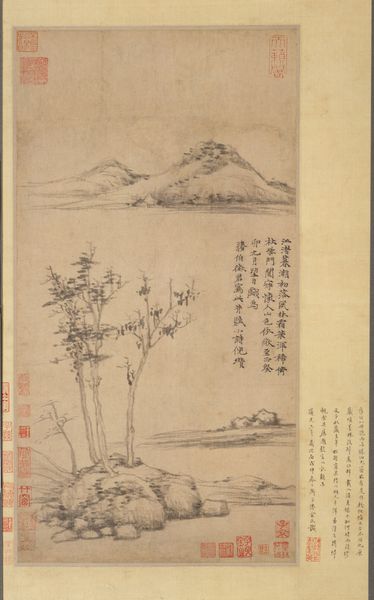

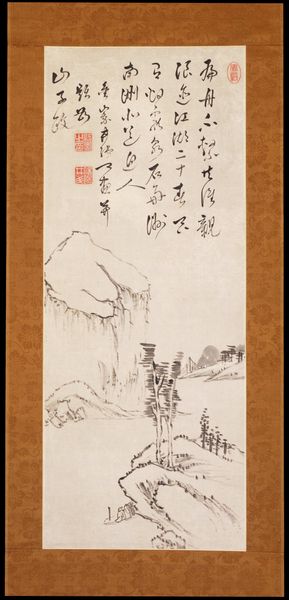

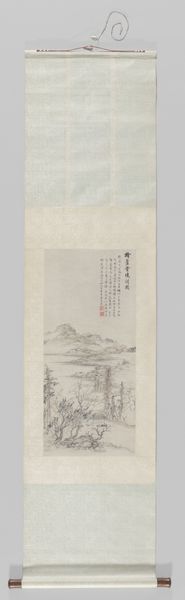

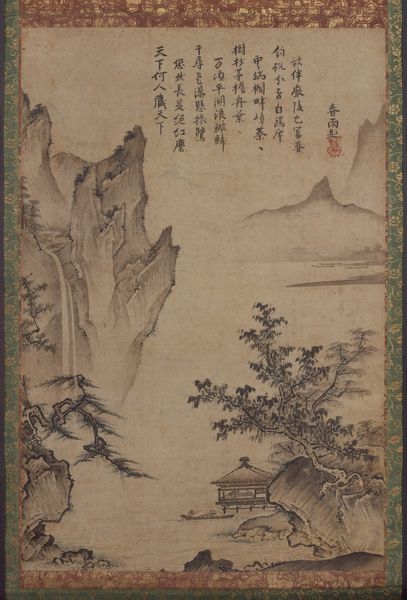

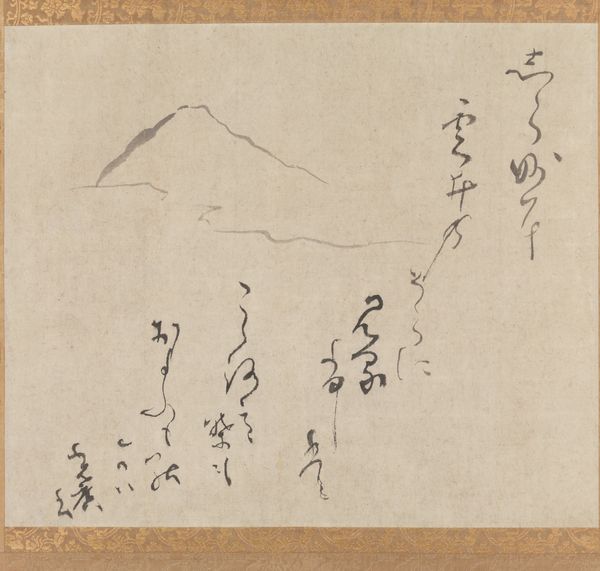

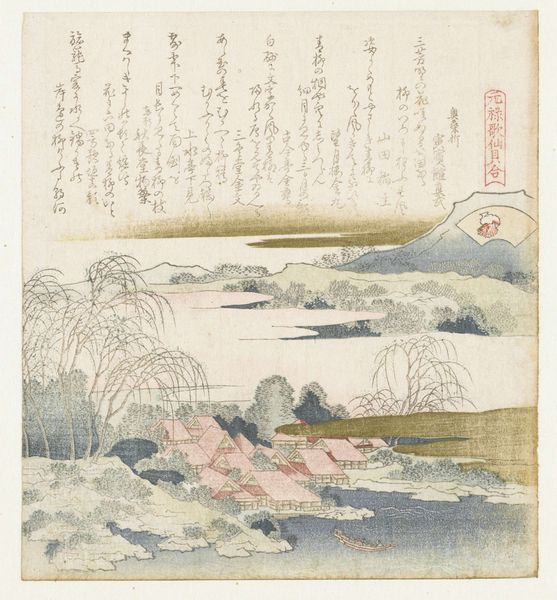

drawing, paper, watercolor, hanging-scroll, ink

#

drawing

#

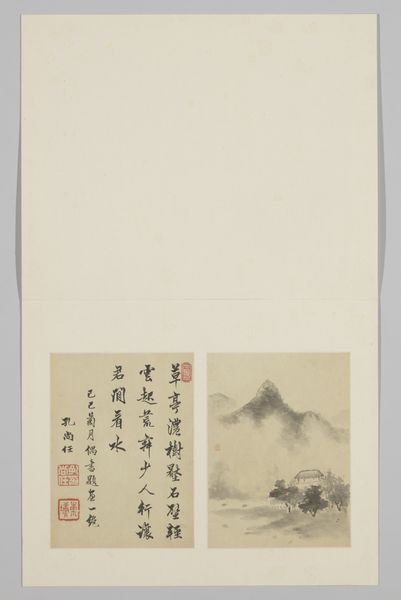

water colours

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

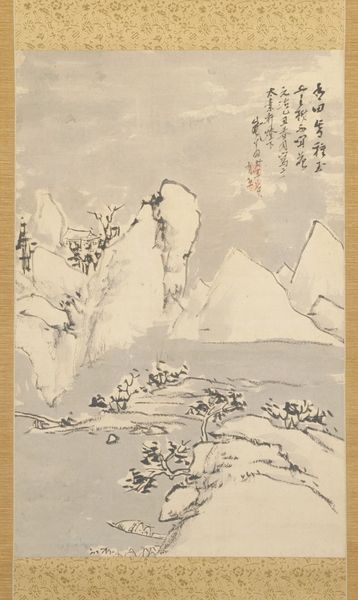

Dimensions: 30 7/8 × 11 3/8 in. (78.4 × 28.9 cm) (image, without text)74 1/4 × 17 1/4 in. (188.6 × 43.8 cm) (overall, without roller)48 1/8 × 11 in. (122.2 × 27.9 cm) (image)76 1/2 × 20 1/2 in. (194.3 × 52.1 cm) (mount, with roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

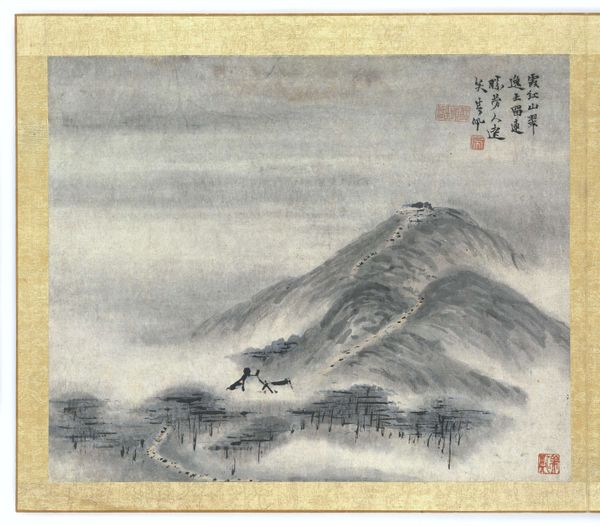

Curator: Here we have Wang Jianzhang’s "Ode to the Pipa," a hanging scroll from 1650, done in ink and watercolor on paper. I see it’s making its home here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art these days. Editor: It strikes me as remarkably serene. All muted blues and greys, like a misty memory of a landscape. The brushstrokes are so delicate; it almost feels like the image could float away. What are your initial thoughts about the piece? Curator: Well, beyond the surface beauty, consider that these landscapes weren't just about pretty scenery. During Wang Jianzhang’s time, landscape painting became a way for literati like himself to express their inner lives and social philosophies, especially amidst political upheaval. The presence of the tiny figures in a boat underscores humanity's smallness relative to the vastness of the natural world, echoing Daoist sentiments. Editor: You’re right, that human element—pun intended— is easily overlooked. Do you think the poem inscribed above is intended to expand the appreciation of the whole artwork? I wonder, is