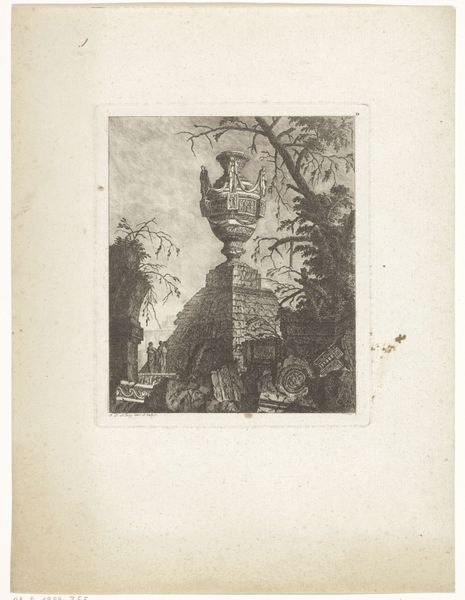

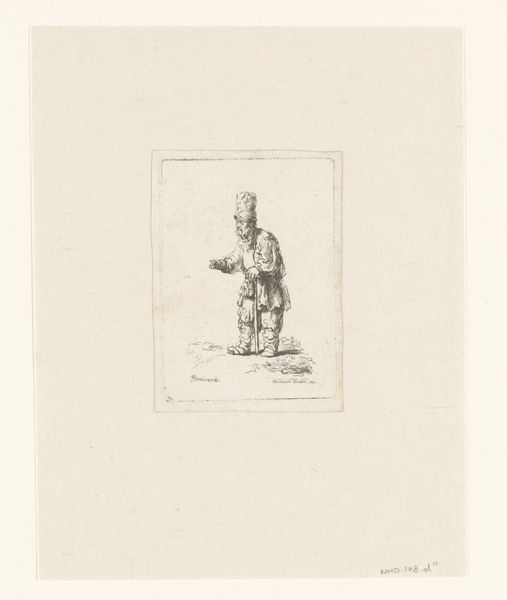

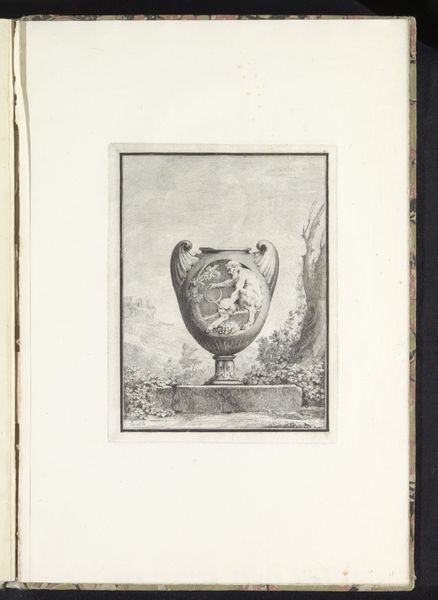

drawing, print, etching, paper, pen, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

