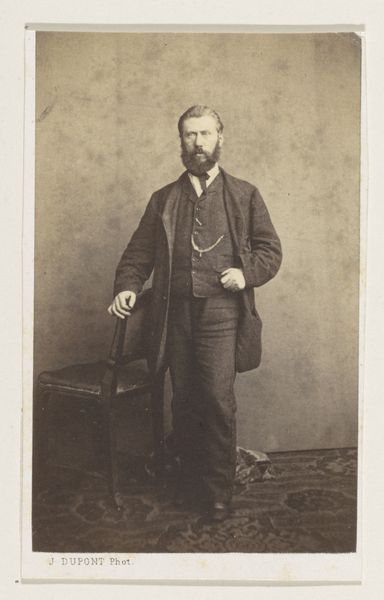

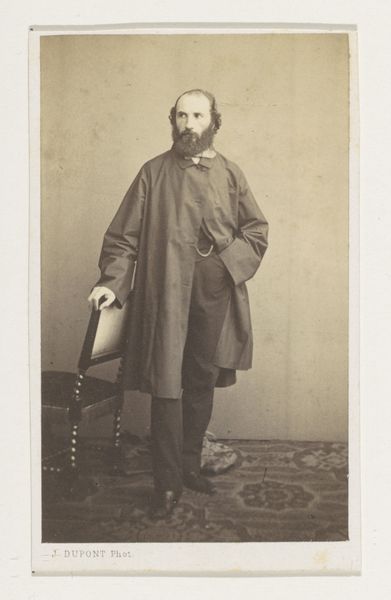

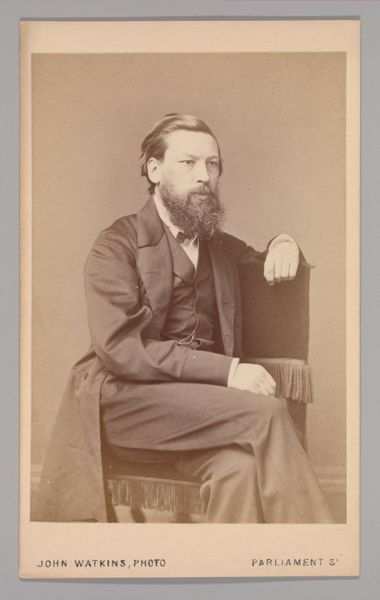

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

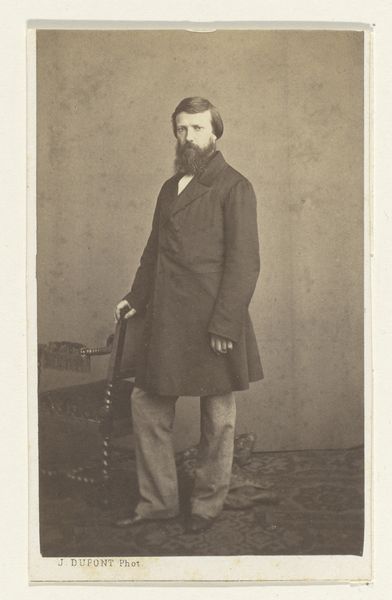

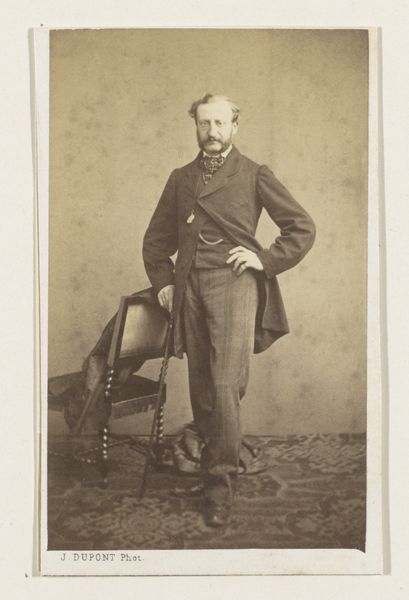

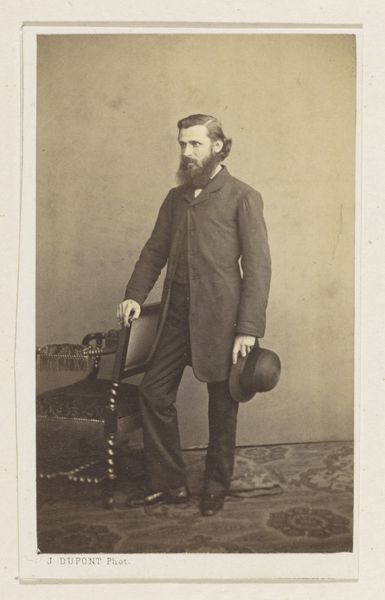

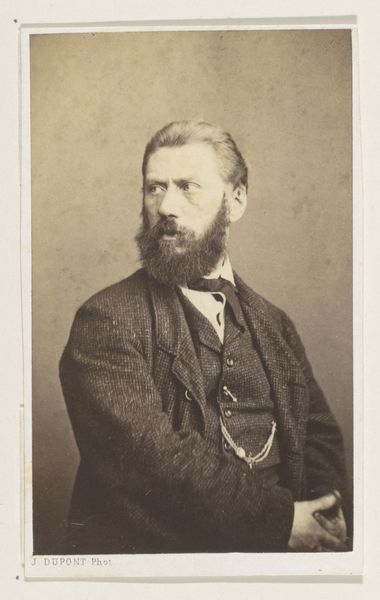

Curator: Let's discuss this dignified image. It’s a gelatin-silver print from 1861 by Joseph Dupont, titled “Portret van de schilder Joseph-Laurens Dijckmans, ten voeten uit”– A full length portrait of the painter Joseph-Laurens Dijckmans. Editor: My first thought is: self-possession. Look at the angle of his arm, his controlled hands. It radiates an aura of someone comfortable with their role in the world. A very self aware Romantic aura. Curator: Indeed. Dupont created this photograph using a then cutting-edge gelatin-silver process. It provided a high level of detail, note the textures in his coat, the rug under his feet and, remarkably, the varnish on the chair. It allows for mass reproduction but carries the aura of Romanticism due to subject and time period. Consider what that meant for artists like Dijckmans, now able to distribute their image so easily, the democratization of persona in the photographic age! Editor: I’m drawn to how that self-assuredness plays into a particular symbol, a carefully curated persona. Notice how he positions himself within the frame? Not directly facing the viewer, but angled slightly, hinting at introspective depths. And then there's the hand gesture...fingers laced but relaxed. It all whispers of calculated intellectualism, the 'tortured' romantic artist in repose. Curator: Precisely, every element – his dress, the ornamented chair, and the Persian rug – contribute to a desired narrative of refined taste. In the making of such photographs, you can truly sense how access and taste had to be crafted by many. Dupont's hand is of course significant in all of that too, isn’t it? Editor: Yes, and observe too, that beard! In the Victorian era, beards were signifiers of wisdom, artistic disposition, and masculinity. It’s as if Dijckmans is using all visual tools available to cultivate his personal brand. It's about cementing one’s image into the collective consciousness through symbolic representation. Curator: Fascinating how this relatively new photographic medium became such a crucial tool for branding and artistic positioning, a mass-produced personal statement, if you will. It allows us to see 19th-century society’s attitude toward labor and class, too. Editor: So true. Studying the portrait reveals more than just a face, but an entire performance built on ingrained symbols of that time. It shows how, even in a supposedly 'objective' medium like photography, representation is deeply woven into our understanding of personhood and cultural expectation. Curator: A productive look at this portrait then – one of materials, reproduction, and intentional craft as well as impactful symbols! Editor: Absolutely. A true synthesis of production and presentation – perfectly encapsulating that moment in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.