daguerreotype, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

#

realism

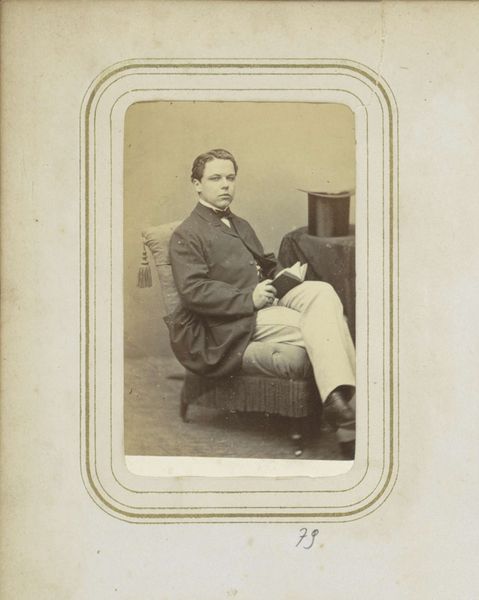

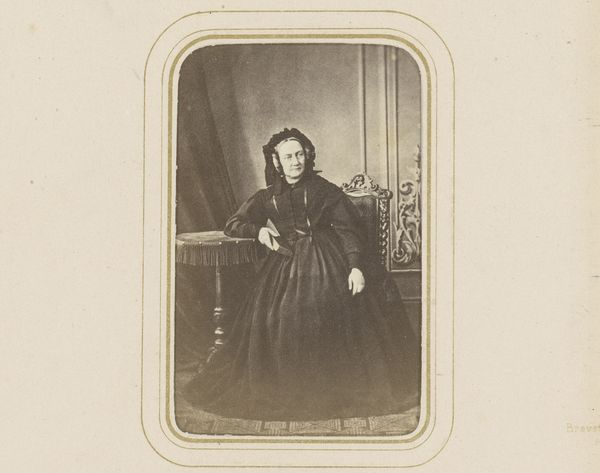

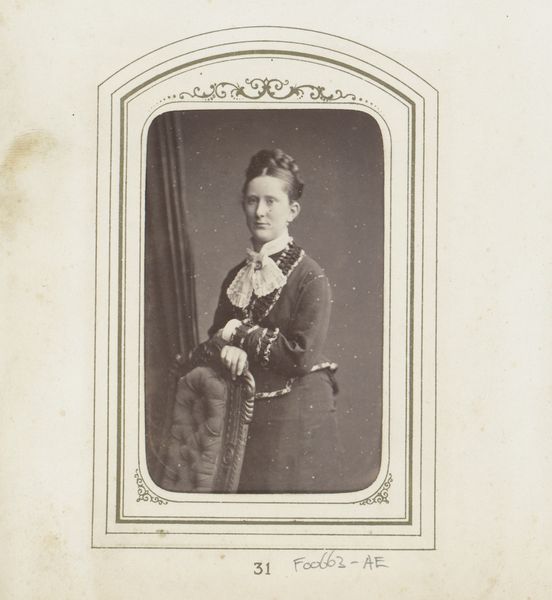

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 53 mm, height 97 mm, width 59 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This albumen print, “Portret van een zittende man met een lange jas,” dating from around 1859-1866, is quite striking. I’m immediately drawn to the details captured by this early photography technique, but what I'm really curious about is what do you make of its historical and cultural relevance, especially in relation to its materiality? Curator: Well, it's an albumen print. Think about the process. It wasn't simply pointing and shooting. Producing an image involved coating paper with albumen, derived from egg whites, making it sensitive to light. This craft elevates photography beyond mere replication. Look at the tonal range achieved – this was labor, a manipulation of material for artistic expression. Editor: So, the choice of materials and technique are central to understanding it. How did this laborious process impact the final product and reception of photography at the time? Curator: The time-consuming and skilled process implied value. A portrait like this signaled a certain social status, a consumption of both time and resources. Furthermore, the realism achieved through this medium was unprecedented, which had profound consequences in how people thought about representation, reality and its potential commodification. How do you think the choice to depict realism contrasts with previous portraiture techniques? Editor: That's fascinating. Before photography, portraiture was largely the domain of the wealthy. Do you see this photograph as challenging or reinforcing existing class structures, considering its wider availability compared to painted portraits, or is this maybe even just making it more readily available, commodifying art? Curator: It’s both. It democratized image-making to an extent, but the materiality speaks to access and capital. Think about who had the means to commission such a portrait and the access to processing materials? Even within this “realistic” depiction, social hierarchies were being negotiated and reinforced through material choices. The production itself, like the image, is embedded in the material world, laden with social implications. Editor: That really gives me a lot to think about – the material and production process informing the artwork’s social and cultural impact. I never thought of the humble egg playing such an integral role.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.