Dimensions: height 81 mm, width 104 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

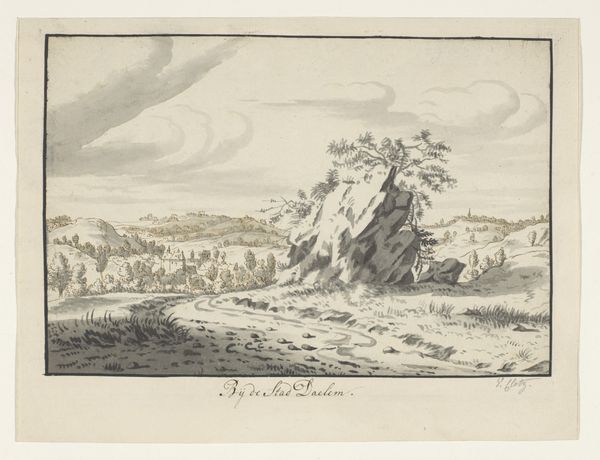

Curator: This is a piece by Hendrik Spilman entitled “Gezicht op Monster, gezien van bij de vliedberg, 1743,” a landscape rendering crafted through engraving and printmaking techniques. The work is estimated to have been completed sometime between 1754 and 1792. Editor: My first thought is one of pastoral tranquility, actually. The soft lines, the billowing cloud, even the tiny figures on the hill—there’s a sense of peaceful observation here. A privilege of perspective, looking down on the village. Curator: That viewpoint is key, literally and figuratively. In the 18th century, the “view” became a popular form, offering patrons and the public controlled glimpses of property, progress, and even idealized versions of society. The elevated vantage implies ownership, control. Editor: Yes, but who controlled that view? Was it accessible to all, or was it a symbol of the landed gentry literally looking down on the common folk, Monster the name of a monster, but also the anglicised word, monster for the common man, so was it looking down on the people? I’m interested in what this imagery meant to the people *in* the landscape. Curator: Precisely. That tension is visible, isn't it? The artwork performs a double duty: at once glorifying the land while subtly reinforcing the social hierarchies inherent in land ownership. Consider the clean lines, a kind of Baroque idealization. But, as you suggest, it isn't just about aesthetics; it’s about power relations made manifest through landscape. Editor: Absolutely. And those minute figures on the hill. They seem to be actively observing. Do they also reflect our contemporary concern with who has the authority to view, and to what end? In an age of environmental reckoning, this piece poses complex questions around land use, exploitation, and the historical roots of seeing the natural world as something to be surveyed, owned, even mastered. Curator: Yes, the art serves as a record of its time while simultaneously questioning those established structures, so as historians we can analyse both the overt and the implicit messages encoded into seemingly simple visual form. It invites an investigation beyond pure representation and prompts to reflect on the larger implications surrounding depictions of land and community. Editor: I agree. Even a landscape so seemingly serene is loaded with power and invites crucial examination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.