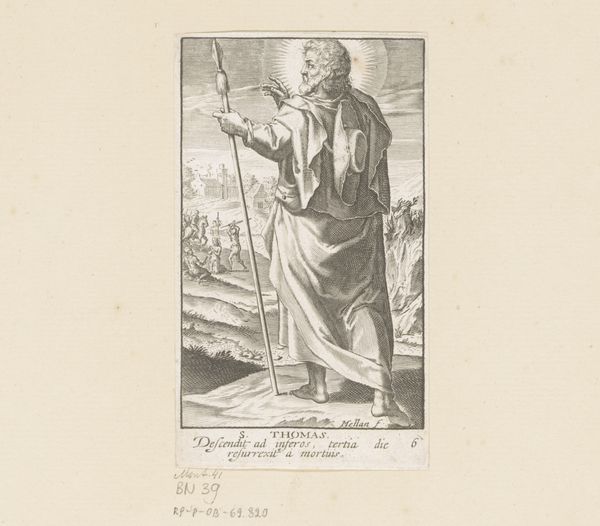

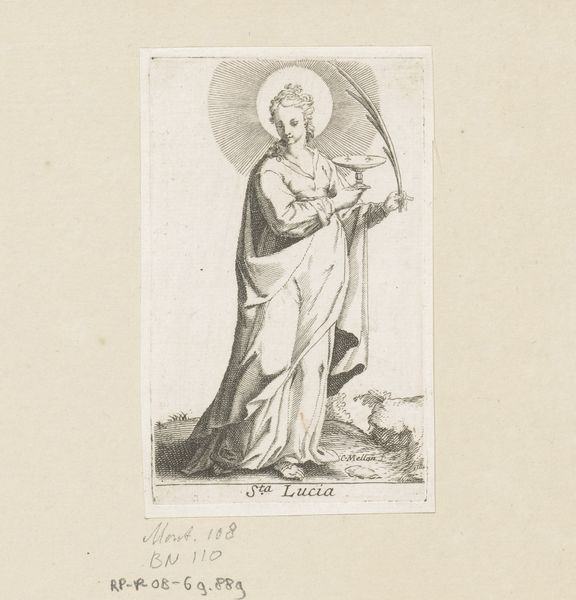

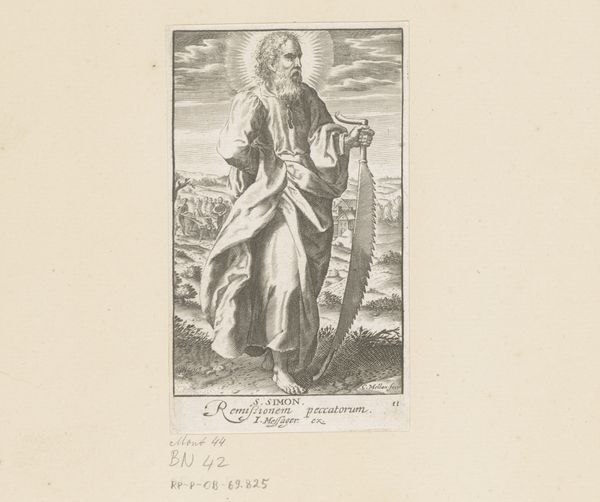

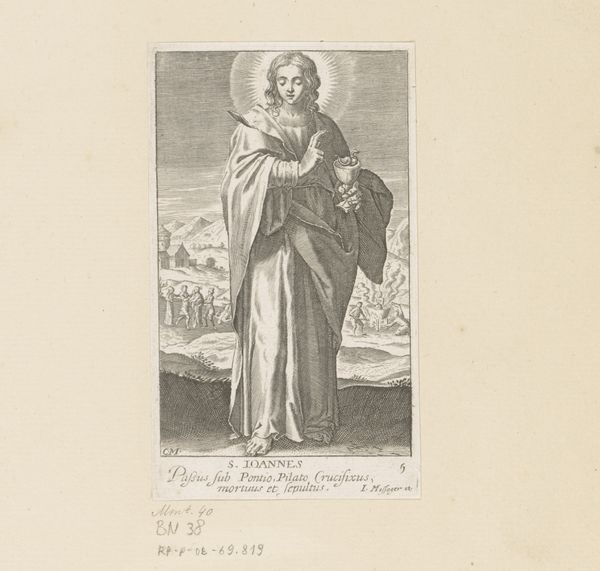

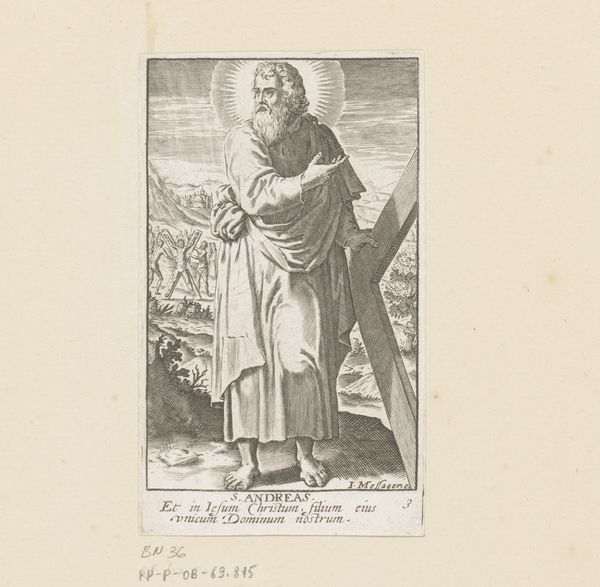

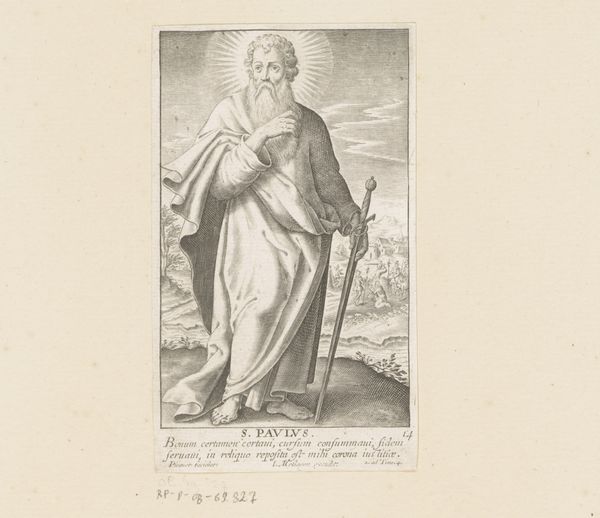

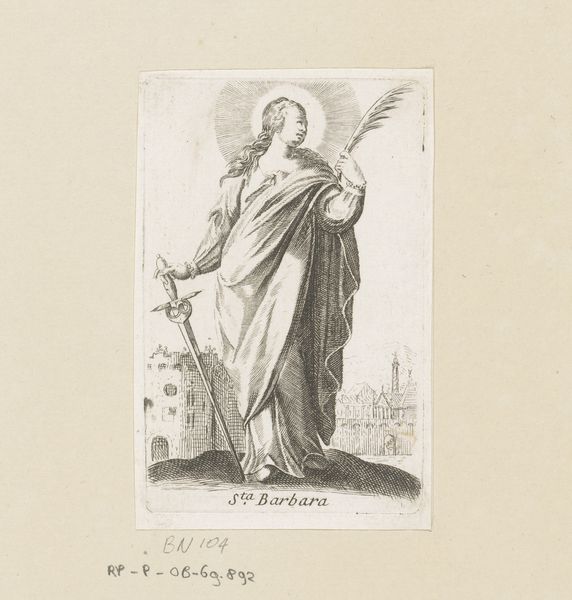

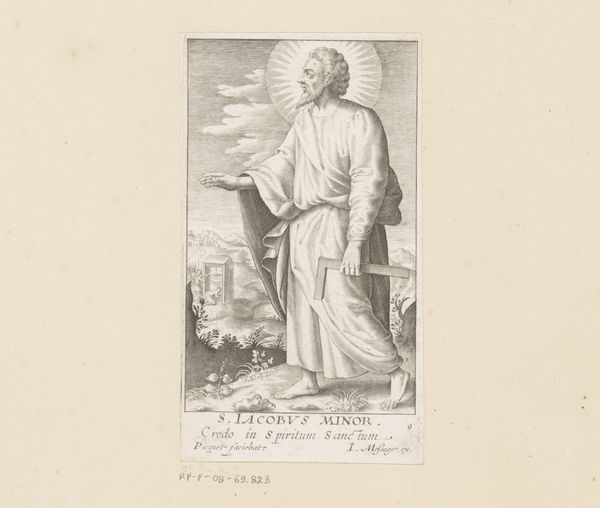

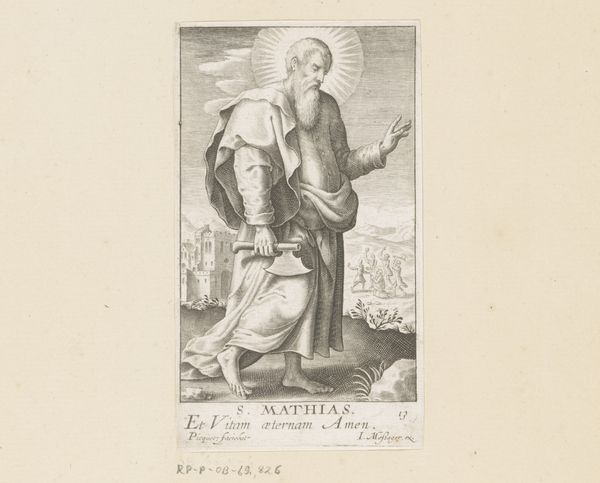

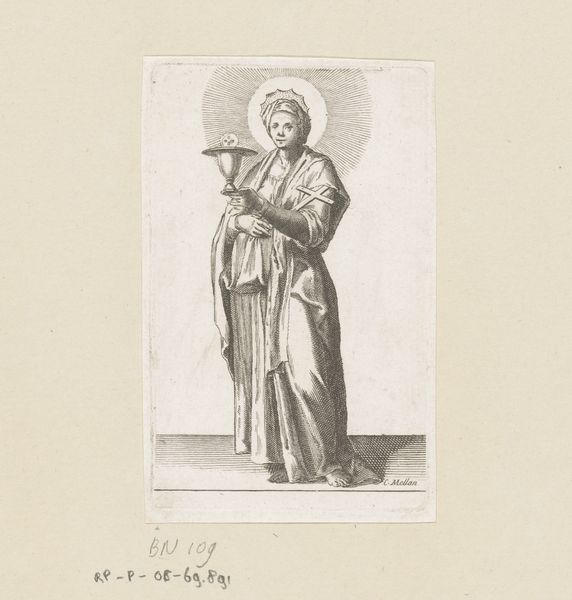

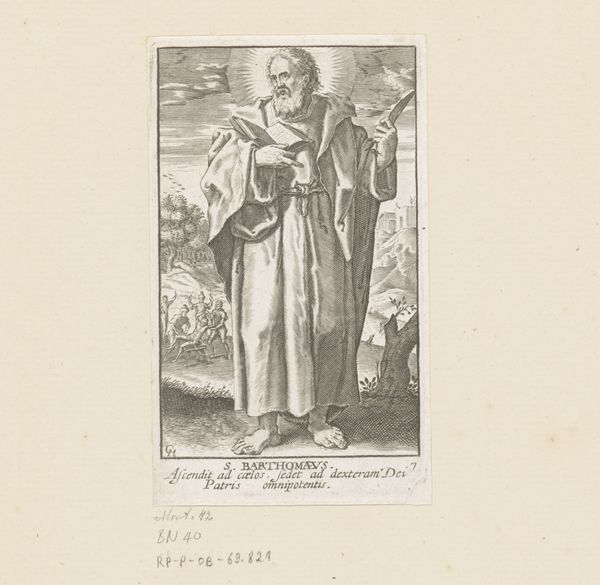

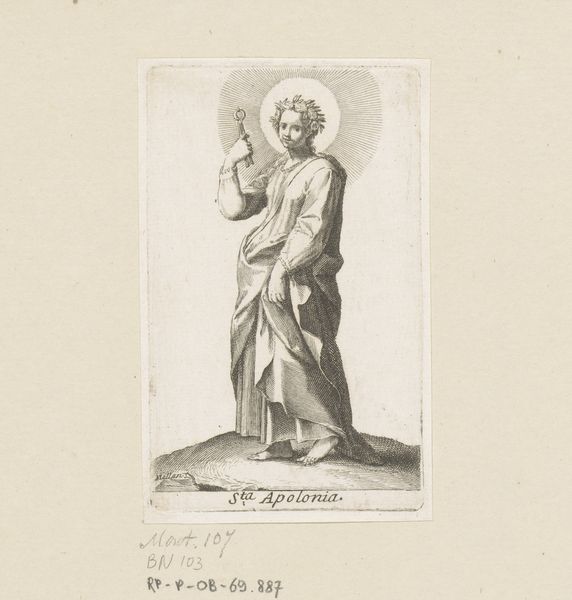

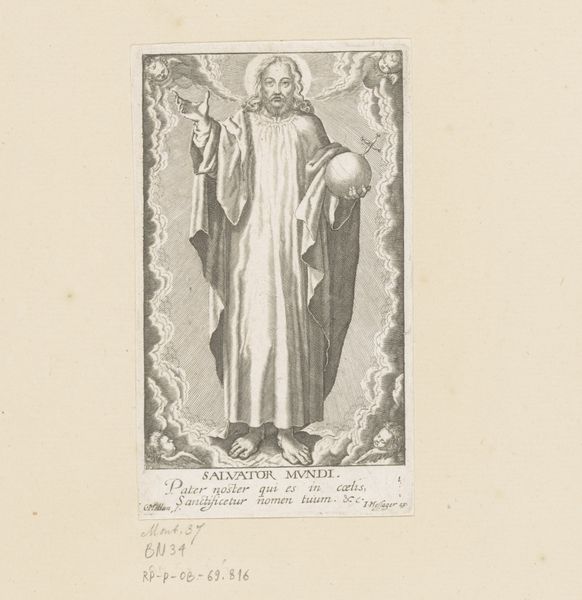

