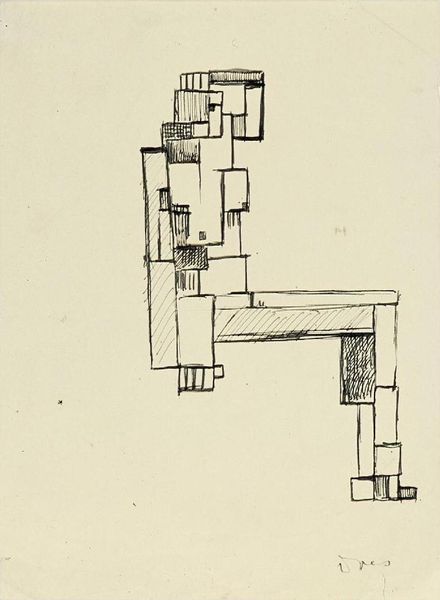

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

de-stijl

#

paper

#

form

#

ink

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

line

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 229 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

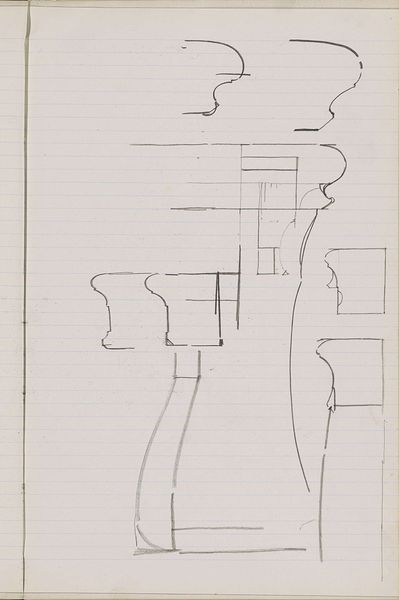

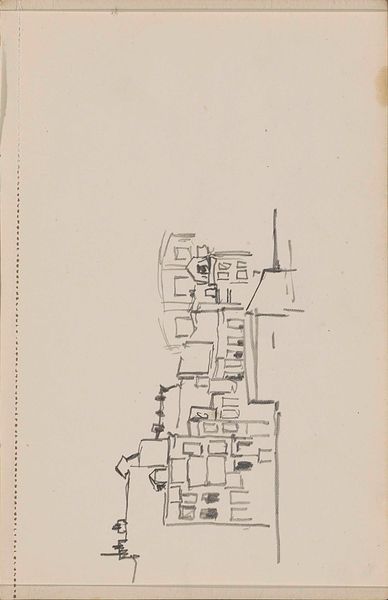

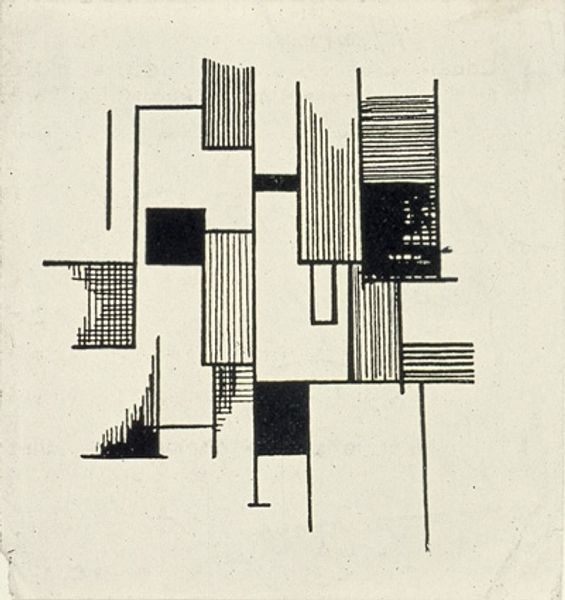

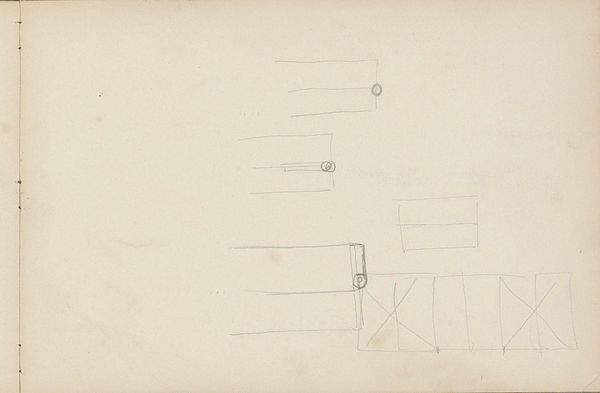

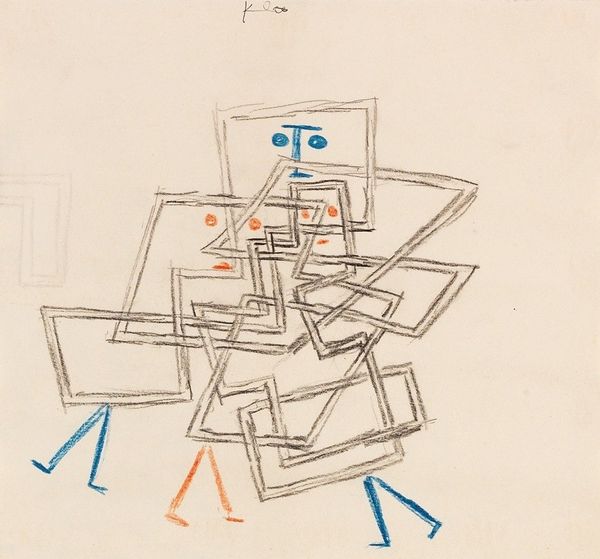

Curator: Okay, let's talk about Theo van Doesburg's "Seated Female Nude, her Hand on her Head," created in 1916. It's an ink drawing on paper, a very distinct piece within his exploration of De Stijl principles. Editor: Wow, well... it's definitely... something. I see this figure constructed from rectangles and squares like she's been architecturally drafted, right? Sort of unsettling, almost clinical. It's the most un-nude nude I’ve ever seen. Curator: Indeed, and that's the fascinating tension here! De Stijl was about stripping down to essential forms, universal harmony through pure abstraction, moving past the individual and the subjective, in part through radically simplifying everything into horizontals and verticals. It seems paradoxical to then apply this to the female form, historically so charged with meaning. Editor: So, the societal view on the female figure goes through a filter of radical objectivity. I can see how it might serve as a social critique—questioning conventional representation and maybe even societal objectification. A deliberate reduction of the figure as commodity. Curator: Precisely, but let's