there something intentionally egalitarian in the placement of that poem? Curator: Absolutely, it serves multiple functions. On one hand, it directly references the pipa, a Chinese lute, perhaps hinting at the pleasures of music and companionship found in nature. On a socio-political level, literati artists used these visual and literary components to project their virtues, intellectualism, and cultural refinement, aligning them with esteemed scholarly traditions. That explains why the seals or stamps occupy nearly the entire artwork as well. Editor: Thinking of viewers centuries on, that sense of personal, artistic and scholarly legacy—the weight of cultural continuity, perhaps—becomes palpable. This hanging scroll presents a space to ponder not only nature but our place within it. Curator: Indeed. Wang Jianzhang gives us a reflective surface, so to speak. It's more than just what he painted, but rather how that painterliness provides pathways into historical moments.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The artist Wang Jianzhang’s inscription tells us that he painted this work for his friend Gong Weiliu in 1650, after Gong acquired Wen Jia’s calligraphic rendering of the “Pipa Xing” (“Song of the Pipa Player”), a famous poem. Both Wen’s script and Wang’s painting were mounted together on the same scroll. This famous Tang poem, composed by the poet Bai Juyi (772–846), is one of the great poems of Chinese literature. In it, a man encounters a woman playing a stringed instrument called a pipa and expresses the sadness he feels when he hears her play her melancholy song. Here, Wang depicts the woman standing on a boat in the moonlit river, playing her instrument. Interestingly, she faces away from the viewer, hiding her expression; her sorrow, as well as her beauty, is obscured.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.