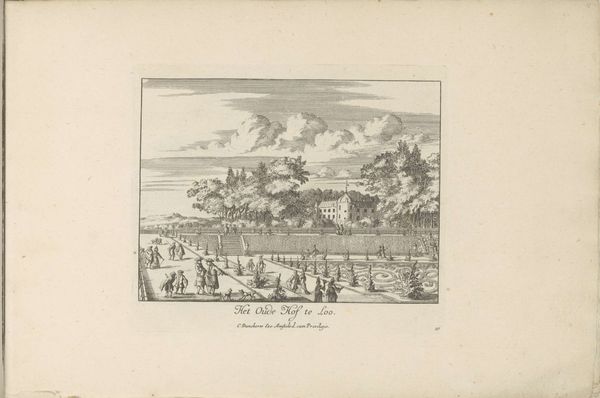

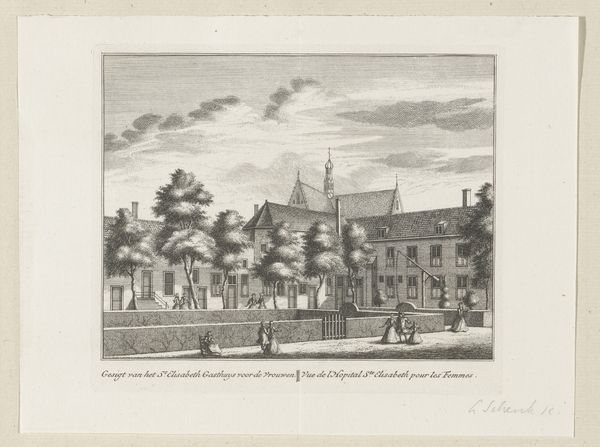

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 141 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s take a look at “Stables at Paleis Het Loo,” a print and drawing by Cornelis Danckerts the Second, created sometime between 1696 and 1718. What do you see? Editor: At first glance, a sense of serene order. A very tidy streetscape rendered in meticulous detail—though that sky seems about to swallow everything up! Is it just me, or is there something slightly unsettling amidst all that tidiness? Curator: It's interesting you pick up on that. On one level, it functions as a very conventional city view, showcasing the architecture and perhaps, suggesting the power and order of the court. The artist is documenting, promoting even. Editor: But then, there are those tiny figures in the street...strangely theatrical. They’re arranged with the drama of a stage play. And the stables, lined up so perfectly—it almost feels less about horses and more about power structures. You sense the controlling hand of landscape design at work, the buildings lined in a rigid order. Curator: Precisely. The rigid order reflects a time obsessed with control, with presenting a flawless image of authority and divine right. Think of Versailles, on a slightly smaller, Dutch scale. It speaks of enforced social harmony as an artistic feat. The baroque ideal in material form. Editor: Right, this isn’t just a nice street view; it's a carefully constructed projection. The artist wasn't merely capturing reality; they were participating in building and reflecting a very specific ideology. The realism is carefully curated, and more contrived than at first it looks! Curator: Consider the medium as well: printmaking, intended for wide distribution. This image was meant to be seen, circulated, digested as a form of propaganda, of sorts, solidifying the image of the Dutch court. Editor: It really shifts my perspective. From seeing a pretty architectural study to realizing how implicated it is in systems of power, ambition, and even, if only gently, coercion. Thanks! Curator: Indeed. Sometimes the quietest images are the loudest communicators of historical and social contexts. That's where its impact lies for me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.