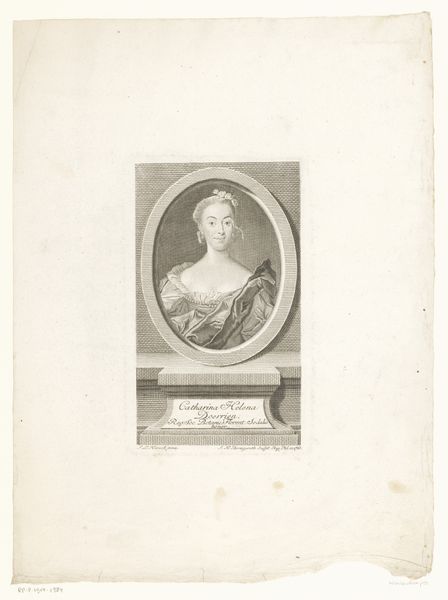

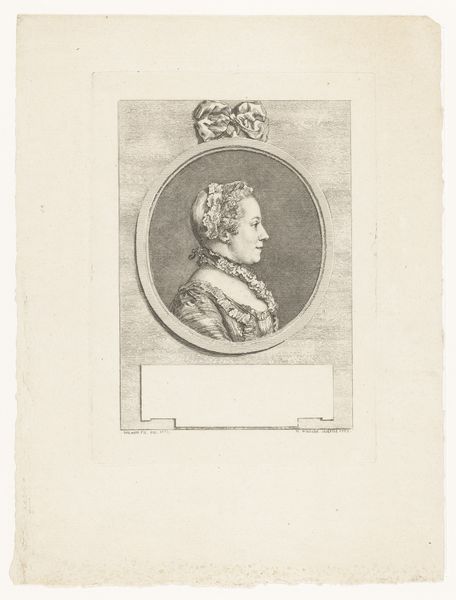

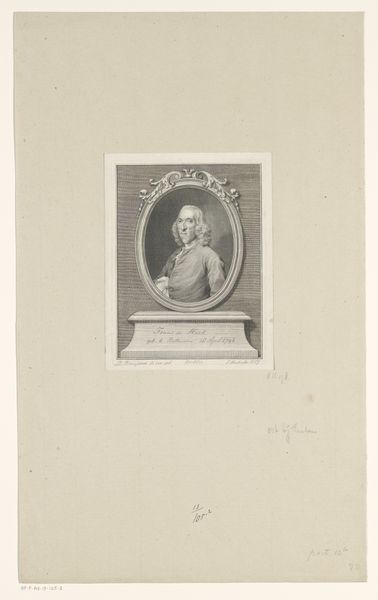

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

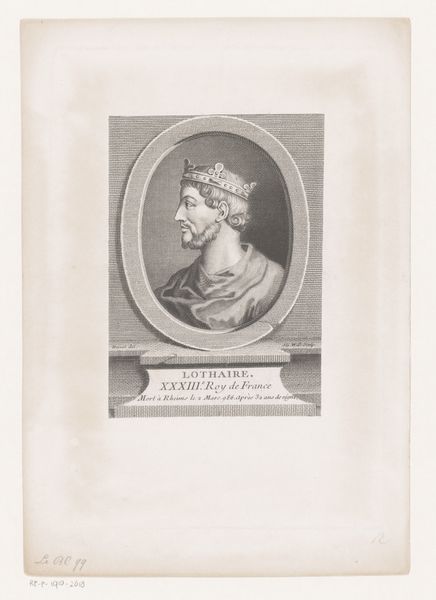

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 231 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving, what immediately strikes me is its sense of contained power, despite its small size. The subject, Wilhelmina van Pruisen, is framed within an oval, almost as if presented as a classical cameo. Editor: It does have that timeless quality. Tell me more about the context; I am curious why such a print was made and its potential reach within the public. Curator: The print, dating roughly from 1767 to 1849 and residing here at the Rijksmuseum, offers us a glimpse into the image-making machinery surrounding powerful figures. The style aligns with Neoclassicism, lending her an air of virtue and stoicism highly valued at the time. It is so austere. Editor: Yes, but look at the text right below the image—clearly meant for wider circulation! And the detail, Iconographer, isn't just about aesthetic. Do you think that oval serves as a distancing device, like she’s always beyond the common gaze? Or that the framing almost mythologizes her as a person? Curator: It absolutely contributes to the myth. By confining her to a perfectly composed space, a very controlled space. Consider the headwear—likely quite fashionable, yet also evoking laurel wreaths of Roman emperors. She becomes less a person and more a symbol of her station, even in these tiny engravings. It subtly says, "Remember your place.” And, by the way, those engravings made that image and her message much more widespread than painted portraiture ever could have been. Editor: And to the common person purchasing the print it became much more approachable than having your portrait painted. So do we agree that Neoclassicism created accessibility, maybe unintentionally, to art? Curator: Exactly. Prints such as these remind us that images have always played a role in shaping perceptions of power. Wilhelmina is consciously constructed here through symbolism of a classical taste. It’s propaganda as art. Editor: So as we conclude our discussion on Wilhelmina Van Pruissen and this print form, would we say this is not only a portrait, but almost a type of proto-meme, designed for the consumption of the elite and not-so-elite, of the eighteenth and nineteenth century? Curator: Yes, I think this highlights the enduring tension of representing power—it’s not just about capturing likeness but carefully calibrating meaning. It echoes through history. Editor: Quite a thought to sit with. Thank you for sharing these illuminating layers embedded in this piece!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.