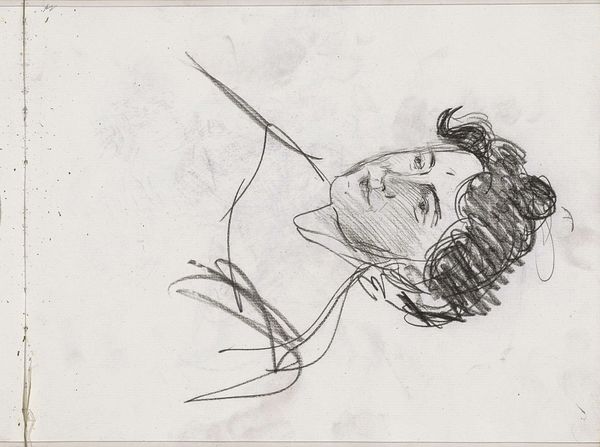

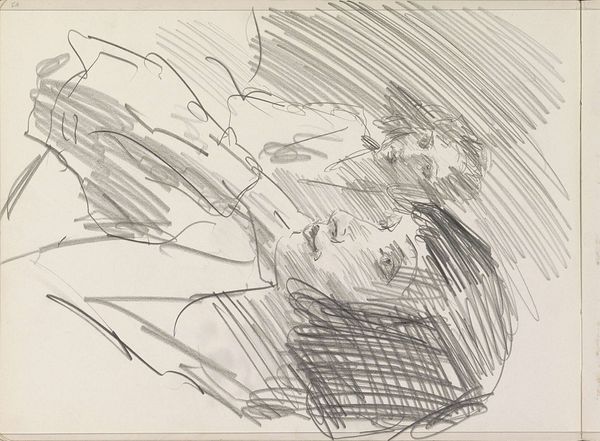

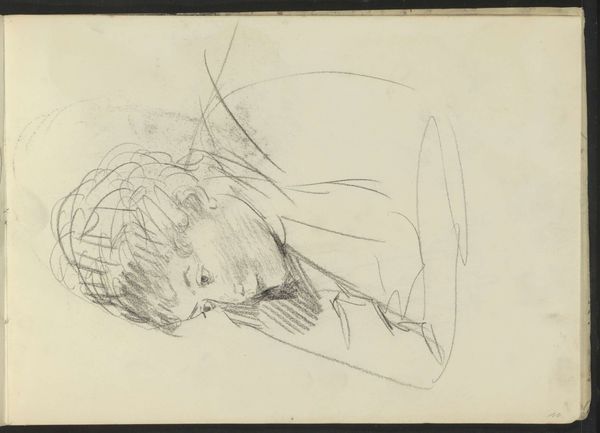

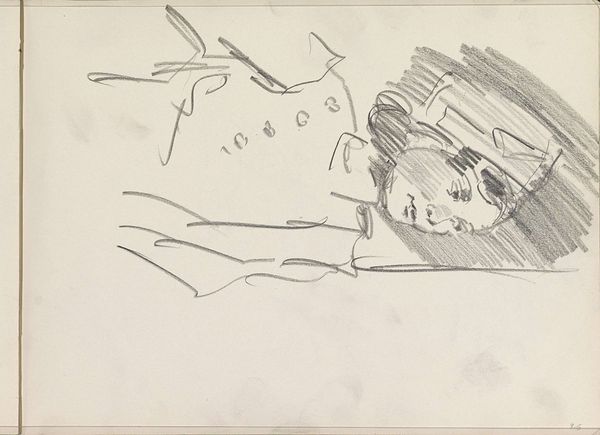

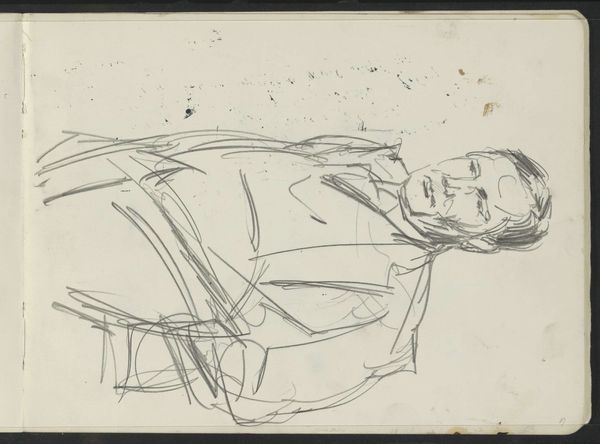

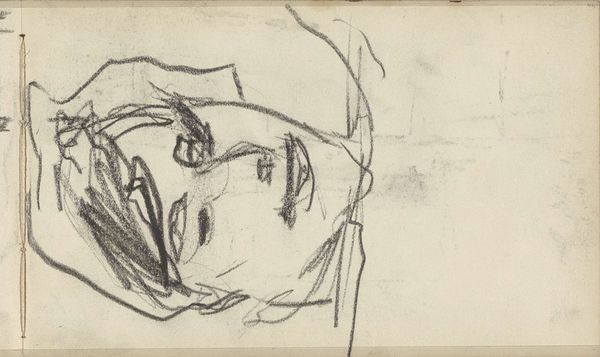

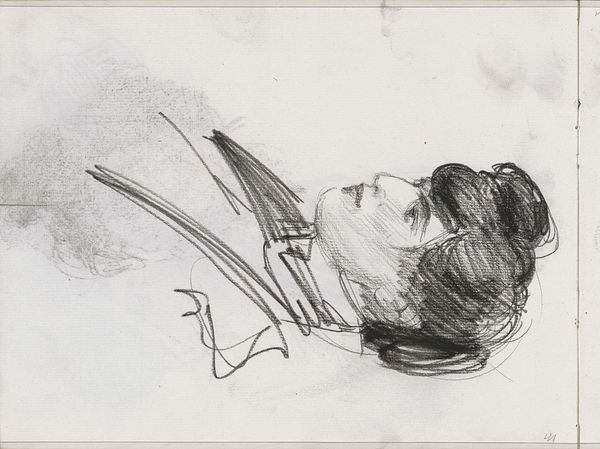

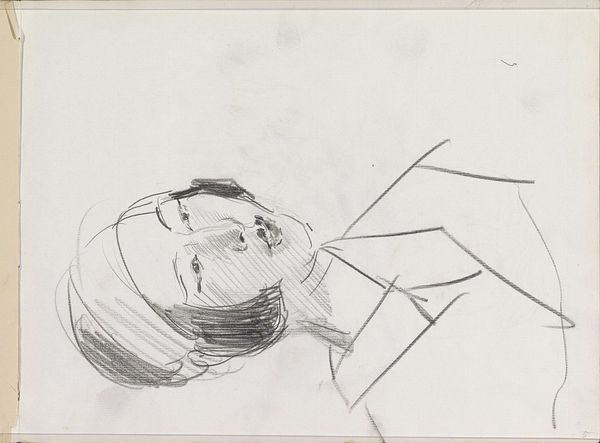

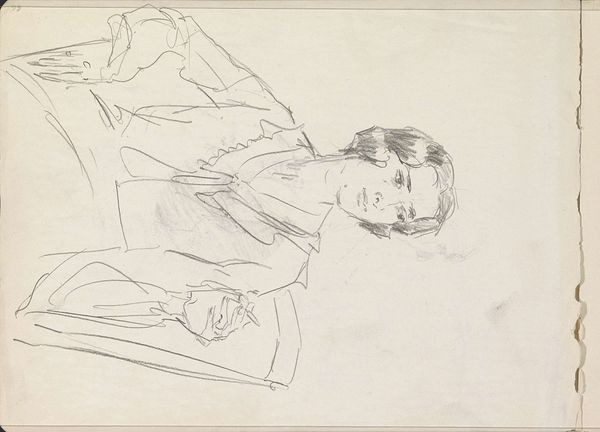

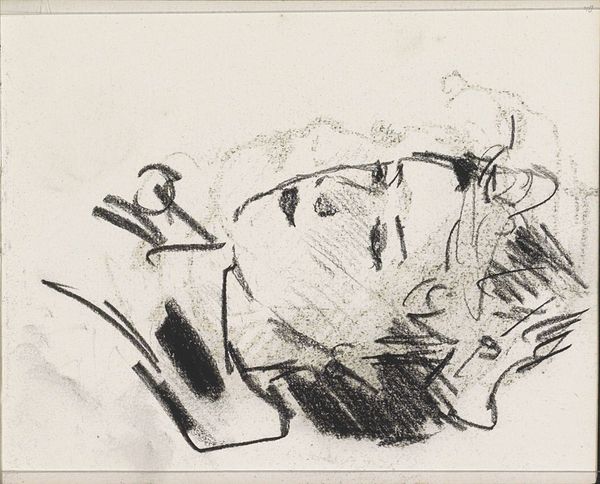

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

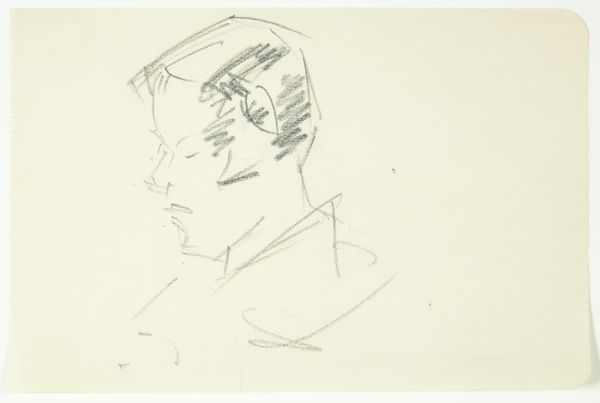

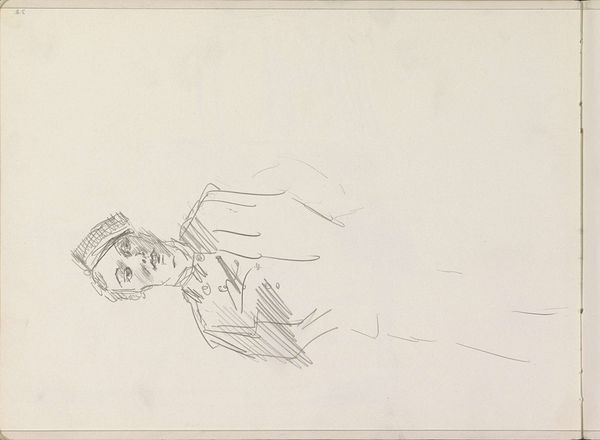

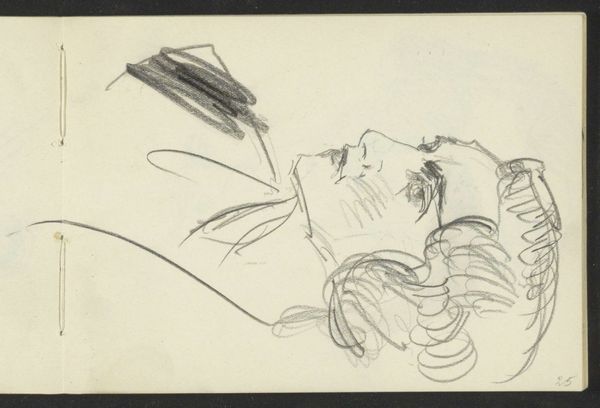

Curator: Here we have Isaac Israels’ “Portrait of an Unknown Woman,” created sometime between 1875 and 1934. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum, a delightful little drawing done in pencil. Editor: Delightful is a good word. I see a ghost of a person emerging from the frenetic lines, like she's trying to materialize from thin air. There’s a fragility there, a sense of fleeting presence. Curator: Yes, the energy is raw, almost like a snapshot of a thought. You know, Israels had this way of