Dimensions: height 225 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

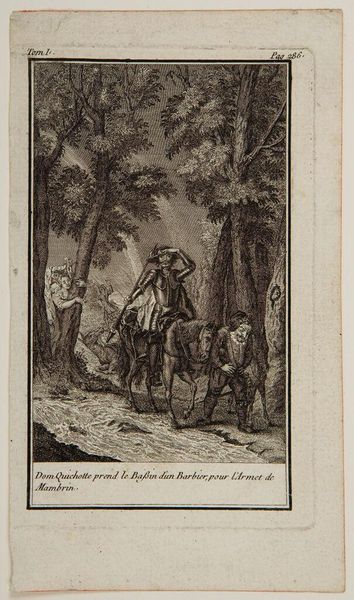

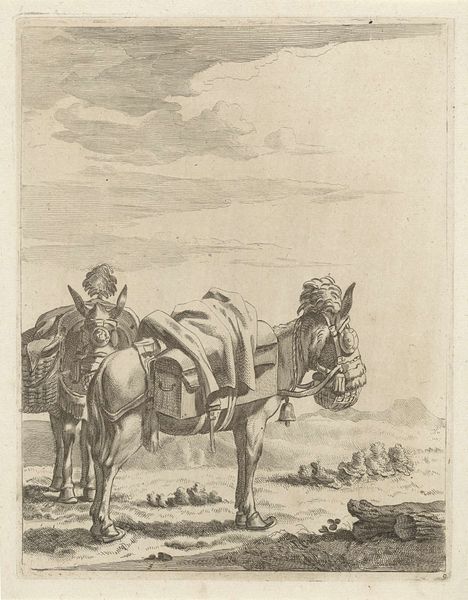

Curator: This engraving, created by Reinier Vinkeles in 1772, is titled "Ruiter en een man bij een bewusteloze jonge vrouw," which translates to "Horseman and a Man by an Unconscious Young Woman." Editor: It’s quite dramatic! The stark contrasts and swirling lines give a real sense of urgency, almost like a stage setting for a tragic play. I’m immediately drawn to the vulnerable figure of the woman on the ground. Curator: Vinkeles was a master of line engraving, and you can see it here in the way he builds form and texture. It’s a print, so think about the labor involved: the cutting of the metal plate, the inking, the pressing… each impression is a product of skilled craft. What might it have cost someone in the 18th century to acquire such an image? How would it have been circulated, consumed? Editor: Good points! The social context is key here. What does this scene tell us about societal expectations and power dynamics of that time? A young woman, seemingly vulnerable, a man rushing to help, and another observing from horseback— it speaks volumes about gender roles and perhaps class distinctions, the figure on horseback looks richer than the other male character who seems like her rescuer. I wonder about Amalia, named in the text on the artwork itself: could she be linked to broader narratives of victimhood in art? Curator: Certainly, these narrative prints often served to moralize or depict scenes from popular literature. But also consider the technical expertise involved in achieving such delicate lines. Think about the engraver's workshop: the apprenticeship, the tools, the collaborative process if any. It gives new weight to what we perceive as "high art." It shows an intricate industry, a precise form of material making with complex socio-economical ramifications behind the scenes. Editor: Yes, situating it within those social frameworks really adds depth. The woman's posture is evocative; and there’s also the question of authorship and agency. Does this depiction reinforce certain stereotypes? What possibilities does art offer us to challenge assumptions linked to victim blaming narratives even back then? What is our responsability when looking at similar portrayals of unequal power dynamics nowadays? Curator: Thinking about the labor, the reproduction, helps ground the discussion in something more tangible. It avoids seeing the print merely as a static illustration detached from lived realities. Editor: Ultimately, it’s about unpacking those layers, and recognizing that the image is as much about the social fabric it emerges from, as it is about the figures depicted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.