remember Van Doesburg’s own internal motivations, too. World War One impacted everyone, including him. There's an angst, a discomfort. Could the choice to disassemble the female form also reflect a destabilizing world? And, what I think is often missed, a surprising wit in using stark geometry for a topic known for sensual curves. Editor: Wit? Really? I mostly saw tension—almost like a beautiful body has been redacted or censored by the horrors of war! Perhaps it shows his sense of humor or lack thereof... Maybe black comedy was en vogue then? It definitely seems stark for its time. Curator: Well, I see both tension *and* a dry cleverness. His abstraction feels deliberate in pushing boundaries but he is also exploring universal ideals during extreme conditions. This creates a new role for the nude – not mere object, but thought-provoking social sculpture. The reduction is not just aesthetic but purposeful. Editor: A rebellious form. I appreciate learning that now. It challenges our preconceptions on multiple fronts—formally and socially. Okay, it makes the whole piece even bolder. Curator: Precisely! Thank you.

Comments

rijksmuseum about 2 years ago

⋮

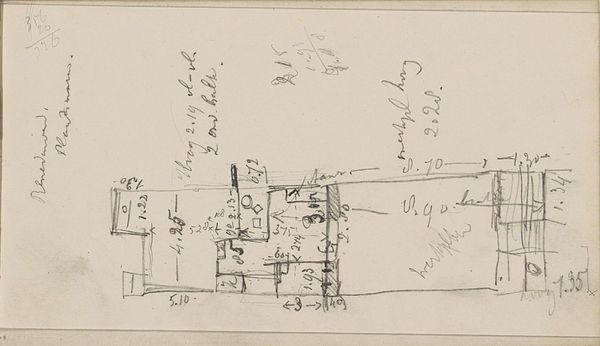

Van Doesburg described in a letter that he had attempted ‘to introduce rhythmical movement in the torso and create a flat sense of space through lines and planes’ in this work. The drawing was the result of ‘further abstraction,’ by which he meant reducing the subject-matter to elementary forms. As for his colleague Mondrian, for Van Doesburg this was the path to a new, universal art.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.