capturing modern life, and this feels like a study for a larger work, perhaps, a glimpse into the artist’s process. The immediacy of it makes me feel like I am in the presence of an artist in his most intimate of creative experiences. Editor: The unknown woman, she represents a cipher, a blank page onto which we can project so many identities. Was she one of the many women navigating burgeoning cityscapes at the turn of the century? What agency, what power did she possess? I mean, how can we possibly talk about the “modern” experience without putting questions around women's role into our consideration? Curator: A sketchbook piece. You almost wonder if she was even aware she was being drawn! Perhaps this anonymity protects her story somehow, and maybe gives us more room to ponder the universal experiences she had rather than digging to uncover any personal biography. I find myself in a contemplative mood; do you find her vulnerable in some ways, too? Editor: Vulnerability is there, undeniably. I notice how her features are only loosely defined; almost anyone could be imagined into the place where her real face ought to be. So maybe the piece then, with its seeming disposability and “unimportance,” grants her a temporary shield from our assumptions based on physical appearance alone. It's a delicate balance of exposure and protection in this sketch, as if we are intruding upon an intensely private thought. Curator: Absolutely, a moment captured before it solidifies into something concrete. That, I think, is the heart of impressionism – a feeling rendered in light and shadow. A passing whisper turned into a lasting observation. Editor: I agree; even as we talk about history, we keep bumping into our own biases and present-day narratives. The image seems to allow for continuous revisions in interpretation. Maybe the role of a sketchbook sketch is that it exists not in a final state but lives in between possibility and certainty? Curator: Well said! That liminal space, where intention meets chance, is what makes Israels' work, even this simple sketch, so endlessly captivating, right? Editor: Precisely. Here's to those in-between spaces—art and life alike!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.