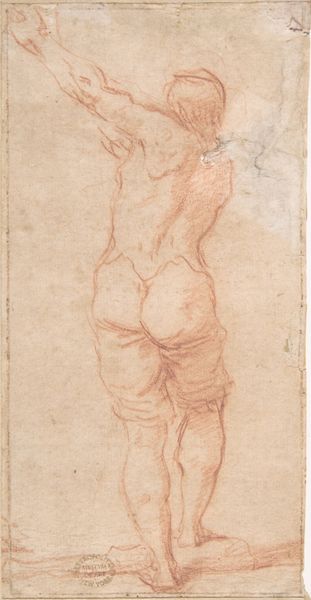

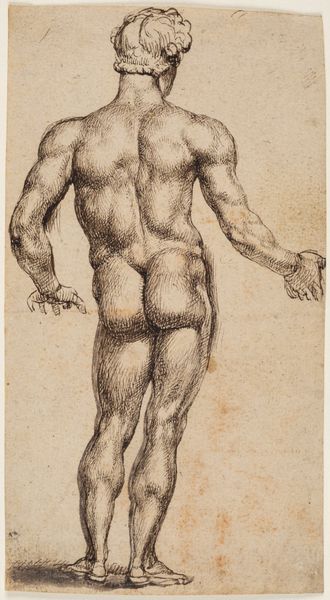

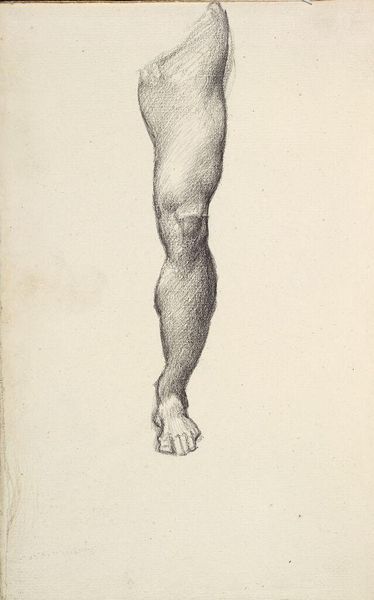

Copy of a Statue with A Female Nude From Back 1550

0:00

0:00

bartolomeopasserotti

Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

pen

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: 26.4 x 8.8 cm

Copyright: Public domain

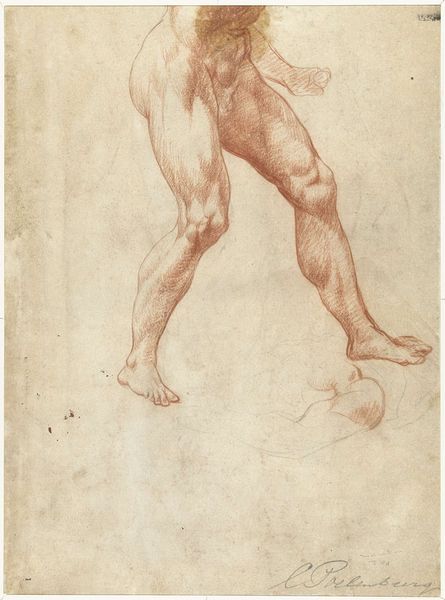

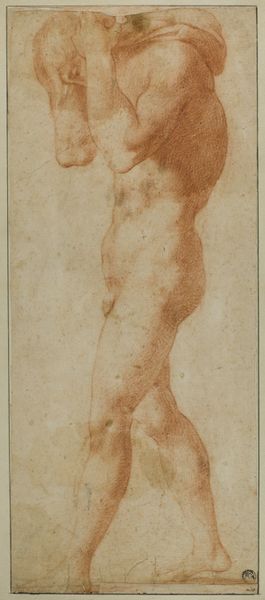

Editor: So, here we have "Copy of a Statue with A Female Nude From Back," a pen and ink drawing on paper by Bartolomeo Passerotti, dating back to about 1550. What immediately strikes me is the incredible detail in the musculature, especially considering it's a copy. What can you tell me about the cultural significance of copying classical statues at this time? Curator: This piece really highlights the Renaissance fascination with classical antiquity. Artists like Passerotti didn't just passively copy; they actively engaged with these classical forms. They were participating in a broader cultural project of reviving classical ideals within a Christian context. Notice the musculature—what message might a renewed interest in human anatomy, seen through the lens of idealized classical sculpture, convey about shifting societal values at this time? Editor: It feels like a shift from spiritual to more humanistic concerns? That the body is celebrated? Curator: Precisely. And that celebration, or renewed focus, also speaks to the power dynamics within artistic institutions. Consider who commissioned these works, who had access to classical sculptures, and how this knowledge solidified their social standing and artistic authority. Was this accessibility universal, or limited by factors such as social class, gender, or geography? Editor: I hadn't really considered that. So copying wasn't just about skill, it was also about participating in a very exclusive and powerful discourse. Did that influence whose work was preserved? Curator: Absolutely. The art that survives, the artists we know, and the stories we tell are all filtered through layers of social and political influence. It’s not simply about individual talent, but about the historical forces that shape what gets remembered and valued. What do you make of the damages or smudges to the original artwork; does it change your view of the artist's intent or society’s values then versus now? Editor: This makes me think about what institutions, like the Prado, choose to display and how those choices influence what we consider "important" art today. Curator: Exactly! And thinking critically about those choices is key to understanding the broader politics of imagery and art history itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.