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 68 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Claude Mellan’s "H. Filippus," an engraving dating back to the early to mid-17th century. It's strikingly detailed, almost photographic in its precision, yet the subject matter, a saint with a cross, feels very much of its time. What do you see in this piece beyond its technical skill? Curator: This isn't simply an exercise in technical mastery; it's an assertion of power and faith in a Europe undergoing immense religious and social upheaval. Consider the period – the Counter-Reformation was in full swing. Mellan, through this idealized representation of St. Philip, participates in visually reinforcing the authority of the Church. Notice the cross, his gaze; it’s all carefully constructed to project a sense of unwavering conviction. Editor: So it's more than just a portrait, it's a statement? Curator: Precisely. It's about embodying and propagating a specific ideology. Who gets to be represented, and how, always carries a political charge. Think about the function of images like these in disseminating certain ideas about virtue, piety, and divinely ordained order. Editor: That’s interesting, I never considered how portraits can be part of that dialogue. Curator: Consider the social structures and religious dogmas of the era, the power dynamics embedded within those frameworks, and then ask: what is this image doing within that context? Whose interests does it serve, and what narratives does it reinforce? Editor: Now I am thinking of it more like political messaging, that makes a lot of sense! Curator: Art always participates in broader social conversations. Recognizing those conversations helps us interpret not just what's on the surface, but what's operating beneath.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.