engraving

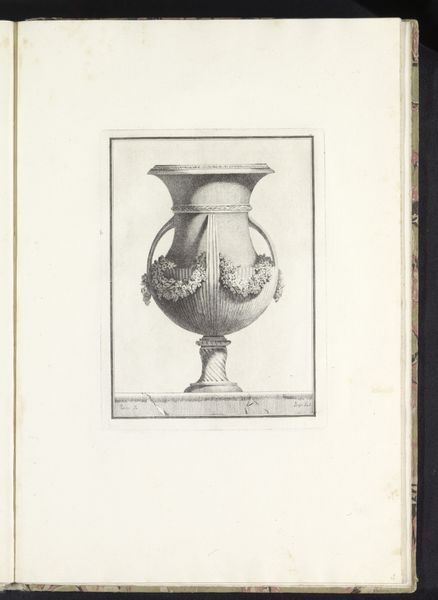

Dimensions: height 223 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

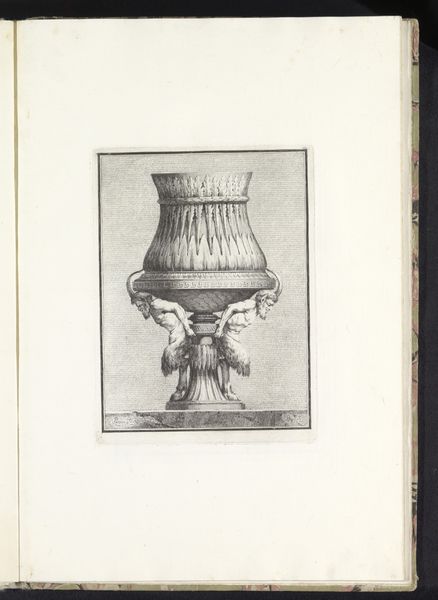

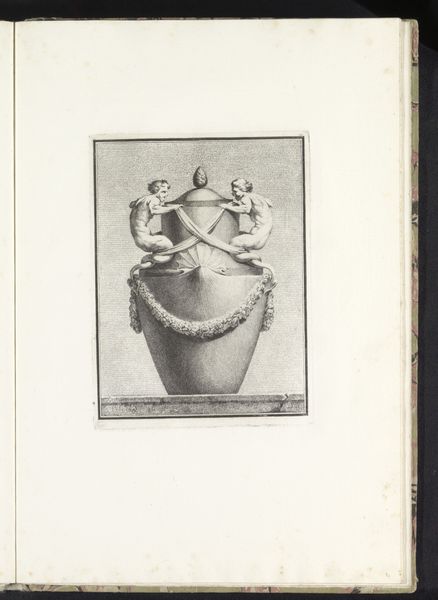

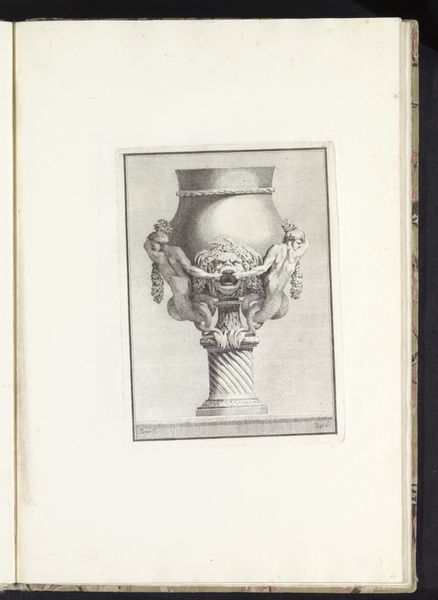

Curator: Benigno Bossi created this etching and engraving around 1764, titled "Vaas in een landschap met aquaduct", now held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels like a quiet meditation on decay, doesn't it? That classical urn, dominating the scene, feels both monumental and fragile against the backdrop of that crumbling aquaduct. Curator: Bossi was working in a time captivated by the picturesque, but he presents a somber grandeur, reflective of shifts in artistic taste away from the Baroque excesses toward a more austere Neoclassicism. Consider the social conditions encouraging these tastes; a rising mercantile class perhaps seeking status and sobriety. Editor: Right. It’s all in the meticulous details of the etching. You see the fine lines giving the stone its texture, almost mimicking the craft of actual stone carving, yet replicated through the printing press for wider distribution and consumption. Did this alter its meaning or artistic value? Curator: Certainly. Printmaking allowed for wider dissemination of aesthetic ideas, impacting artistic movements and tastes beyond the elites. This print, through its reproducibility, democratizes, to a certain extent, the consumption of classical ideals. But we should acknowledge its exclusivity. These were, after all, luxury prints for collectors. Editor: I find myself thinking about the laborers involved in quarrying the original marble, those who built and destroyed the aquaduct, versus Bossi who conceived and executed this print, and even the printing press operators that further multiplied the image through labor. Are these parallel acts of creation? Curator: That's a provocative parallel to draw. We often silo artistry into these categories - "high" art, and "mere" craft - when, as you've indicated, the labor involved in creating, disseminating, and even consuming such art involves layers of workers and cultural values. Bossi likely intended this as a contemplation of the passage of time and the weight of history, an illustration of classical taste- and these all intertwine within production processes and the final reception of his images. Editor: Considering these details allows for a reading less about a singular artistic genius and more about systems of production and valuation. Curator: Precisely, the image itself is as much a historical record as it is an artistic creation. It acts as a mirror reflecting how society in 1764 engaged with its own classical past. Editor: It's fascinating to see how analyzing an image this way opens up not just its artistic components but its embedded social framework as well. Curator: Indeed. There's a constant conversation to be had.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.