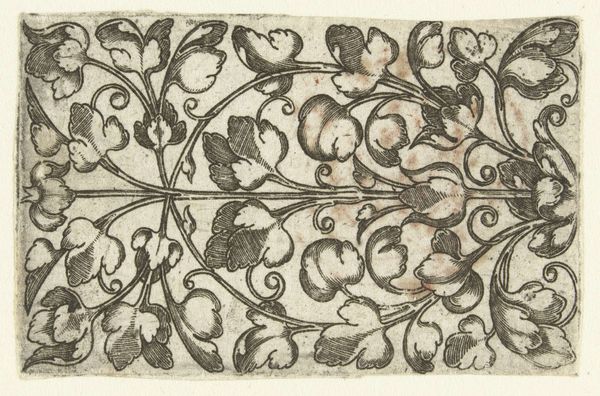

print, engraving

#

naturalistic pattern

#

organic

# print

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

organic pattern

#

intricate pattern

#

line

#

pen work

#

northern-renaissance

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

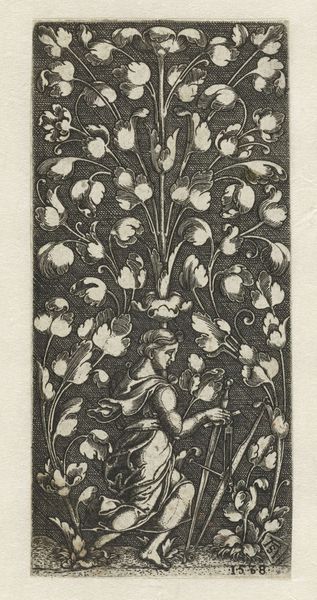

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 35 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, called "Vlakdecoratie met bladranken," which translates to Plane Decoration with Leaf Tendrils, dates back to 1534 and is housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Its creator remains unknown. Editor: Wow, it's incredibly detailed. A dense, almost overwhelming pattern, meticulously rendered. The organic forms – the leaves and tendrils – create a very visually active surface. Curator: It's an engraving, which explains the precise linework. These types of decorative prints were quite popular in the Northern Renaissance. They served as models for artisans – goldsmiths, tapestry weavers – needing design inspiration. Imagine, this small print influencing the grandest decorative projects. Editor: Exactly, I was just thinking about the labor involved! The transfer of this design onto another medium—perhaps metalwork, tapestry, whatever it is. It shows that skilled handcraft relies heavily on pattern books to diffuse the designs across workshops. Look closely; this isn't just some floral fantasy. I spot what appear to be stylized cornucopias at the base, figures… and what is that at the top, an owl? Curator: Good eye! The owl is perched on a shallow bird bath. These incorporated motifs, drawn from both nature and classical antiquity, reflect the humanistic interests of the era. Prints like this democratized design, making sophisticated ornamentation available beyond elite circles. The printing press, an agent for change. Editor: Yes! What seems like just another pretty design actually holds socio-historical traces. The accessibility factor definitely shifts how we consider “high art.” But technique here matters too, as it's all about lines, hatching, the conscious distribution of light and dark areas for maximum impact. You can nearly feel the pressure of the burin carving into the copper plate. Curator: And let’s remember the original context. This print wasn't conceived as something to be framed and displayed like a painting. Its function was practical, to be used, re-used, and quite likely, discarded once its design had been appropriated. So our perception of it today, preserved in a museum, is fundamentally different from its original intent. Editor: True. Its survival elevates the print from mere template to object of study, sparking curiosity about craft and production that’s deeply interconnected with history. Curator: Seeing it this way brings us back to recognizing art as deeply connected to its moment of creation, not isolated from the real world. Editor: Definitely; now when I look at it, I feel invited to delve into 16th-century workshop practices instead of just a pretty surface design.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.