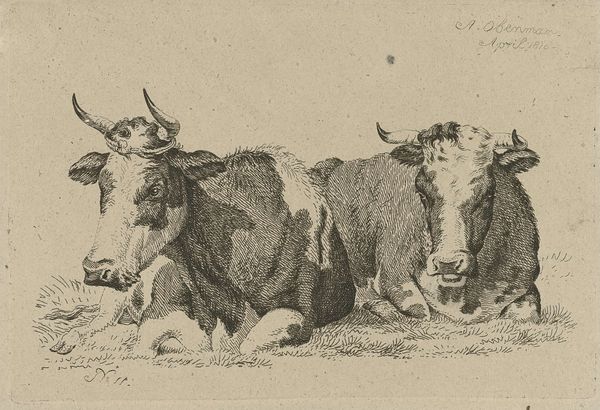

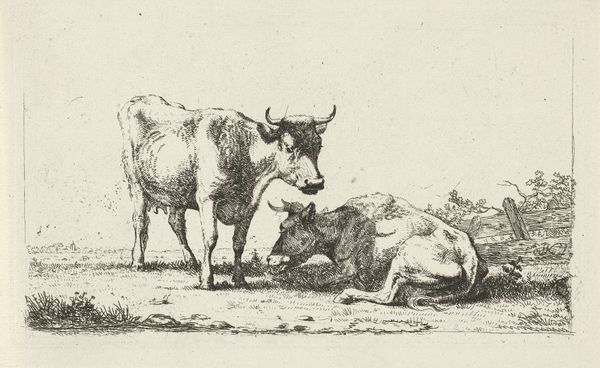

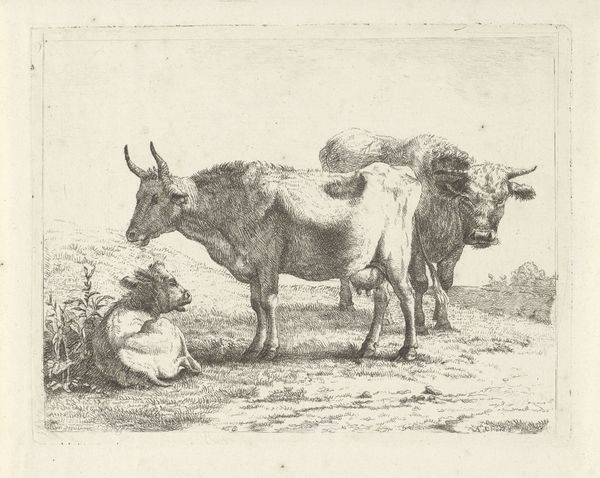

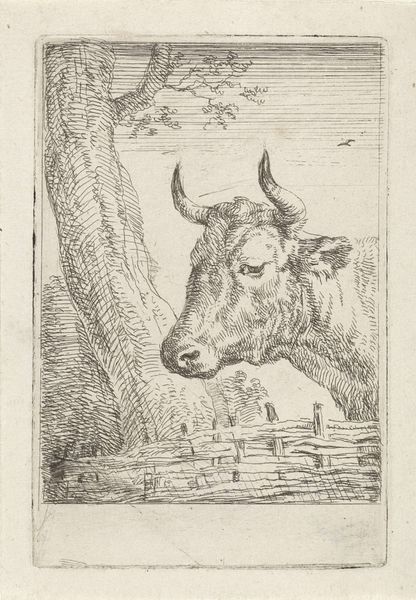

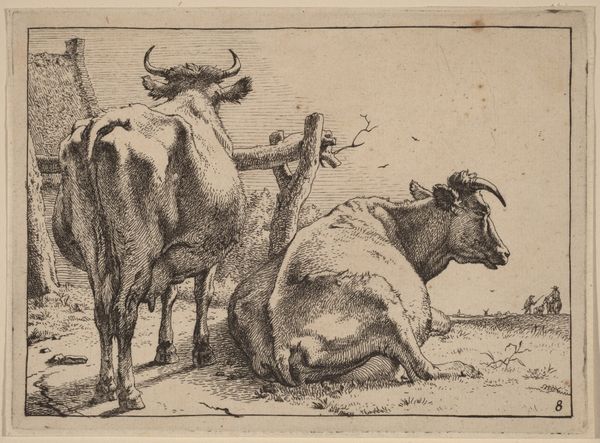

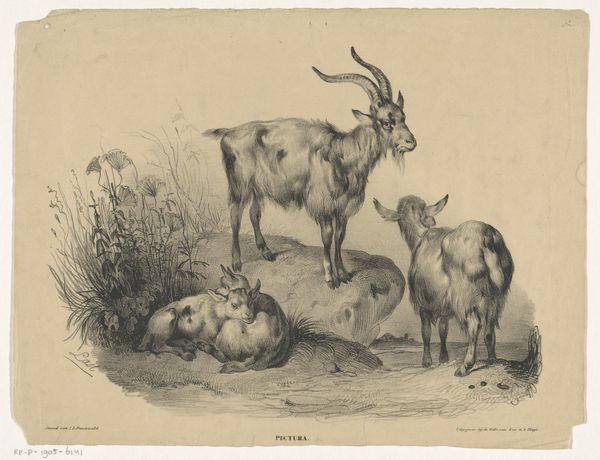

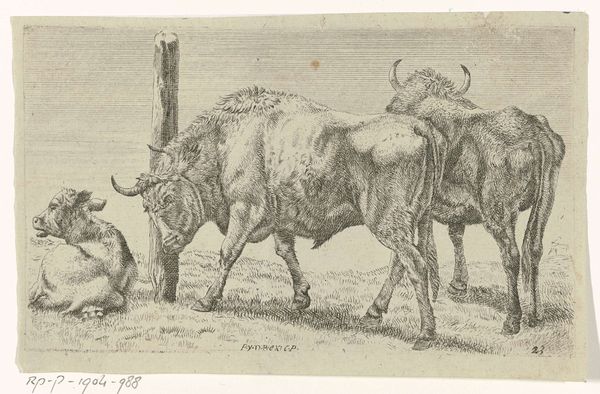

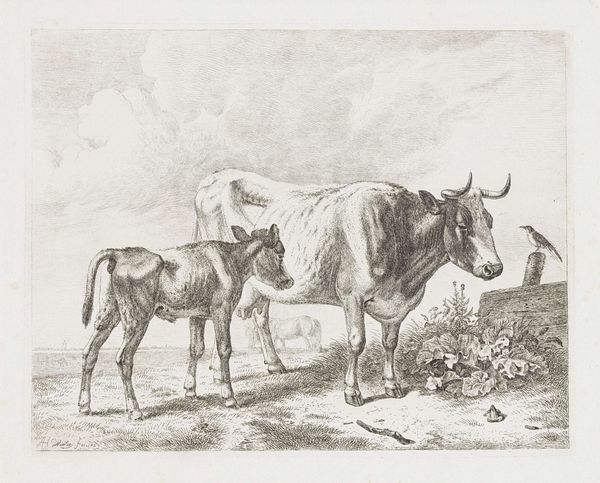

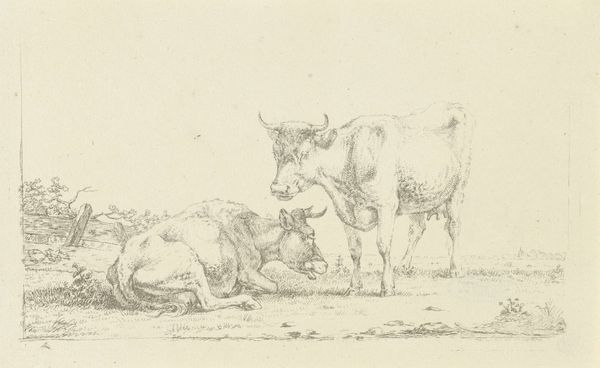

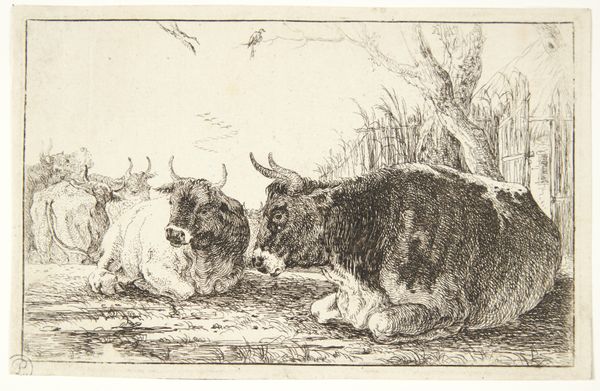

drawing, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Studieblad met paardenhoofd en beestenkoppen," or "Study Sheet with Horse Head and Animal Heads," a drawing made with pen, pencil, and ink by Anthony Oberman in 1809. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, the overall impression is almost clinical. There's a detachment in the rendering, even as the details are carefully observed. It feels like a study in anatomy more than a portrait of individual animals. Curator: Exactly. Oberman's artistic output can be contextualized with his involvement within the Felix Meritis Society, deeply involved in promoting sciences and arts through their drawing academy. Think of this sheet not as mere sketches but part of a wider system encouraging education and skillful workmanship, central to their mercantile ideology. Editor: Interesting. You’re drawing attention to the intersection of artistic production and economic objectives in Dutch society at the time. So, while we see these animal heads—a horse, cows, sheep, goats—are these depictions part of a visual inventory, categorizing livestock as a resource? Does the medium reinforce class boundaries, by any means? Curator: Undoubtedly. Consider the material constraints—pen and ink, pencil—common drawing implements accessible to many who still had some amount of training. The "realism" also adheres to academic-art conventions. So yes, Oberman is likely engaging in both observing the visible and transmitting ideals, so it is possible to regard this as propaganda. Editor: It almost feels like a foreshadowing of scientific illustration. I notice the inclusion of the animal skull; is that simply a formal study on bone structure, or can we read some moral message in its presentation? The skull subtly introduces questions about life, death, and our relationship to animals. It introduces an elegiac note, reflecting the changing agrarian lifestyles, perhaps? Curator: Perhaps both. Its rendering signifies observation, practice and control within artistic apprenticeship while also indicating the role of the animal and our mastery over other forms of labour and lives. These exercises taught the privileged an appreciation and understanding of these systems to facilitate their future positions. Editor: So, while the work on the surface seems a neutral collection of studies, delving deeper reveals its entanglement within social structures. What initially appears as an exercise in academic observation speaks to class, consumption, and perhaps even a premonition about the ecological impact on livestock. Curator: Precisely, it offers a tangible illustration into a mode of both visualizing and categorizing production for the bourgeois public in service of their social and economic aspirations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.