when production required so much collective effort? Curator: It invites many questions. Think of it as a challenge to prevailing academic artistic standards during that era, paving a path towards more democratized forms of art, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Possibly, but democratization involved the hands of those producing it. It really wasn't about the *art*, was it? These prints went everywhere. It is more an artifact of industrialization and social change—commodification for the rising bourgeoisie— Curator: True. It offers an intriguing lens to understanding shifting roles for both artistic subject and observer. The candlelight beckons us in—an invitation to connect, or a warning to observe from afar? Editor: All art eventually boils down to a commodity, doesn't it? Curator: Well, the painting gives us an entry point to think about that connection as more and more art shifted to mass production and consumption in that period. Editor: True...a small, but valuable portal into considering larger shifts and systems at play during the nineteenth century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.