drawing, paper, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

genre-painting

#

charcoal

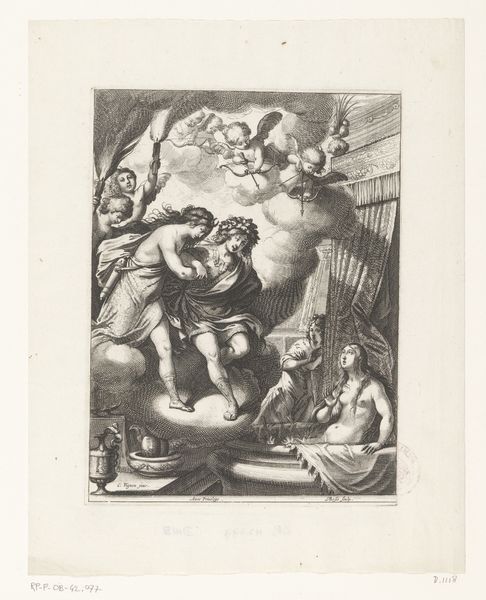

Dimensions: height 302 mm, width 222 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

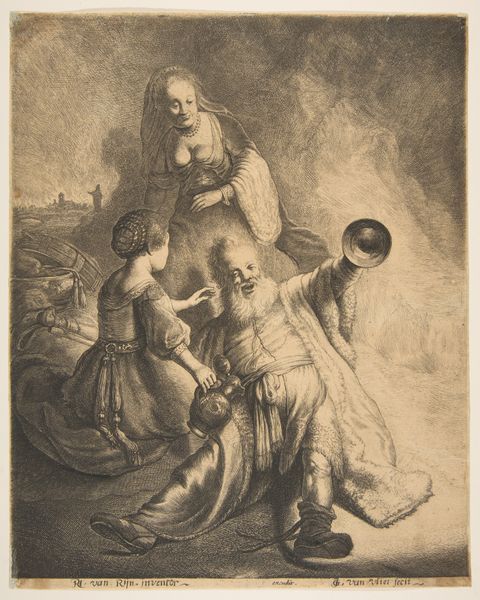

Curator: Moses ter Borch's "Lot and His Daughters," created in 1661, depicts a dramatic biblical scene using charcoal and pencil on paper. It currently resides at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Whew. It has this overwhelming sense of foreboding, wouldn’t you say? Like watching a storm gather in the distance. The expressions feel heightened, desperate. It feels feverish to me, unsettling to behold such moral dissolution with such, shall we say, 'casual' attire? Curator: The choice of charcoal and pencil is interesting here. These accessible, almost humble materials, amplify the narrative's grounded nature, which can speak to the availability of such art forms at this moment in history. It shifts from the rarefied oil paintings and luxury materials towards printmaking that allowed for broader distribution and more public access to potent imagery. Editor: Precisely! See, for me, it echoes those blurry edges in memory, or a dream rapidly fading. What materials allow you to take away—charcoal being essentially burnt matter, speaks so intensely about destruction, both of a city and of moral constraints here. It does mirror the biblical scene beautifully. I even want to claim they almost smell like the fires in the city it reflects... a little dramatic, I know. Curator: That is exactly the strength here: the direct connection between material and subject, highlighting how a specific medium choices influence viewers. Ter Borch uses chiaroscuro dramatically, obscuring details, shifting focus between narrative, and even suggesting class mobility between more common materials than fine paints or metals, offering critical insight of social upheaval that echoes this dramatic Biblical moment. Editor: Right, it’s like the technique itself embodies the themes. One can imagine Ter Borch really engaging, the smudging— the covering, hiding, a deliberate choice. Maybe a material choice speaks to hiding Lot from himself! Curator: So it is then more than mere artistic intention, it’s the cultural implications the image takes on as result of process and product, right? How it operates as vehicle to broader conversations within art itself? Editor: Right you are. Ter Borch delivers not just a dramatic tale, but uses material production in accessible, almost ‘burnt remains’— as a way into the soul. Curator: And it is this interplay, of technique and broader social access, that is the crux of engaging critically with an image and cultural artifact as historically meaningful as Ter Borch. Editor: Indeed. Thank you for bringing those considerations into the picture, literally.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.