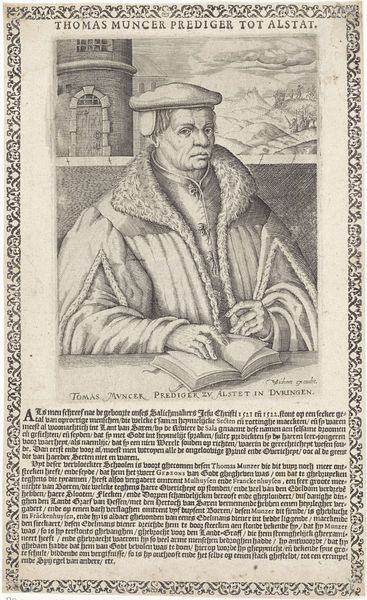

engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 294 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

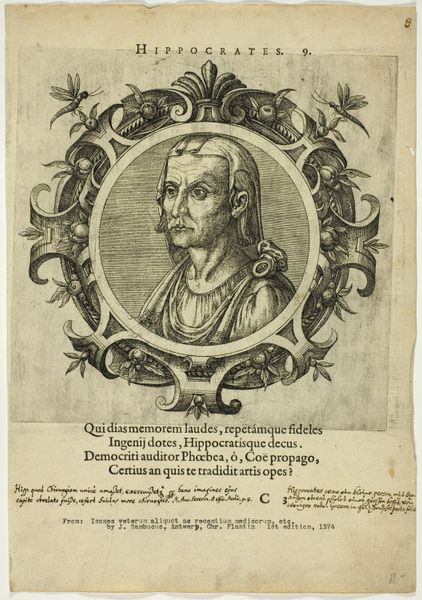

Curator: The engraving we are viewing is entitled "Portret van Karel van Egmond," dating back to 1639 and created by Paul de Zetter. It's a striking example of Dutch Golden Age portraiture. Editor: My first impression is somber; the figure looks burdened, weighed down by his opulent garments and the stern gaze that pierces through time. Curator: Indeed. De Zetter uses the line to incredible effect here. Note the intricate detailing of the fur collar, the precise rendering of facial features. There is such clarity and purpose within each stroke. The use of Latin text acts as an inscription around the oval, monumentalizing the figure. Editor: I'm curious about that inscription. The phrase "Carolus Egmondanus D. G. Dux Gelriae" certainly declares his noble status – Charles of Egmond, by the Grace of God, Duke of Guelders. Considering the context of the Dutch Golden Age, wouldn’t this portrait and its Latin inscription have been laden with complex political meanings regarding power, and perhaps, even resistance? How might viewers in 1639 have perceived the Duke, whose image is enshrined by the humanist lettering? Curator: I agree. The very form suggests a return to classical ideals. The sharp, clean lines used to portray him grant him the grandeur we associate with depictions of Roman emperors and thinkers. Notice the hands. The Duke is presenting, holding the carnation – a symbol of love and loyalty – to the viewer, asking us to admire him, even adore him. This is a testament to De Zetter's ability to capture and convey social standing through mere material and compositional elements. Editor: But doesn’t it also make the image and its commissioner complicit? To what extent can the engraving and its technical virtuosity obscure a complex relationship to history? Charles of Egmond had lost the battle to maintain control over his territories, no? How much power could this portrait still possibly communicate? It seems more of an artifact that illustrates the remnants of bygone power, especially because prints circulated through the burgeoning art market. How do we begin to historicize this circulation? Curator: Your questions expose inherent paradoxes, and underscore how powerful visual art can become. Perhaps we can admire both the construction of Charles’ representation and continue to unpack all the contextual material that makes this image come to life! Editor: Yes, and as such, this work asks us to reflect on our present relationship to this history that always threatens to escape from the surface of art, isn't that right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.