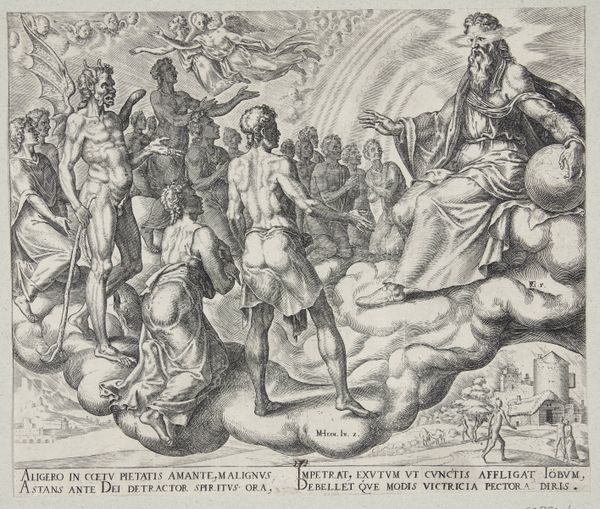

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: 208 mm (height) x 245 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: So, this engraving from 1563 by Philips Galle, titled "Job sitting on the dunghill", definitely throws you into the deep end. It's stark, incredibly detailed for a print, and the atmosphere feels... apocalyptic. What jumps out at you when you look at it? Curator: Apocalyptic is a fantastic way to describe it. To me, it feels like Galle has bottled a nightmare and let it loose on the copper plate. Look at Job there, reduced to almost nothing, yet surrounded by others, each lost in their own form of grief or destruction. The burning city in the background isn’t just set dressing; it’s the psychological landscape of despair made visible. Isn't it interesting how the 'comforters' seem as lost as Job? What do *you* make of them? Editor: They seem more like spectators, or maybe even vultures, circling the carrion of his life. They’re *present*, but not helpful. There’s such a distance between them and Job. Is Galle saying something about the failure of community in the face of suffering? Curator: Precisely! And the Northern Renaissance loved those moralistic messages. Think about it: Galle is taking a biblical story and using it to explore human reactions to extreme adversity. The engraving's sharp lines and almost clinical detail make it less about religious piety and more about dissecting the raw, uncomfortable realities of human suffering and empathy or lack thereof. Makes you think, doesn't it, about who we are when faced with another’s pain? Editor: Absolutely. I came in thinking about it as a purely religious image, but now I see it's tackling something much more universal, something disturbingly relevant even today. It’s uncomfortable but in a way that kind of forces you to examine your own potential failings. Curator: Indeed! And sometimes, that's exactly what art is meant to do. It should invite contemplation on the grand theatre that is life, right? Galle gives us a stark reminder that being present isn’t always enough; we also need the ability to truly connect and, more importantly, offer solace and support. A humbling lesson from an old print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.