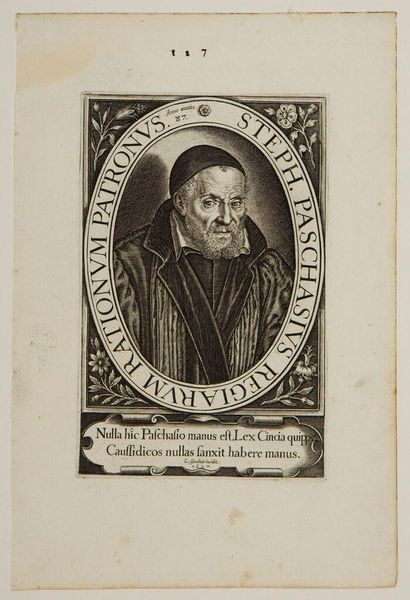

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

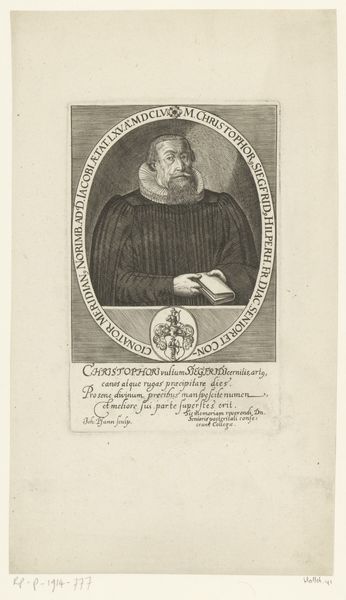

Curator: This is a print from 1613, entitled "Portret van Melchior Sebisch" made by Jacob van der Heyden. It's an engraving. Editor: I'm immediately drawn to the intricate collar. The way it's rendered creates such an amazing play of light and shadow against the darker clothing. The composition really emphasizes a sense of serious formality, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely. This engraving speaks to the rise of printmaking as a vital form of image production in the early 17th century. Think about the economics of this medium— suddenly portraiture is available to a broader segment of society than just the elite who could afford painted portraits. This allowed for distribution of information and status in a way previously unavailable. Editor: The meticulous details achieved with the engraving technique certainly add to that sense of status. Notice how van der Heyden uses line and shadow to sculpt Sebisch's face. The sharp, precise lines defining his features give him such a defined character, especially with those small eyes! And that commanding beard…it all contributes to the portrait's intense presence. Curator: Right. Engravings like this one served very specific social purposes. Beyond mere likeness, they aimed to disseminate ideas about Sebisch himself, maybe enhance his academic reputation, and certainly his professional and social network. The Latin inscriptions surrounding the portrait further solidify this. Editor: The oval frame, too, it really concentrates the focus. This portrait makes it hard to ignore the material and the texture so carefully replicated through line and technique. Van der Heyden is clearly emphasizing Sebisch's imposing nature. Curator: Indeed. So many prints of scholars and professionals circulated in the seventeenth century and these kinds of portrait prints became highly valued as collectibles, often bound into books or kept as records of important individuals, reinforcing class structures, professions, and solidifying their role in a visual culture defined by consumerism and trade. Editor: It gives us such a concise distillation of an era. Thinking about the artist’s intention and the societal conditions of the time definitely enriches the experience of looking at this. Curator: It certainly does give us much to consider.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.